While You Slept, Government Created Internal Passports, Real ID

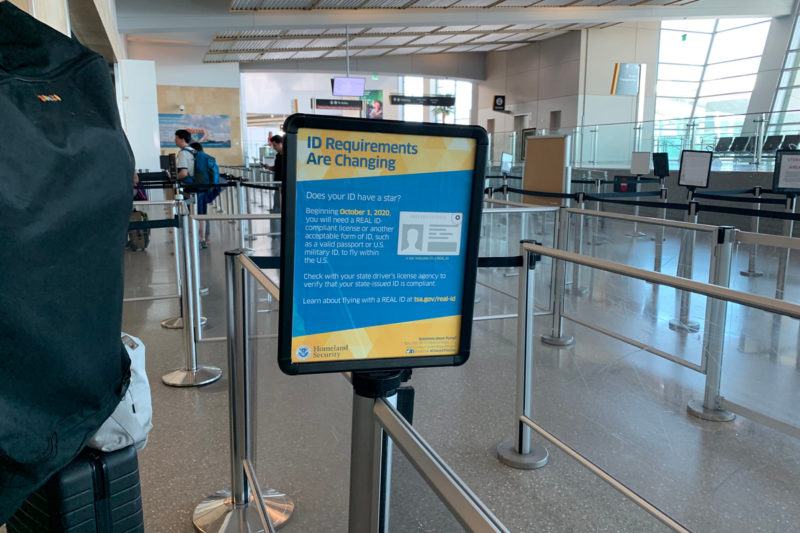

The deadline of yet another, and perhaps the most insidious, element of the post-9/11 initiatives (a partial list of which includes the establishment of the Transportation Security Agency, the Department of Homeland Security, and a never-ending international war against a nebulously-defined, noncorporeal enemy, “terror”) is less than one year from coming to fruition. Beginning no later than October 1, 2020, citizens of all US states and territories will be required to have a Real ID compliant card or US passport to board a commercial plane or enter a Federal government facility. Pundits citing the inevitability of what amounts to a national ID card have, regrettably, been vindicated.

To be sure, some states have resisted, but dependence upon Federal aid and other programs administered from Washington D.C. makes their ultimate surrender and compliance inevitable.

Looking back, Social Security numbers and the cards bearing them broke ground for the path to a national identification system — thank you, Franklin Delano Roosevelt. For decades there have been pointed reminders that the cards were intended to be account numbers and not integrated into a government registry of American citizens.

Repeated efforts, starting in the 1970s, to forge identifiers from the Social Security system have been rebuffed: in 1971, 1973, and 1976. The Reagan Administration indicated its “explicit oppos[tion]” to a national identification system. Both the Clinton healthcare reform plan (1993) and a provision of the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996 requiring Social Security Numbers on driver’s licenses were rejected (the latter in 1999) to some extent upon the basis of tacitly constituting national identifiers for Americans.

There are any number of reasons why the alleged tradeoff between liberty and security that a national ID card represents are being misrepresented. Any system designed, maintained, and run by human beings is ultimately flawed, and in any case corruptible. The existing documents from which the information fed into the Real ID program are eminently vulnerable to forgery. To provide just one example: tens (perhaps hundreds) of thousands of Americans don’t have verifiable, “official” birth certificates.

And people can become radicalized after being issued their Real ID card.

The Real ID also represents the “last mile” in the ability of the state to track individuals in real time. With various electronic, social media, and cellphone tracking measures, there is always a delay; and one can choose not to use social media, not to own a cellphone, and opt into other methods of extricating oneself from the prying eyes of the NSA or other government agencies. But the Real ID — in particular, coupled with biometrics — fulfills Orwellian conceptions of the total surveillance state.

Expect it, over time, to be leveraged against individuals with outstanding traffic tickets, tax disputes, child or spousal support arrears, or behind on loan payments. Access to national parks and historic sites may be tied to it. Recent proposals pushing compulsory voting are a step closer to realization and enforcement with the establishment of a mandatory government ID card. Census data, drug prescriptions, and even library borrowing choices and habits are likely to eventually be linked with personal data associated with the new ID requirement. And if the Real ID is eventually accessible by the private sector, many individuals with innocuously-tainted personal histories may become effectively unemployable.

Indeed: the worst US government infringements upon the life, liberty, and the much referred to “pursuit of happiness” of American citizens over the last two centuries — and mostly within the last two decades — will be vastly easier and more efficient to accomplish with the imposition of a mandatory identification requirement.

I will here make two wagers — both of which I sincerely hope to lose.

First, within five years of the establishment of the Real ID program (October 2020, or whenever it is ultimately established) either a forgery, an enforcement error, corruption, or some combination of those will lead to its sterility in preventing (or commission of) the very forms of terrorism or crime it portends to. Something awful will happen despite (or perhaps employing) the Real ID cards and program. At that point, revocation will not be an option: “reform,” taking the form of increased funding, a larger bureaucracy, and quite possibly greater legal restrictions will instead be piled on.

Second, within ten years of the establishment of the Real ID program it will be required to purchase tickets for and/or board trains and buses that cross state lines. It may also be required at tolls and state crossings in personal vehicles.

I hope both of those predictions are wrong, but as Americans we have been here before. Liberty has yet to win out over increased security despite the ineffectiveness of each and every such tradeoff to date.

Relatedly: where is the media attention? Has a single newspaper headline — let alone a three- or five-minute spot within the incessant droning of the 24/7 media cycle — been dedicated to the impending arrival of an American national ID program? The increasingly partisan, mindless political banter would be tolerable if, occasionally, the media served its role as public tocsin.

The answer to the question regarding what Americans will give up for a measure of security, and in this case a tremendously dubious measure of security, is now clear. Both the Federal requirement that citizens require a passport for domestic travel and the meek acceptance of it by citizens and state officials lead to an irrefutable conclusion: America is not, and hasn’t been for some time, the land of the free. Less is it the home of the brave.