Are We Choosing “Living Truth” or “Dead Dogma”?

Is censorship justified when a strong consensus considers an opinion erroneous?

Is freedom of speech necessary to promote human progress even when others consider your opinions offensive? What will happen when the norm of Western civilization, tolerance for competing ideas, disappears?

John Stuart Mill had much to say about those questions in “Of the Liberty of Thought and Discussion,” chapter 2 of his 1859 classic On Liberty. While the ranks of illiberal censors grow daily, Mill’s impeccable logic reaches across time to refute arguments censors use to justify their authoritarian actions.

Before we get into the body of Mill’s arguments, an example from his era is instructive.

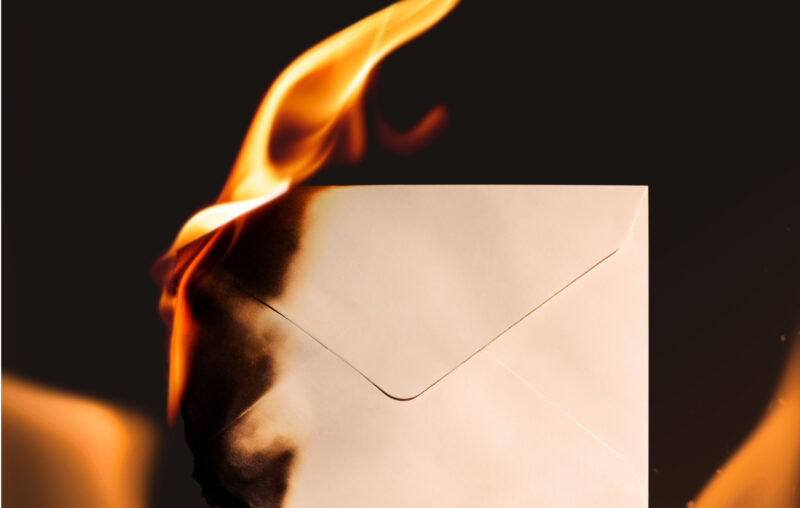

The first direct mail campaign in the United States dates to 1835 when the American Anti-Slavery Society sent sacks of abolitionist mail to Charleston, South Carolina, An angry mob burned the first delivery of that mail after Charleston’s postmaster, Alfred Huger, called it “incendiary” and didn’t deliver it.

Huger asked for instructions from Postmaster General Amos Kendall, who ruled that not delivering the mail for the good of the community was patriotic and trumped federal mail law. If the interest of the community argument for censorship sounds familiar, it should. Google censors make the same argument today.

In a letter to Kendall, President Andrew Jackson argued the abolitionists deserved “to atone for this wicked attempt [to ‘excite’] with their lives.” Huger, Kendall, and President Andrew Jackson were on the wrong side of history and morality, yet they were sure they were right. Today’s authoritarians have expanded the justification for censorship to “mal-information”—”genuine information [that] is shared to cause harm.”

Some might scoff and agree that although yesterday’s censorship was wrong, we have grown wiser, and today’s censorship truly is for the good of the community. Mill observed, “The majority of the eminent men of every past generation held many opinions now known to be erroneous, and did or approved numerous things which no one will now justify.”

Mill was clear that the majority’s opinion may not be wise or moral. He wrote, “Protection… against the tyranny of the magistrate is not enough: there needs protection also against the tyranny of the prevailing opinion and feeling.”

Mill explained why “all silencing of discussion is an assumption of [the] infallibility” of authoritarian censors:

[T]he opinion which it is attempted to suppress by authority may possibly be true. Those who desire to suppress it, of course deny its truth; but they are not infallible…To refuse a hearing to an opinion, because they are sure that it is false, is to assume that their certainty is the same thing as absolute certainty.

Your right to expression doesn’t end even if you are a minority of one. Mill wrote, “If all mankind minus one, were of one opinion, and only one person were of the contrary opinion, mankind would be no more justified in silencing that one person, than he, if he had the power, would be justified in silencing mankind.”

Mill anticipated today’s arguments that censorship is justified because there are “certain beliefs, so useful, not to say indispensable to well-being, that it is as much the duty of governments to uphold those beliefs, as to protect any other of the interests of society.” How often have authorities, experts, and social media companies used that argument during the pandemic to suppress the speech of medical dissidents and dogmatically insist they were the keepers of truth?

It is necessary, Mill advised, that our opinions be “fully, frequently, and fearlessly discussed,” or we will become keepers of “dead dogma” and not explorers of “a living truth.”

Censorship does not protect the public, but it does block challenges to orthodox opinions. When we presume “an opinion to be true” we deter people from seeking the truth or uncovering errors. Mill argued, “Men are not more zealous for truth than they often are for error, and a sufficient application of legal or even of social penalties will generally succeed in stopping the propagation of either.”

Canceling people has far-reaching consequences. Today, out of fear and peer pressure, some professionals clap for policies they secretly question. Mill understood this when he warned: “The greatest harm done is to those who are not heretics, and whose whole mental development is cramped, and their reason cowed, by the fear of heresy.”

Mill asked, “Who can compute what the world loses in the multitude of promising intellects combined with timid characters, who dare not follow out any bold, vigorous, independent train of thought.”

Human flourishing is at stake. Mill warned, “Where there is a tacit convention that principles are not to be disputed; where the discussion of the greatest questions which can occupy humanity is considered to be closed, we cannot hope to find that generally high scale of mental activity which has made some periods of history so remarkable.”

Free expression of ideas is the path to human flourishing. Today’s misplaced certainty is dissolved by progress. Because Mill recognized a person’s capacity as an “intellectual or as a moral being” to learn through “discussion and experience,” he believed errors are correctible in a social process.

Yet, Mill understood “confirmation bias” before psychologists named the human tendency to turn our back on evidence that contradicts our beliefs and opinions. With awareness of this tendency, Mills argued we can counter our bias by exposing our ideas to opposing views.

Notice Mill’s simple safeguard against stubbornly advancing an erroneous opinion: “Complete liberty of contradicting and disproving our opinion, is the very condition which justifies us in assuming its truth for purposes of action; and on no other terms can a being with human faculties have any rational assurance of being right.”

To maintain liberty, each of us is responsible for thinking for ourselves, Mill advised. He wrote, “Truth gains more even by the errors of one who, with due study and preparation, thinks for himself, than by the true opinions of those who only hold them because they do not suffer themselves to think.”

Mill has clear guidelines for becoming a person “deserving of confidence.” We must keep our minds “open to criticism of [our] opinions and conduct.” Mill argued there was no other pathway to wisdom or uncovering errors.

By Mill’s clear standard, authoritarians such as the thin-skinned Dr. Fauci who proclaimed criticism of him is an attack on science, are not to be trusted. Recently, citing his lies and suppression of critics, Matt Taibbi called Fauci “America’s warmup dictator.”

But let’s not let ourselves off the hook. Out of fear, millions worshipped Fauci, thus empowering him. Mill would say you are naïve if you believe errors can be quickly corrected and progress restored even with illiberal censorship. He wrote, “History teems with instances of truth put down by persecution. If not suppressed for ever, it may be thrown back for centuries.”

However, Mill believed truth can never be fully extinguished and will reappear when people regain courage and more liberal attitudes reemerge.

But why wait centuries? The acts of courage needed then will be the same as they are today. Today’s censors, with feet of clay, depend on your acquiescence to having them shape your views. You can withdraw your consent today.