The Real Problem Is the Politicization of Everything

The Covington Catholic High School fiasco that has developed over the last weeks has shown more than ever why many are skeptical about the media these days. Facts and context — the reality on the ground — were put in the background in favor of a fable that confirmed a political allegory.

What is most shocking is that in today’s world, this is not an exception anymore. Much blame may be shifted to social media as a phenomenon that makes people feel safe in the anonymity of the online world and thus less inhibited than they would otherwise be. Still, the Covington Catholic saga is simply a symptom of a much bigger problem: the politicization of society — or, indeed, everything in life.

Needless to say, politicization is not new. But it feels as though, in today’s dramatically polarized climate, it is more extreme than in decades before. The Gillette ad, perhaps the only other “news story” that has garnered as much attention as Covington Catholic this year, is a prime example: regardless of what one thinks of it in the end, the question needs to be put forward why Gillette even thought it necessary to make a political statement in a commercial for razors. One needs to ask, to mention another example, why Ben & Jerry’s ever felt the need to launch a new ice cream named for “the Resistance.”

Consumed and Blinded

These days, it seems almost an impossibility to meet family and loved ones and not discuss Trump, Brexit, or the European elections. It seems unavoidable to be quickly judged by other humans not by your character but your political views. Everyone who is generally a Trump supporter has to be a fascist with whom one cannot interact anymore. Everyone who is generally a Democrat has to be a socialist or member of the elite with whom one cannot interact anymore.

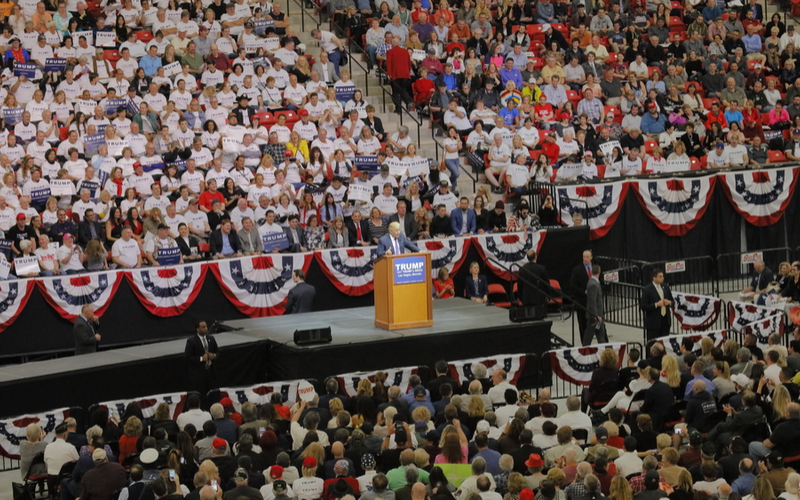

Everyone is defined merely by one’s politics, by one’s party allegiance — whether one voted Republican or Democrat or Libertarian in the last election, or whether one was in favor of Brexit. Every issue is framed in these terms. A case in point for this is certainly also the Covington Catholic boys, who, for some reason, wore MAGA hats at a rally that was supposedly about preserving life. Again, a rally on principle developed into the sanctification of a great leader.

Why We Care

All of this is not to say that politics should not be important. Politics influences all of our lives in innumerable ways day in, day out. And as Micah Watson notes in a must-read essay, it is quite natural to be worried when your grandpa is voting Trump or your niece is feeling the Bern. “True friendship,” Watson writes, depends “on a shared understanding of what is good.” And

when our neighbors endorse a significantly different political vision than we do, we intuitively sense that this is more than a mere disagreement about how to solve a problem, like two college roommates on a road trip bickering over the best way to get to spring break. This is a radical (to the root) disagreement about what counts as a problem in the first place.

Thus, “we should feel some sense of alienation when our friends and our neighbors endorse a position we find wrong or even abhorrent.”

But when people threaten children, call their relatives at the Thanksgiving table racist white supremacists or naïve libs who need to be owned, and when someone like Hillary Clinton goes so far as to say that Democrats “cannot be civil” anymore with Republicans, it may have gone too far. As Karl Salzmann writes, when the occupant of the White House becomes more central to the way we treat people than our views on “morality, virtue, and imagination,” this is a problem. Politics, then, may have become too important indeed.

This is a problem the great C.S. Lewis also saw when he mused that we should focus on “a household laughing together over a meal, or two friends talking over a pint of beer, or a man alone reading a book that interests him.” Meanwhile, “economies, politics, law, armies, and institutions, save insofar as they prolong and multiply such scenes, are a mere ploughing the sand and sowing the ocean, a meaningless vanity and vexation of the spirit. Collective activities are, of course, necessary, but this is the end to which they are necessary.”

So what is a possible way out of this conundrum? A multitude of proposals have been made to detoxicate today’s climate, and it would frankly be pretentious for me to claim to know the solution. Nonetheless, one surefire way, as friends of liberty will quickly point out, is to get politics out of our lives. As Kristian Niemietz notes, “The most obvious antidote to a dysfunctional, adversarial political culture is just to do less politics.”

What does that require? It necessitates a dramatic reduction in the size and scope of the state, the building of a wall between the state (so long as it exists) and the rest of our lives, and the restoration of the conviction that society works best when it is left alone. In other words, we need desperately to resurrect the vision of classical liberalism and draw lessons from its modern heirs in the libertarian tradition.

As John Stuart Mill summarized in 1869: “The modern conviction, the fruit of a thousand years of experience, is, that things in which the individual is the person directly interested, never go right but as they are left to his own discretion; and that any regulation of them by authority, except to protect the rights of others, is sure to be mischievous.”

While on the market and in radically decentralized systems, disagreements and polarization are not a problem, centralized political decision-making has in its nature that only one view can prevail. Suddenly, who is in the White House or whether regulation X or Y is passed does matter a great deal, and those with a different opinion than you on it may seem like actual enemies. Within voluntary settings, one can live with people that one disagrees with. All parties curate a way of life that works while living in peace with others.

To regain civility in human interactions and finally treat other human beings as human beings again, we would do well to get politics out of human affairs.