Recent Trends and Persistent Disparities in Teenage Labor Force Participation

As summer winds down and kids go back to school, families across America are settling into new routines. “The hardest thing,” as President Biden recently told a group of middle schoolers, “is to come back after three months of not doing any work.” Whether realizing it or not, the President’s remark points to the importance of persistent disparities and recent trends in youth labor markets.

For starters, youth employment (ages 16-24) always peaks around the end of summer, as young workers leave their seasonal and part-time positions to return to high school and college. The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) details this in its monthly youth labor report. So actually, Mr. President, for many students the adjustment isn’t so much about three months of not doing any work. Instead, it’s more like hitting the books after hustling at their part-time jobs all summer.

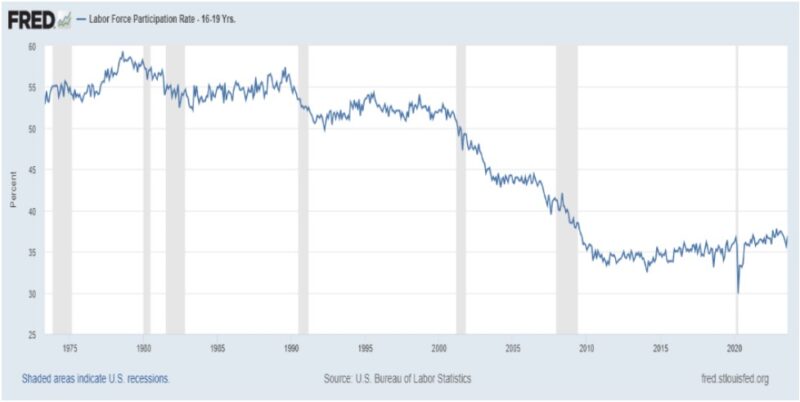

But more important than seasonal fluctuations are long-term trends and recent shocks, especially since early in the COVID pandemic. It used to be that working-age teenagers (those between 16-19 years old) had an average Labor Force Participation rate (LFP) above 50 percent, meaning over half had a job or were looking for work. As the chart below shows, this above 50 percent trend persisted from the early 1970s to the turn of the 21st Century.

Then, starting about the year 2000, the trend shows a remarkable change. Teenage LFP begins to plummet, from over 50 percent in August 1999 to just 35 percent by August 2011, where it then plateaued for nearly a decade. This 2000-2011 decline in teenage LFP was so sharp that some economists argued it was dragging down the labor market as a whole. What could be causing such a remarkable change?

Why Did Teenage LFP Plummet?

Research into this question has pointed to a handful of key factors. One beneficial reason was a dramatic decrease in high school dropout rates during this same time span. A 2015 St. Louis Fed study reports that school attendance among those without a high school diploma went from 38 percent in 1998 all the way up to 60 percent by 2014. With so many young people choosing school attendance, their labor force participation would naturally fall.

Additionally, students are striving to meet higher academic standards. As a 2012 Congressional Research Service (CRS) report states, “Teens appear to face greater academic demands and pressure, which may influence their education and employment choices.” More high school students are spending their time meeting requirements for four-year colleges, and a growing share have been taking AP courses.

College enrollment also plays a factor in teenage LFP, because so many in the youth labor segment are advancing from high school to college age. According to the National Center for Education Statistics, the long-term trend in aggregate college enrollments peaked at about 18 million students in 2010, right at the time when teenage LFP was settling into its 35 percent plateau. Since 2010, aggregate college enrollments have steadily declined, but the decrease has been concentrated on 2-year institutions. Enrollment at 4-year institutions has actually increased slightly during that same time span, by about half a million students since 2010.

More youth are attending school over the summer as well. According to a 2017 BLS report, summer enrollment has steadily increased over the past 50 years, and by 2016 it “was more than 4 times higher than it was in July 1985—42.1 percent versus 10.4 percent.”

Persistent Disparities

Another reason for declining teenage LFP, however, involves the many disadvantages of youth in competitive labor markets. Entry level workers are always the most vulnerable to cycles of unemployment during recessions. As the CRS report says, “Youth have less education and experience relative to older workers. During dips in economic activity, young adults may find it difficult to attain a first job, and … because firms are more likely to lay off those with less seniority and less training.” Looking at the gray shaded areas in the chart above, teenage LFP does experience sharp declines during recessions, without subsequently making up for lost ground.

Unfortunately, an even more troubling reason for declining teenage LFP has been an increase in the population classified as NEETs: Not in Education, Employment or Training. These are young people who are neither investing in their future productivity nor being productive in the present (at least as far as these statistics measure). In 1998, only 8.2 percent of 16–19-year-olds were NEETs, but by 2014 that had climbed to 12.4 percent. Many in this population are sure to account for the decline of enrollment at 2-year institutions.

In addition, racial and sex disparities persist in the labor market. Decomposing the teenage LFP trend by age, race, and sex, the table shows that, in August 2023, black LFP was more than ten percentage points behind white LFP. This gap has persisted over time, with the disparity ranging from about 8 to about 11 percent every year since 2018. Teenage Black unemployment rates had improved to historic lows prior to the pandemic, The CRS report attributes this disparity primarily to differences in educational attainment.

Additionally, it is possible that poor incentives from the social safety net have a negative impact on labor force participation. As the report states, “While youth may want to work, they may choose not to because of the possibility that their families would lose eligibility for assistance programs.” Work in this area by economist Craig Richardson offers insight into “disincentive deserts” and similar problems with public assistance programs.

The table also shows the gender gap in overall LFP, with males persistently about 11 percentage points higher than females. After a brief yet sharp decrease during the pandemic, female and male LFP have slowly recovered, with female having reached it pre-pandemic levels while male remains stubbornly below.

Recent Trends

Almost every imaginable economic indicator was sharply affected by the pandemic. But in just the past year, both college enrollment and teenage LFP show signs of what may be to come. While the pandemic accelerated the post-2010 decline in college enrollment, the most recent spring and fall 2023 numbers indicate college enrollment may be stabilizing, according to the National Clearinghouse Research Center.

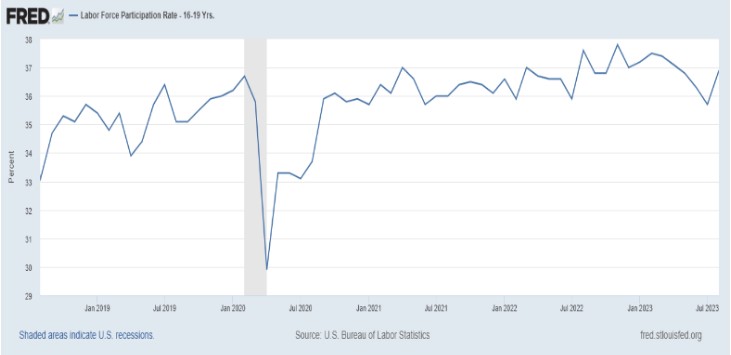

Zooming in on the past five years of teenage LFP data, we can see that the 35 percent plateau in was already being disrupted well before the pandemic. The chart below shows teenage LFP rising from 33 percent in August 2018 all the way up to 36.7 percent in February 2020. After a brief yet sharp dip, teenage LFP rebounded from the pandemic shock to continue its post-2018 trend upward, reaching a 13-year high of 37.8 percent in November 2022.

Outlook

The 2000-2011 decline in teenage LFP is a mixture of both beneficial and adverse trends, which endure while also blending with more recent especially post-pandemic trends. For many if not most American youth, the opportunity cost of supplying labor is simply higher today than it was a generation or two ago. This means that many young people are investing in their future productivity through college attendance rather than working. The benefits of this are on display in various data showing the returns to higher education, such as lower unemployment rates, higher wages, and increased job security.

The costs of higher education, however, have been increasing significantly as well, with college tuition, student loan debt, and government spending on higher education all on the rise. Plus, the returns to a college degree can depend heavily on choice of major, both in lifetime earnings and job satisfaction. A majority of older Millennials report their student debt was not worth it, and up to two-thirds of today’s workers have at least some regrets about their college degrees. Many of the racial and gender disparities in labor markets come down to disparities in education. Finally, the long-term effect of the COVID recession on the labor-market outcomes of young people are still to be realized, compounding these concerns.

Ultimately these aggregate concerns come down to individual decisions of people weighing their own trade-offs and opportunity costs, and choosing a course that they feel is best for them. Market forces, when allowed to work, provide useful information for individuals to navigate tough choices. We saw a lot more teens choosing the workforce starting in 2018 because of greater pay and opportunity, created as older workers were abandoning jobs in sectors like food service, and as firms were “rediscovering young people as a source of labor.” Policymakers, perhaps starting with the President, could benefit from more of this perspective.