The Covid Crucible

“The books are to remind us what asses and fools we are,” says Faber to Montag in Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451.

The world yet awaits that germinal work of fiction that will encapsulate the horrors of the Covid pandemic. One hopes it is “in press,” about to burst onto the global scene, exposing a dark world if only imperfectly and momentarily, like a bolt of lightning, before arousing our senses with a thunderclap of Truth. One fears, though, that it lay still, deep in the bosom of a Uighur or Mapuche child, still a decade or more from invading the consciousness of English-speaking brains.

I doubt not the power of a Tik-Tok video or tweet or parley to move one’s emotions. Whose eyes have not been moistened by simple stories like this: “Baby shoes for sale, never worn?” Or literally LOL’d at the idiocy of the world exposed by a short video or cartoon strip? But some much longer literary form will be needed to help humanity to feel the Truth about the Covid pandemic. “The tender one who birthed and raised me is gone from Covid …. lockdowns” captures one facet of the story but not enough of its egregious enormity to fill the voids torn in each of our souls.

The world longs for a clarion call for freedom like that of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin, a narrative that spits Truth like venom but ultimately uplifts all who encounter it in any of its forms, which included serialized magazine articles, the famous novel, a scholarly tome defending the authenticity of the novel, sundry songs, and various theater adaptations. (For details, see Robert E. Wright, “Liberty Befits All: Stowe and Uncle Tom’s Cabin” in the Winter 2020/21 issue of The Independent Review.)

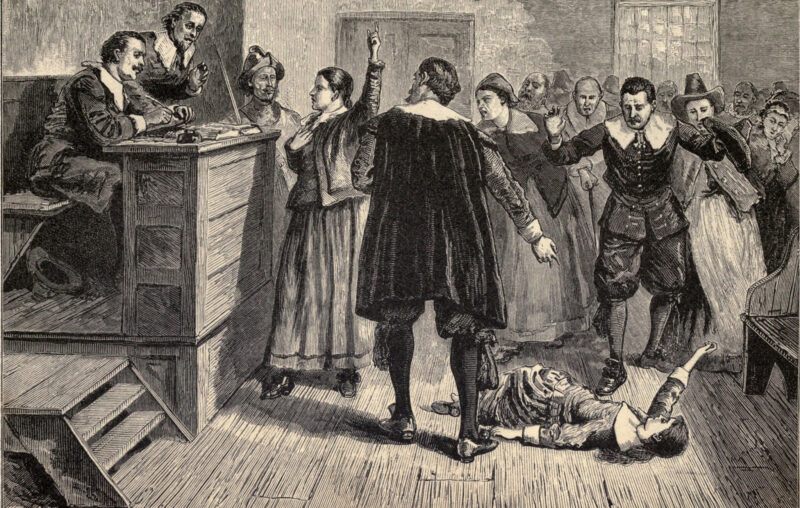

One might interpret Uncle Tom’s Cabin, or any tome about liberation, as a Covid lockdown allegory, but most such exercises soon strain credulity. Arthur Miller’s 1953 play The Crucible, though, might be able to tide us over until something new slips through the fog of viral war and into clear view. I read (and later taught) Miller’s 1949 play Death of a Salesman instead of that other staple of high school literature courses. Recently, though, I viewed the 1996 movie version of The Crucible starring the indomitable Daniel Day-Lewis as John Proctor and a fetching Winona Ryder as his paramour.

Both movie and play more or less accurately depict the 1692-93 Salem Witch Trials, which AIER has already likened to Covid policy responses. Joakim Book, for example, wrote satirically in December of 2020 that “The Salem Witch Trials called and want their rationality back.” Around the same time, Michael Fumento hoped that “we will feel the shame of the Salem witch hunters and all those who aided and abetted them, those in the courts who squirmed and screamed every time a suspect witch was questioned.” A few weeks later, Ethan Yang compared the vicious smearing of Great Barrington Declaration coauthor Sunetra Gupta to the treatment of innocents during the witch trials and the Spanish Inquisition.

Not coincidentally, The Crucible was Miller’s clarion call to end the injustices of the Second Red Scare, the postwar period when Senator Joseph McCarthy (R-WI, 1947-57) and the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC, 1934-75) hunted the “witches” of communism thought to inhabit the highest echelons of American government and culture by besmirching their characters, imprisoning them, and encouraging people to burn their books and blacklist them (just a new word for old timey ostracism). A fearful Columbia Pictures asked Miller to sign an anti-communist declaration before it would release a film version of Death of a Salesman, which many considered an anti-capitalist screed. (Properly understood, it was not. See the discussion in my Mutually Beneficial for details.)

Like accused witch John Proctor, Miller refused to submit to the declaration and, in 1956, was cited for contempt of Congress for not ratting out before HUAC the writers who met at a conference organized by, gasp!, socialists. Unlike Proctor, Miller wrote a play about the situation rather than dangling from the end of a rope but otherwise his life bore a striking similarity to that of the accused witch.

If Miller isn’t your hero yet, the nerdy-looking fellow was Marilyn Monroe’s third husband because, unlike most men, he didn’t immediately hit on her. They had an affair after Monroe divorced Joe DiMaggio (a skilled New York Yankee batsman not to be trifled with) but while Proctor, I mean Miller, was still married. As effectively as the Salem rumor grapevine, the paparazzi ensured that the famous couple couldn’t keep their tryst on the down-low, so Miller divorced his wife and married Monroe, who supported him during his HUAC witch trial. Similar to Ann Putnam in The Crucible, Monroe lost three children (all to miscarriage) before the celebrity couple divorced in 1961.

Those interesting coincidences aside, The Crucible speaks to us today because it dramatizes how private interests can combine with government power to produce widespread paranoid fear of invisible forces and rampant injustice. The details change but the underlying drama remains the same: A wants to destroy B but has insufficient power to do so without C, which can be enticed to aid A by demonizing B by means of D supported with E. The following table summarizes the details for the three episodes considered in this article:

Anatomy of Policy Insanity

| Place/Years | A(ggressors) | B(ad guys, putatively) | C(oercive entity) | D(amnable sanctions) | E(vidence of a hocus pocus variety) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Salem, Mass., 1692-93 | youthful criminals afraid of punishment; religious zealots; greedy landowners | “witches” = weirdos and socially distant people with valuable property | Court of Oyer and Terminer | Excommunication; hanging; ostracizing | spectral evidence of demonic deeds |

| Washington, DC, 1947-58 | American Legion, AWARE, and other conservative anti-communist organizations | “communists” = critics of the status quo; “sexual perverts” = homosexuals | U.S. Congress and FBI | banning; blacklisting; imprisoning | HUAC hearings’ “no smoke without fire”; assumed contagiousness of homosexuality |

| Lockdown states, 2020-ongoing | large corporations and others benefitting from lockdowns, mass vaccinations, etc.; anti-Trumpers; teachers’ unions | “covidiots” = anti lockdowners; Great Barrington Declaration signers; small business owners; religious folk; school children | state and local governments | cancelling; censoring; closing; fining | agent-based epidemiological models; high-cycle PCR tests; retracted scientific articles; inaccurate mass media articles |

Constant repetition of the bizarre and obviously untrue mantra that policymakers are “following the science” and not basing Covid policy on the 21st-century equivalent of spectral evidence suggests that Miller was on to something fundamental. So watch or read The Crucible until the crucible of Covid repression spurs a new literary treatment of the dangers unleashed by that strange brew of populism, private interest, and government power.