It’s Not Capitalism Bringing Us Deaths of Despair

If your only tool is a hammer, everything looks like a nail.

With Deaths of Despair, the Princeton professors Anne Case and Angus Deaton have launched a competing strategy: if your arch nemesis is American healthcare, every social ill looks like its fault.

To recap: deaths of despair is the uncannily catchy label that the authors used to describe deaths from suicides, drug overdoses and liver cirrhosis, all of which are clear indications of people who fail to find meaning in life; in Case and Deaton’s words: “People kill themselves when life no longer seems worth living, when it seems better to die than to stay alive.”

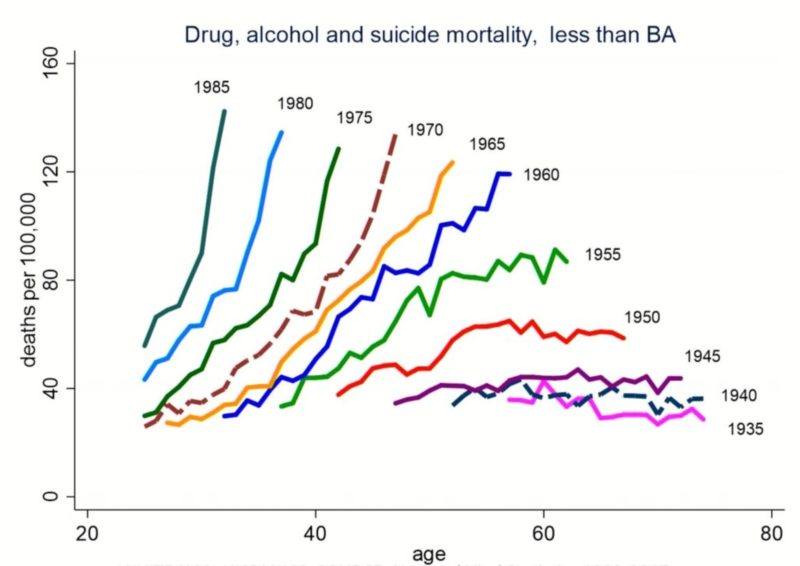

While I’m mostly upset with Case and Deaton’s under-analyzed and hand-waving arguments for why U.S. healthcare is to blame, I’m impressed and dazzled by their descriptive case. They masterfully dismantle simple explanations that don’t fit the facts (income, unemployment, obesity, inequality, the Great Recession) and bring forth the relevant characteristics of these deaths: mostly White, mid-life Americans with less than a college degree. Other ethnicities seem so far to have avoided them, and those having finished college could perhaps be excused for not having noticed this longstanding trend as it hasn’t touched them. Cohort by cohort as those born in 1955 were turning 40 (mid-1990s) the mortality from deaths of despair grows steeper; the even higher rate of death faced by those born in 1955 as they approached 60 is surpassed by those born 1985 before the age of 30:

The steady growth of these deaths since the 1990s have escaped simple stories and so provided fertile soil for our astute professors into which to weave their nemesis.

As few other countries have seen a similar explosion of deaths of despair, the authors convincingly argue that this “American experience needs an American explanation.” After vigorously and at length having accounted for the hundreds of thousands of deaths among predominantly working-class white America, where do Case and Deaton place the blame?

Primarily among the healthcare industry. But in fairness, a little bit all over the place: Lawyers; rent-seeking corporations and their outsourcing and lobbying; a failed (American only?) capitalism that no longer works for the very poor whose living standards it pretends to help; definitely the collapse of unions and the monopsonic employers they combated; greedy bankers and real estate moguls; and a government complicit in all. With such wide nets, everyone seems to have caught some blame.

How to Make HealthCare a Villain

Many people, rightly or wrong, detest American healthcare and Case and Deaton have tapped into this anger. Shown repeatedly that government-provided health insurance doesn’t have the kind of revolutionary effects that its proponents usually ascribe to them, Case and Deaton had to find another route unique to America through which to blame American healthcare. What then, if government health insurance doesn’t help and the usual suspects of income, poverty, unemployment and health don’t work?

Competent scientists would retreat, re-evaluate their priors and admit that reality is more complicated than the single-minded, preconceived notions would support. Having no patience with such intellectual constraints of decency, Case and Deaton rather doubled down and forced their unruly pieces into place through two arguments that remain largely unproven:

- A bloated healthcare expenditure can only be said to harm the white working class into killing themselves if it materially reduced their incomes. Mis-calculated wage stagnation theses aside, Case and Deaton submit that benefits from employer-provided healthcare coverage has zero value. Thus, they managed to show total worker compensation falling and thus created plausible grounds for arguing that all America received was upward redistribution to medical cronies at the expense of the wage-stagnated working poor.

- Downplay the competing explanations for why (rural) white America is suffering: wave away community, values and industriousness; reject globalization and automation; posit “America’s unique history of race” – always a nice deux ex machina to invoke – and finally accuse “its limited welfare provision.”

Voila! We proved what we set out to prove by assuming the conclusion. Very elegant. Aristotle would have a thing or two to say about this.

Under the proficient hands of Case and Deaton, deaths of despair become extreme indicators for a corrupt healthcare system gone awry. Their primary channel – opioids – is at least believable, while their secondary channel – wages – required some tendentious statistical engineering.

The opioid epidemic is a thankful smoking gun as the drugs are, at least initially, supplied and prescribed by the very medical community that Case and Deaton wish to blame. Besides, it is certainly true that doctors have prescribed a lot of morphine and fentanyl – whether through misplaced trust in drugs as a catch-all medical solution or through financial incentives from Big Pharma, matters little. Writing in The New Yorker, Atul Gawande admits that “we physicians, to our lasting shame, gave out the drugs like lollipops.”

Where that plausible explanation falls apart is its strangely distributed harm. If unscrupulous Big Pharma would step over overdosed corpses in their quest for profits, how come their unscrupulousness stopped along racial and educational lines? Do healthcare’s malignant effects on pay and communities somehow restrict itself to working class Whites only? Maybe doctors only treated white people’s pain?

Alternatively, are Blacks and Hispanics less likely to visit over-prescribing doctors or are doctors – selectively, and as it turns out fortuitously – deciding not to prescribe non-whites the very opioid drugs Case and Deaton most rally against?

While entirely leaving these problems unexplored, the authors do admit that one predicament for which opioid painkillers was prescribed was arthritis, a disease largely associated with age. As we all age and arthritis is fairly evenly spread among the population, it’s strange that only less-educated whites fall prey to the opioids. Never mind; it must still be healthcare’s fault.

Even though I’m happy to concede blame to Big Pharma or broken incentive structures in American healthcare – areas for which I am not qualified to comment – that explanation fits very poorly within their overall story (or the ad hoc premises we need to invoke to make it work are unbelievable).

The wage-channel of their story is similarly dubious. A large chunk of their descriptive story is to show that deaths of despair are not a result of material deprivation: Blacks are proportionately much more likely to be poor than the very Whites who are killing themselves in troves, yet have largely escaped both the opioid epidemic and deaths of despair more generally. Case and Deaton repeatedly stress that it’s not absolute levels of poverty that matter nor material deprivation, but rather the trend and reasonable outlook.

But if material deprivation is not a believable channel, how come the artificially low (negative) wage growths that you engineered by exempting the value of healthcare coverage is a valid channel? If the “high wages and good jobs” you associate with manufacturing ages past are no longer available for the less-educated American whites, how can that be an indictment of healthcare that – quite possibly – raised the cost of hiring workers, but not an indictment of automation and globalization that comparatively raised the cost of American industrial workers even more?

Dissonances never bothers those with an axe to grind.

Case and Deaton’s book and intricate discussions are filled with these incoherencies. The lobbying argument is a case in point. After spending a few pages outlining how much big corporations spend on each representative and senator and by how much they outspend unions they regain some long-forgotten nuance: lobbying “is not a machine whereby firms and individuals with deep pockets can write their own legislation […] there is too much competition and too many lobbyists on all sides of the big issues.” Therefore, “it has not rigged the system so that it only works for the paymasters.” How, then, is lobbying partly to blame for the disaster the authors spend two-thirds of the book exploring? It is unclear why this is included in the book unless the authors mean to imply that lobbying has at least somewhat “rigged the system”?

At one point, unable to avoid accusing bankers, they hold as a material harm to the poor that lots of mortgages leading up to the Great Recession “shouldn’t have been sold” – but don’t consider its natural flipside: the poor who couldn’t service those mortgages shouldn’t have had access to the superior housing they did either.

Presumably, that wouldn’t go down well with their mostly anti-capitalist audience, an audience they frequently cater to. Already on the first page they give in to populist language: capitalism doesn’t have to be abolished, they say modestly, but “it should be redirected to work in the public interest.” As if capitalism isn’t already working in the public interest and as if there was somebody capable of steering “it” onto a different, more enlightened path.

One fundamental topic I struggle with throughout the book is how the quality and structure of a country’s healthcare system, laying downstream from its economy and its individuals’ behavior, can be to blame for outcomes of that population’s behavior. Usually, it’s what we do economically and socially that lands us in hospitals rather than what hospitals do that change the way we live our lives. Mid-life whites (and younger and younger cohorts) are dying, as Case and Deaton superbly lay out, after losing faith in the prospect of their own lives. That prospect lays mostly upstream from healthcare providers, and it’s hard to see how a possibly corrupt, negligent or broken healthcare system sapped the white working class of their life prospects.

Somehow the authors must find a causal mechanism that works backwards. The addictive nature of opioids too liberally prescribed would be one such channel, but it leaves unanswered why the mid-life whites were in pain in the first place, requiring them to visit doctors to prescribe them the drugs. We can readily see how sociological explanations of community fits into this story, or the frequent economic story of globalization and automation outcompeting unskilled labor. It’s not clear how a “wasteful” healthcare sector – apart from the unbelievable wage channel discussed above – does that.

What Happened to the other suppliers?

There is at least one more thing in their story that is particularly odd: the other suppliers.

We can readily see how overdoses from addictive drugs oversubscribed by a lenient healthcare industry would implicate that industry. They are, after all, the producers and dispensers of the means with which hundreds of thousands of Americans – willingly or not – ended their lives. But as three-quarters of suicides are done with firearms or through suffocation, I wonder where are the wide-ranging indictments, bordering on conspiracy, of rope manufacturers, of car exhaust makers, of producers or dealers of firearms? Or the alcohol industry that supplies the numbing substance that amounts for a quarter of the deaths of despair?

Don’t get me wrong: I don’t have a problem with these industries. I do have a problem with authors applying logic haphazardly and selectively blaming industries they don’t like. From Case and Deaton, we see not a word about these industries. That suggests to me that the authors are on a one-sided quest, rather than dispassionately trying to understand the deaths of despair that has rampaged communities of working-class Americans.

For a story of long-term decaying communities, loss of status and material deprivations for the white working class may have eroded social bonds. It’s a story that we’ve grown accustomed to with terms like the China Shock and the Rust Belt; the social capital from Robert Putnam’s Bowling Alone; and other popular explanations for the election of Trump and the Brexit that we didn’t see coming.

In recent years, authors left and right have tried to draw our attention towards the ills of the white working class, the losers of globalization: from Paul Collier‘s The Future of Capitalism to Raghuram Rajan‘s The Third Pillar, to Charles Murray‘s Coming Apart and David Goodhart‘s The Road to Somewhere. (They refer to these and many other Big Picture publications of how capitalism has failed as “a recent flood of books”). The field that Case and Deaton ventured into had gotten crowded.

Perhaps they merely wanted a unique twist – and went with blaming Big Pharma. They had a thesis – American healthcare is to blame for everything – and investigated deaths of despair as a fruitful candidate.

Answering why is always harder than what, an old intellectual conclusion that Case and Deaton’s interesting book supports. Their description of mortality and morbidity facing primarily mid-life whites without education in America’s rural hinterland is superb, their attention to nuance and detail masterful. That’s where the praise should end.

When the pieces of the puzzle no longer fit, they resorted to vague “conflicts of power,” mysterious powers of lobbying, and lack of reliable safety nets. These phenomena are arcane enough and universal enough to at least be plausible candidates for having created (or exaggerated) the epidemic that is deaths of despair.

At the end of the day, thus, Case and Deaton bring a new story to the table, a story they are unable to explain unless resorting to conspiracies and anti-capitalist mantras. Same old, same old.

The world is complicated and statistically tricky, while ideology is an inflexible dogma (“a menace,” writes Case and Deaton’s intellectual brethren Paul Collier). Nuance brings out these authors’ best, despite their guttural contempt for America’s healthcare.

Case and Deaton’s descriptive work is great; their explanatory work, to put it mildly, does not impress.