The Trade War’s New Level of Bizarre

It’s been another wild two weeks in the world of tariffs and trade. It began with a tariff threat from the U.S. president that seemed to come out of the blue. He threatened a 5 percent tariff on imports from Mexico — which might be increased to 25 percent over time — as a way of dealing with a migrant crisis at the Southern border.

It ended with a series of tweets in which the president took credit for a new policy on the part of Mexico: the country would crack down on migration from its Southern border and also buy agricultural products from the U.S. as a way of dealing with the supposed problem of the U.S. trade deficit.

There will be no new tariffs against Mexico, for now. However, the hiatus might only be temporary. “The tariff threat is not gone,” one Trump administration official (who is probably Peter Navarro) told the New York Times. “It’s suspended.”

And that raises a serious problem for businesses on both sides of the border. Can or should they continue to make deals and investments, or should they look for other markets? This regime uncertainty can be as costly as tariffs themselves.

Even stranger, there was no relationship between the stated problem (a migrant crisis and a drug problem in Mexico) and the proposed solution (taxing Americans). Even more bizarre, taxing Americans for buying goods will harm economic health in both countries, which will likely intensify problems at the border.

In any case, at the height of the threat, it seemed impossible to find anyone not directly employed to speak for Trump who is willing to make a case for these tariffs. Republicans in Congress pushed back for obvious reasons: this can only harm businesses and consumers. And it wasn’t only the political class. Every important voice in financial markets and banking spoke out with unusual candor about how terrible this tax would be.

Even stranger, we’ve since learned that all the essentials of the U.S.-Mexico deal had already been hammered out between December 2018 and March 2019. Moreover, the U.S. had only recently put together a new version of Nafta. The sudden imposition of new taxes on Americans would violate every bit of the spirit of the deal and raise fundamental questions about whether the U.S. can be trusted in any of these trade negotiations.

What Deal?

There’s also the matter of this bizarre tweet: “MEXICO HAS AGREED TO IMMEDIATELY BEGIN BUYING LARGE QUANTITIES OF AGRICULTURAL PRODUCT FROM OUR GREAT PATRIOT FARMERS!”

Problem 1: the communique from the U.S. and Mexico makes no mention of such new promised purchases. No one on either side of the negotiators had ever heard of such a thing. Bloomberg reports that “increasing Mexico’s purchases from the U.S. wasn’t discussed during the three days of talks in Washington that led up to Friday’s agreement, said the three people with knowledge of the deliberations who weren’t authorized to speak publicly.”

In other words, so far as anyone can tell, the claim that more purchases is part of the deal seems to be made up out of whole cloth, though no one was willing to go on record in saying that. There appears to be no change to the patterns of U.S./Mexico trade, which is actually much larger today than ever.

Problem 2: U.S. agricultural exports to Mexico are already high. They have been growing for decades.

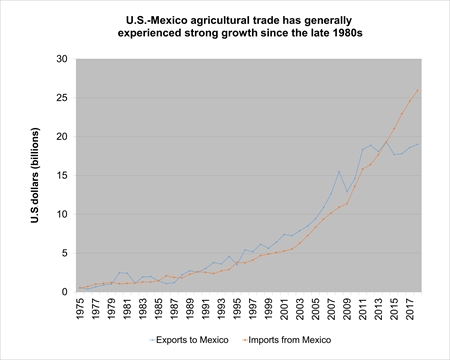

“In 2018, Mexico accounted for 13.6 percent of U.S. agricultural exports and 20.1 percent of U.S. agricultural imports,” reports the USDA. “Between 1993 (the year before NAFTA’s implementation) and 2018, U.S. agricultural exports to Mexico expanded at a compound annual rate of 6.9 percent, while agricultural imports from Mexico grew at a rate of 9.4 percent.”

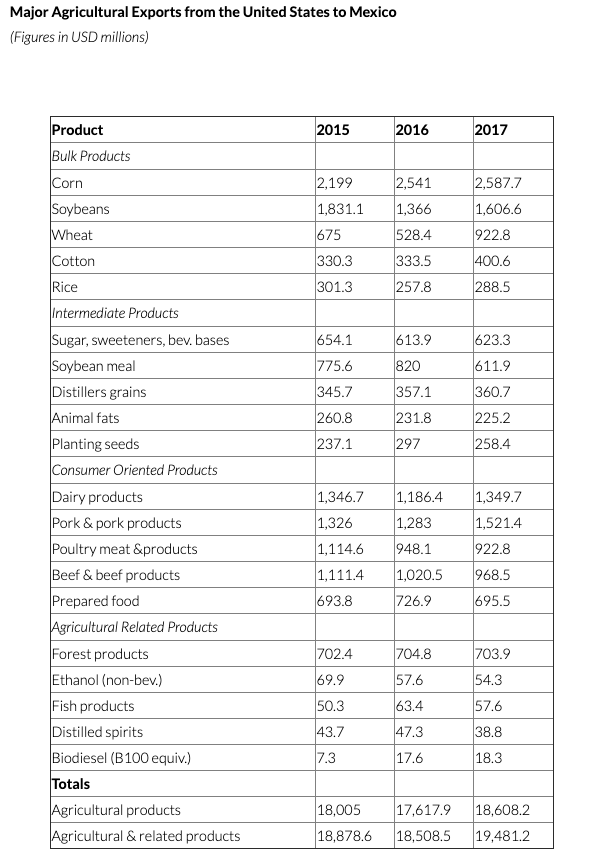

The specific products exported track U.S. agricultural subsidies:

What’s happening here is pretty clear. For seven years, bulk agricultural exports to Mexico have been increasing. At the same time, the world market prices for all these have fallen ever further due to vast oversupply. Thus, the total value of U.S. agricultural exports to Mexico has remained flat.

The U.S. massively subsidizes production of corn, soybeans, and wheat along with their by-products, thus generating vast overproduction and driving down the price and squeezing the financials of American “patriot” farmers. The subsidies, then, are having a reverse effect. Intended to help farmers, they are making them ever more dependent on Washington’s largess and the use of government power in seeking to find purchasers for them. The trade wars have been particularly devastating because U.S. farmers have lost access to foreign markets due to retaliatory measures.

Trump’s tweet might have been wishful thinking, but it shows where all of this is headed: the U.S. will use gunboat diplomacy via protectionist threats as a way of forcing foreign purchases of its vastly overproduced grains. It’s one way in which domestic socialism feeds into a foreign policy of trade imperialism.

The Trade Deficit

Underlying this whole financial and political problem is deep intellectual confusion over trade deficits, a subject over which Trump and his top trade advisers are obsessed. Look at the balance-of-trade data as it pertains to Mexico.

U.S. goods and services trade with Mexico totaled an estimated $671.0 billion in 2018. Exports were $299.1 billion; imports were $371.9 billion. The U.S. goods and services trade deficit with Mexico was $72.7 billion in 2018.

A 5 percent tariff, all else equal, will take from Americans $18.1 billion, or $141 per American household. Increasing that tariff to 25 percent will take from Americans $92.5 billion, or $725 per household. The magic number for Trump is $72.7 billion. So long as this number is floating out there, Trump will seek new ways to punish Americans for buying goods marked with Mexico as the country of origin.

Economists have known for centuries that balance-of-trade numbers have no serious economic significance. You can calculate how much you buy from Burger King against how much Burger King buys from you, but it means nothing for how much enjoyment you get from eating a burger. There are gains from trade regardless.

However, if you are somehow deeply confused and come to believe that these trade data are somehow analogous to the balance sheet of a firm, you could easily render deficits as losses and surpluses as profits. If you are the head of state and imagine yourself to be the CEO of a country, your job then becomes to make sure that you run trade surpluses with the world.

Now, to be sure, most heads of state do not think this way. But there is a special type of businessman/politician who is tempted in this direction.

Frederic Bastiat wrote about this problem in the 19th century. The fundamental fallacy is to “compare the books of the counting-house with the books of the Customhouse.” In this view, so long as imports exceed exports, we are on the road to ruin. The ever-clever Bastiat suggested a remedy for France: “France has a very simple means of doubling her capital at any moment. It is enough to pass them through the Customhouse, and then pitch them into the sea. In this case the exports will represent the amount of her capital, the imports will be nil, and even impossible, and we shall gain all that the sea swallows up.”

We can even go further. If the Trump administration is truly dedicated to balancing trade with Mexico and even logging an accounting profit, however fictitious and irrelevant, we could fill the sea in two directions: the U.S. could pitch all Mexican imports into the sea, and Mexico could do the same with agricultural products exported from the U.S. The seas would fill up, and everyone could get rich!

You know what’s rather remarkable about this silly story? It’s actually coming true. In April 2019, the U.S. trade deficit with the world actually tumbled because both imports and exports took a dramatic fall. The narrowing of the deficit came about because imports fell to a greater extent, which is to say that American businesses and consumers benefited ever less from foreign productivity.

source: tradingeconomics.com

This is nothing to cheer! The last time the U.S. recorded a trade surplus with the world was 1975 — a year that no one remembers as the height of American prosperity.

The absurdities of this 18-month-old trade war are a case study in how one bad policy feeds another and eventually ends badly for everyone. So far, this war has produced disrupted supply chains, higher costs for business and consumers, new financial pressures that have resulted in closings and job losses, vast costs in farmer-bailout funds, a loss of U.S. negotiating credibility, a coalescing of new trading zones that are challenging U.S. dollar supremacy, pressure on the Fed to ease money as a way of mitigating slower growth, and, now, no shortage of fibs to cover up the failures.

The Trump administration pulled back from the brink of disaster in trade relations with Mexico — but there is reason to doubt that this unusual display of good sense indicates a change in intellectual orientation, much less a lasting shift in policy. The man-made trade mess of the last year and a half is likely to get more bizarre before it gets better.

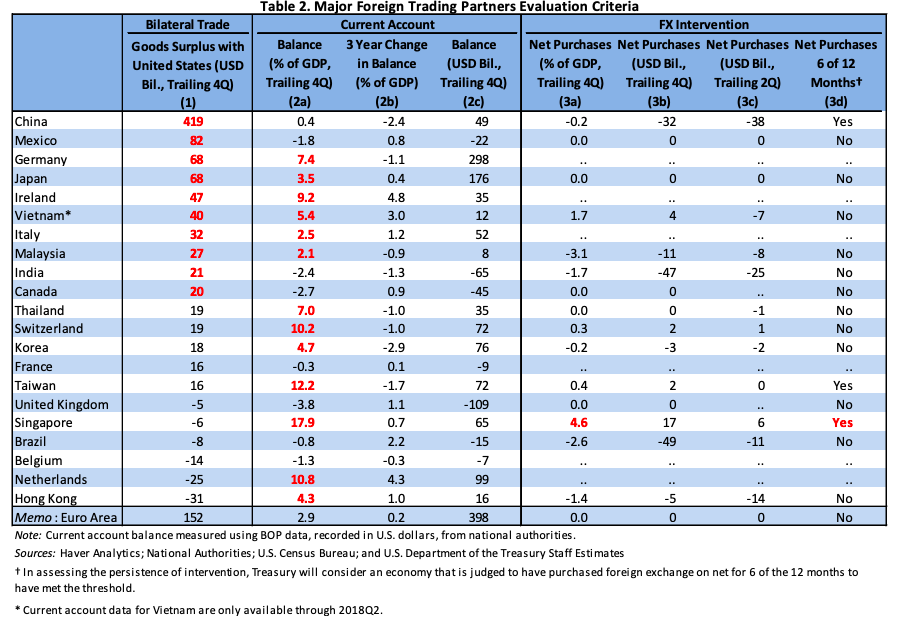

How bad can it get it? Don’t take my word for it. Browse the Trump administration’s own May 2019 report that includes a complete hitlist of all countries with a trade surplus with the U.S. This whole document reads like a caricature of childish economic fallacies. The real world consequences could be devastating, once the trade wars with Ireland, Vietnam, Italy, and Malaysia commence. If anyone thinks Mexico is off the hook, he has failed to comprehend the fullness of the economic ignorance of this administration.

Behold the blueprint: