The Brutalization of College Students During Lockdowns

On March 10, 2020 at 7:16 p.m. the University of Dayton tweeted that all dormitories on campus would be closed less than 24 hours later in order to protect “the health and safety of our campus community.” It was one of hundreds of colleges and universities that rushed to clear out its campus in mid-March over fears of an impending coronavirus outbreak.

Most of these decisions were announced at a moment’s notice, leaving only a matter of days or hours for students to comply and make last-minute travel and housing arrangements in the face of impending eviction.

Dayton’s order proved particularly egregious. The college displayed little concern for the health and safety of its community members who had no mode of transportation or financial means to leave the campus with virtually zero notice. Its 11,271 student population had to vacate immediately. When a group of students took to the streets around campus to protest the hasty and chaotic decision, they found themselves accosted with pepper spray pellets by police officers who broke up the protest at 2:15AM.

Now imagine if an apartment owner or rental house landlord behaved similarly toward paying residents. They would be denounced as slumlords for throwing people out into the street without recourse. They might also run afoul of Ohio eviction law, which states that a landlord must issue a minimum three-day notice prior to evicting tenants. Similar laws exist in almost every single state. Yet when American higher ed cleared out its campus residences last spring, it did so under the moralizing language of “acting responsibly” to contain the virus.

Similar instances of college students being hung out to dry by the hasty decisions of college administrators occurred all across the United States in the week leading up to the lockdowns. Georgetown professor Bryan Alexander estimated upwards of 14 million students were affected by the decisions. USA Today issued a headline as early as March 11, 2020 stating “[m]ore than 100 colleges cancel in-person classes and move online.” In explaining to NPR the rapid adoption of social-distancing measures by American universities, Alexander noted that “[h]igher education has a very strong herd mentality.”

While acting out of an abundance of caution for the sake of public health, institutions of higher learning paid little attention to the unintended consequences of their actions. In addition to causing chaos for students, the abrupt dormitory closures likely had the opposite effect of their expressed intentions. Despite these measures being adopted to stem the pandemic spread, the coronavirus was already here and already widely prevalent in locales such as New York City and Boston by mid-March.

Hastily shutting down campuses in these areas therefore likely increased the spread of the virus as hundreds of thousands of out-of-state students dispersed from the outbreak hotspots of the Northeast to homes with elderly family members and other locales across the country. While we will likely never know exactly how many of these students were infected at the time, it’s a probabilistic certainty that some of them carried the virus with them.

Digging into the Data

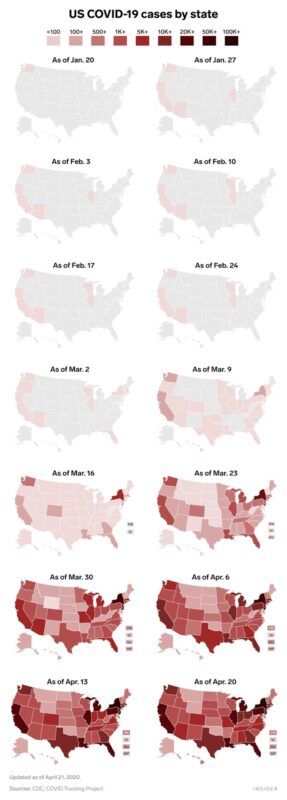

The geographical concentration of colleges indicate the impact of higher ed closure as a superspreader event. Of approximately 4,324 colleges and universities in the United States, 524 are located in the states of New York, New Jersey, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut – the regional focus of the first wave. If we add other early hotspot states of Pennsylvania and Michigan, we get 879 institutions, or roughly 20% of all colleges and universities in the United States.

In these same states there were roughly 3.7 million students enrolled in institutions at the time of the Covid-19 outbreak. Extrapolating from 2017 data on the total fall enrollment in degree-granting postsecondary institutions from the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), as well as from 2018 data on the percent of out-of-state first-time degree-seeking undergraduate students from the NCES, we estimate that over 900,000 students in the northeastern region (plus Pennsylvania and Michigan) permanently resided in other jurisdictions.

The data from the NCES on total fall enrollment includes all postsecondary institutions, not just undergraduate programs, whereas their data on out-of-state students limits itself to describing only undergraduate enrollment. Our analysis assumes that the number of students in Title IX institutions is relatively stable between 2017 and 2020; that out-of-state attendance at Title IX institutions is roughly equivalent between undergraduate and graduate schools; and that out-of-state enrollment patterns for undergraduate students did not vary significantly between 2018 and 2020.

These methodological limitations fully acknowledged, it is plausible that nearly one million out-of-state undergraduate and graduate students from colleges located in pandemic hotspot states were dispersed wide and far across the United States, if not the world, in the crucial early days of the Covid-19 outbreak. We do not know where exactly these students went, beyond simply noting the number. This concern went virtually unconsidered by the media, which busied itself devoting enormous amounts of airtime to scrutinizing much smaller geographic “superspreader” events. In fact, almost no efforts were made to contact trace or even raise awareness about potential virus spread from the sudden displacements caused by hastily announced dorm closures and campus evictions.

By dispersing on-campus residents, not only did colleges and universities potentially spread the virus to other regions of the country, but it also triggered a secondary consequence of removing young people from a residential environment composed mainly of their age-group peers and returning them to multi-generational households with parents, grandparents, and other elderly relatives. According to CDC data, Covid-19 displays a pronounced age gradient in its pattern of attack: younger people (including the college-age demographic) have comparatively low rates of severe Covid, while their older family members face much greater risks of both hospitalization and death.

Unfortunately, testing capacity was extremely sparse in the early stages of the pandemic, leading to limited data on actual case numbers from March. This was compounded by the Trump administration’s rejection of WHO-approved coronavirus tests, in favour of producing American ones. Moreover, due to the limited testing availability, the CDC issued guidelines encouraging only the following, narrowly-defined subpopulations to get tested:

“Hospitalized patients who have signs and symptoms compatible with COVID-19… Other symptomatic individuals, such as older adults and individuals with chronic medical conditions and/or an immunocompromised state that may put them at higher risk for poor outcomes… any person, including healthcare personnel, who within 14 days of symptom onset had close contact with a suspected or laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 patient, or who had a history of travel from affected geographic areas.”

The timing of the spring 2020 peak in US Covid-19 deaths coincided almost exactly with the one month mark following students’ unceremonious departure from campus. Considering the knee-jerk, hasty, “herd-mentality” decision-making of higher education at this time, it would seem only reasonable to scrutinize whether their policies, by dispersing student populations across the country, unintentionally exacerbated the outbreak in the general population.

Washington University in St. Louis was one of the first major institutions of higher education to cancel in-person operations on March 7th. On March 11th, the school instructed its students enjoying spring break to not return to campus as the remainder of their semester would take place online. Students still on campus were granted four days to vacate the premises, writing: “Any students who remained in university housing over spring break were told to leave residence halls no later than March 15.”

Between March 10th and March 15th, a litany of other major institutions followed suit, including virtually all of the major universities in the Northeast: Harvard, Boston University, MIT, Boston College, and Tufts in Massachusetts; Brown and RISD in Rhode Island; Yale in Connecticut; Columbia and Barnard, Cornell, the City University of New York, and NYU in New York; Princeton, Rutgers, and Drew University in New Jersey; Penn State, the University of Pittsburgh, and West Chester University in Pennsylvania; and the University of Michigan and Wayne State University in Michigan.

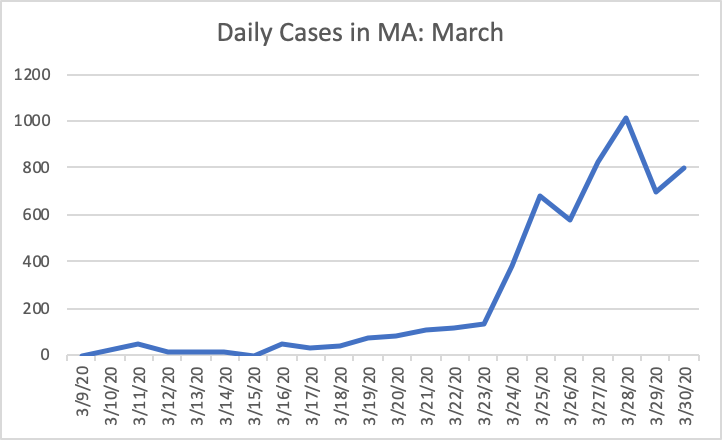

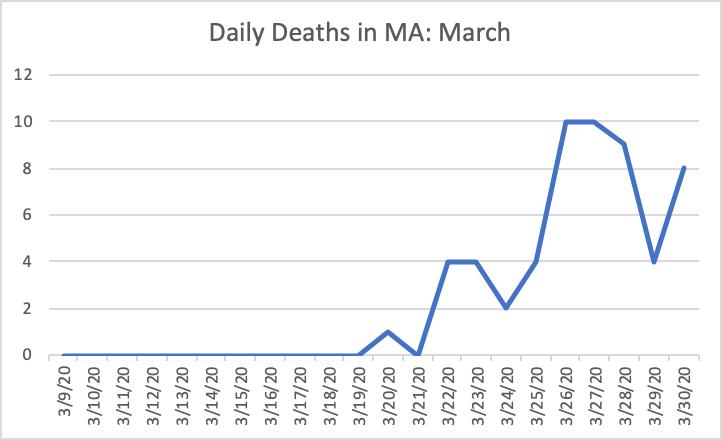

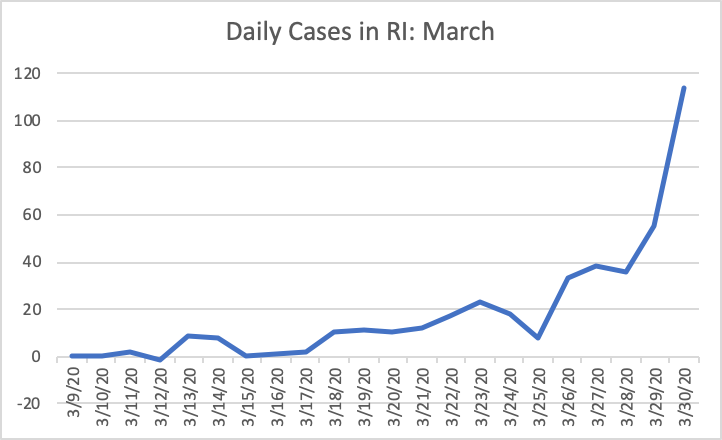

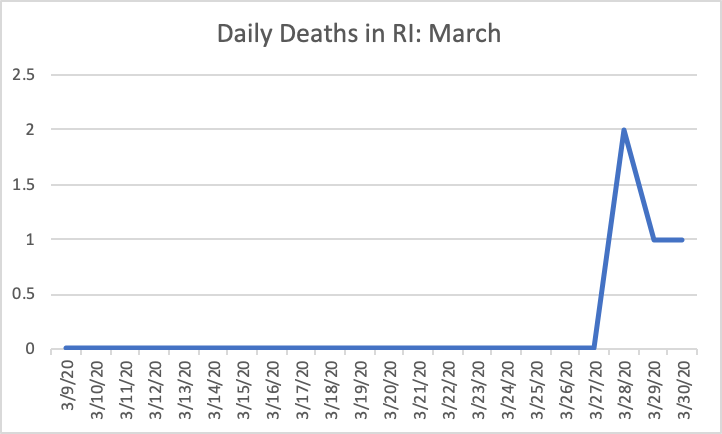

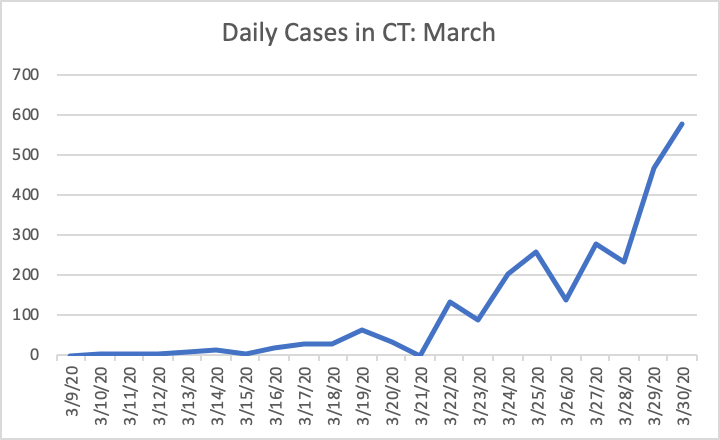

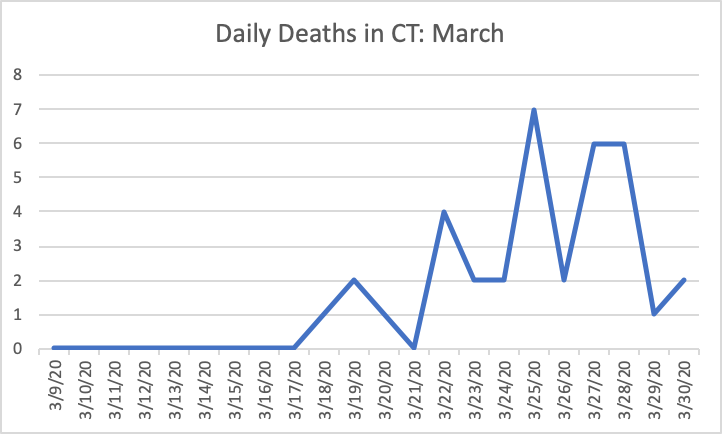

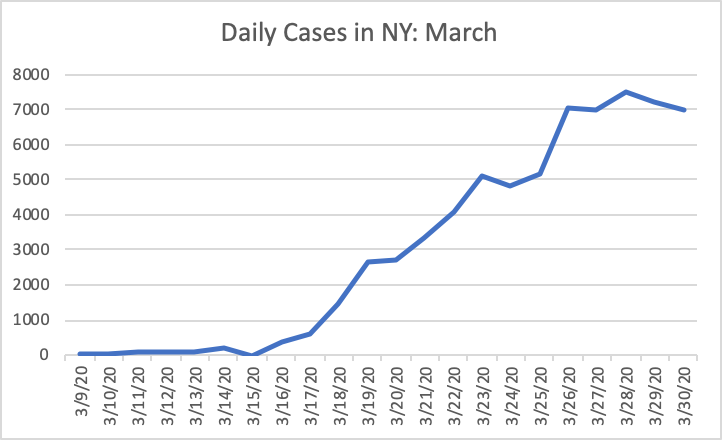

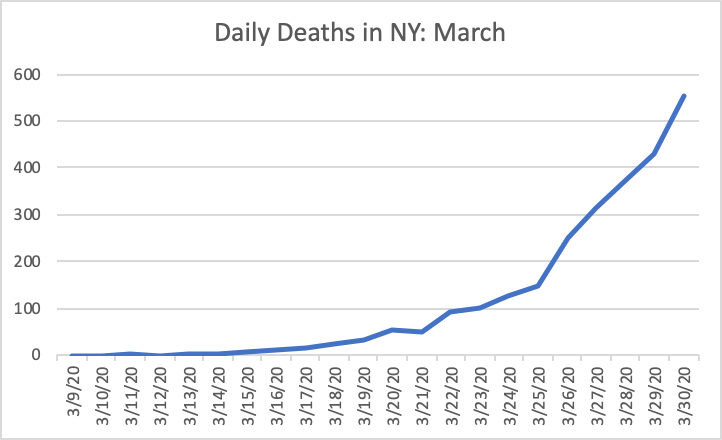

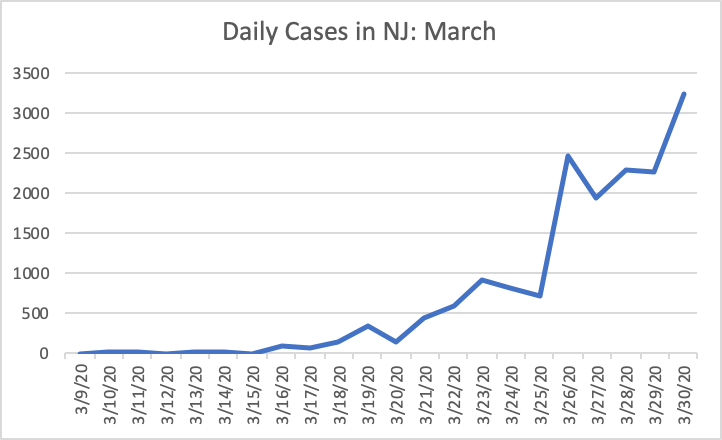

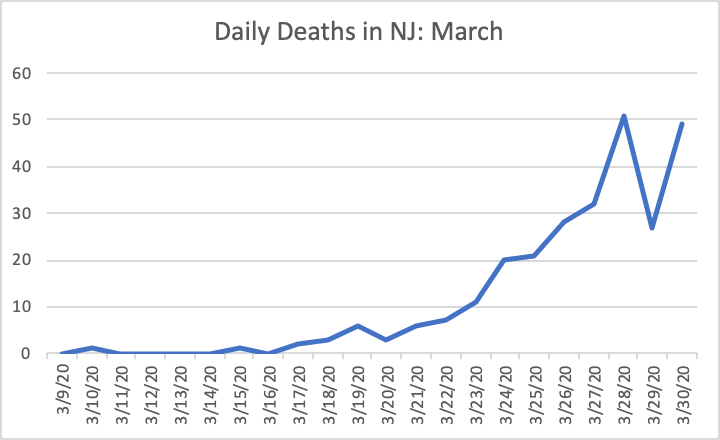

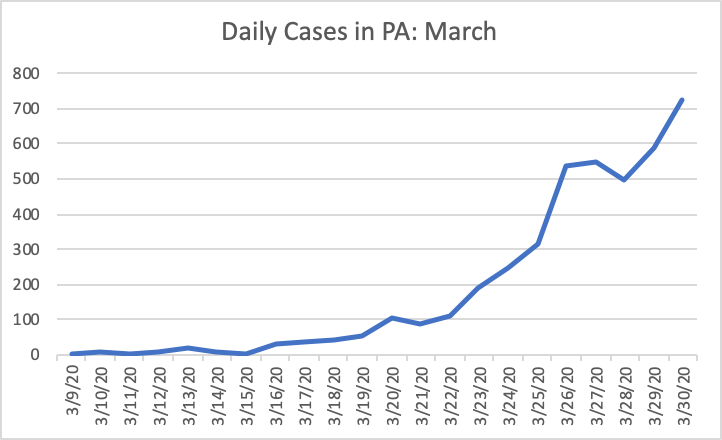

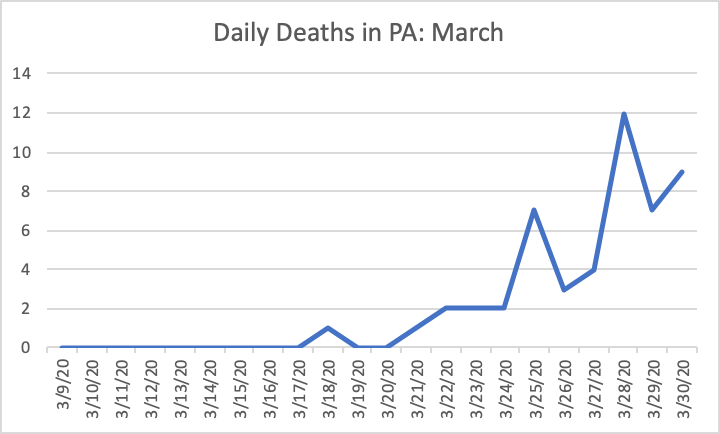

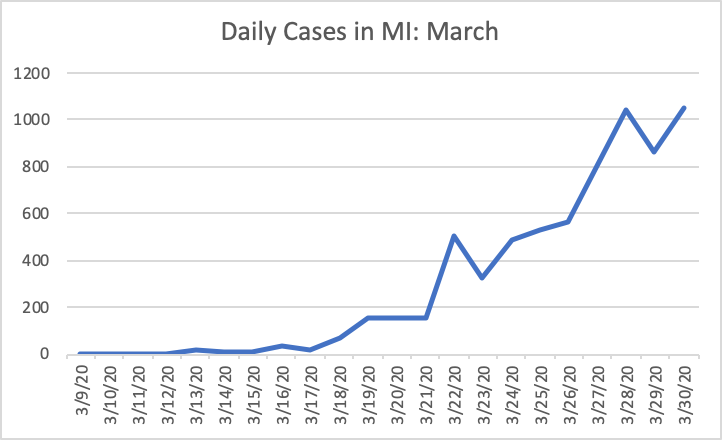

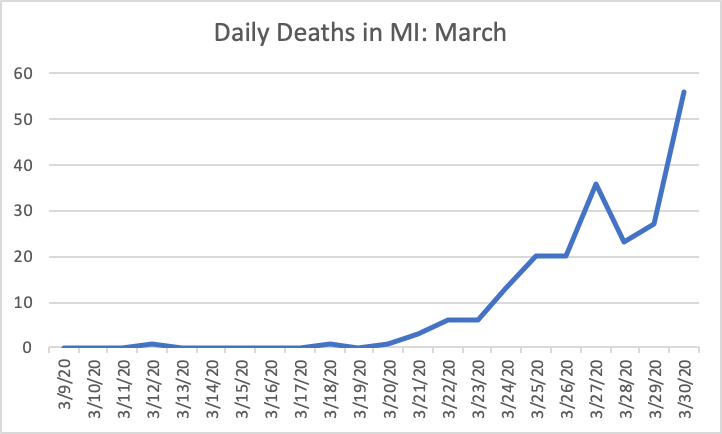

The following graphs of death rates in the Northeast in March seem to indicate that colleges and universities were most likely not only inconveniencing their students by disrupting their in-person education, but transmitting the coronavirus – which was largely concentrated in the Northeast in the first three weeks of March – all around the nation:

Despite the limited case and death data due to limited March testing, the graphs still show a clear mid-March uptick in both case and death numbers in the Northeast. These spikes coincide directly with the timeframe when Northeastern colleges and universities shut down campus and dispersed their student bodies across the country.

Case data, which at the time only reflected the small number of people being tested in hospitals and medical facilities, began spiking the same week as most of the campus closures. In Massachusetts, the daily case rate increased by 168% from between the 10th and 11th. In Rhode Island, the daily case rate increased by 350% between the 12th and 13th. In Connecticut, the daily case rate increased by 100% between the 10th and 11th. In New York, the daily case rate increased by 775% between the 10th and 11th. In New Jersey, the daily case rate increased by 233% between the 12th and 13th. In Pennsylvania, the daily case rate increased by 400% between the 9th and 10th. In Michigan, the daily case rate increased by 2,000% between the 12th and 13th.

Cases and deaths in Massachusetts from March 9 to March 30:

Cases and deaths in Rhode Island from March 9 to March 30:

Cases and deaths in Connecticut from March 9 to March 30:

Cases and deaths in New York from March 9 to March 30:

Cases and deaths in New Jersey from March 9 to March 30:

Cases and deaths in Pennsylvania from March 9 to March 30:

Cases and deaths in Michigan from March 9 to March 30:

Covid-19 deaths, which generally lag behind case spikes, followed the same pattern in late March and early April as the pandemic’s first wave peaked. Based on what we know about the virus, both statistics point to an early March community spread of the disease in these regions. By implication, the dorm closure strategy adopted by higher ed came about a month too late to achieve its intended effect of suppressing the virus in the communities where colleges and universities operate. At the same time, its unintended consequence of rapidly increasing travel from outbreak hotspots to the rest of the country is difficult, in hindsight, to deny.

Administrators Behaving Badly

Self-praise became a dominant theme of the university system’s messaging in response to the Covid-19 outbreak. University administrators credited themselves for their early decisiveness in the pandemic, and for taking responsible and swift actions to protect the public health of the communities around them. They characterized campus closures as selfless sacrifices for the general good, as well as demonstrations of higher ed’s own leadership, which other sectors of society could then emulate.

As is commonly the case in higher ed, this moralizing language rang hollow. In addition to the above-noted likely – and undetected – superspreader phenomenon arising from dismissal of students, higher ed’s response included sacrifices that were not primarily born by the people making the decisions.

While closing campuses may have been an inevitable call given the lockdown orders that followed shortly afterward, it also robbed its students of in-person classes, social interaction and extracurricular activities that they paid for. A still-unresolved ethical problem emerged with what happened next.

Focusing on the pandemic’s implications for their own finances rather than the well-being of their students, many institutions decided to continue charging full price for the privilege of diminished instructional content over Zoom. They similarly resisted refunding or prorating the many fees, housing rates, and meal plans that they collect for on-campus services, even though those services were suspended. For a typical college student living in a dormitory, these charges can quickly aggregate into the tens of thousands of dollars.

Note that we are not issuing a blanket condemnation of the decision to curtail on-campus services. When and where campuses should close or curtail activities during a pandemic are legitimate questions to investigate, with due attention given to both the efficacy of these measures and the tradeoffs they entail. When campuses close or restrict their activities, they necessarily offer a reduced level of services.

Despite this sharp decline in the quality of the typical college educational experience over the last year, American higher education has largely refused to adjust its pricing scheme to reflect the diminished services. Since higher ed’s pricing structure is already mired in a complex web of third-party payers, grant-based public subsidies, and hidden fees and charges, retaining pre-pandemic rates for dramatically diminished services quickly begins to look like a money extraction scheme.

The reasons that higher ed chose this path are many, but they usually revolve around university finances and particularly the protection of existing administrative and faculty jobs. Even before the coronavirus outbreak, American higher ed was plagued by administrative bloat – particularly among mid-level functionaries whose positions are largely peripheral to the educational core. Almost every university in America employs scores of “student services” personnel and campus activities coordinators, with entire offices devoted to campus lifestyle and branding, openly political and activist entities such as “offices of diversity” and “offices of environmental sustainability,” and untold other bureaucracies.

Indeed, in the late 2000s the total number of mid-level bureaucrats on campus actually surpassed the number of full-time instructional faculty (contrary to popular myth, full-time faculty hiring has kept pace with student enrollment over the last 50 years, although administrative growth has far exceeded both). The price tag for keeping administrators employed, in turn, falls almost entirely on tuition-paying students and subsidized by local, state, and federal level taxes.

With the onset of the pandemic, higher ed’s already-bloated state of budgetary dependency on its students and the public faces renewed turmoil. A national, lockdown-led economic downturn means a looming disaster for state and local tax revenue, and with it future public subsidies of higher ed. As with the 2008-2009 financial crisis, this decline in revenue will likely translate into reduced state and local appropriations to higher ed. After state and local revenue streams dried up during the last recession, the federal government picked up the slack for higher ed by dramatically increasing direct aid and grants to students, even surpassing the dollar amounts lost in the recession by the early 2010s. Direct federal aid money only flows, however, when campuses remain open and enrollment is increasing – neither of which apply in the Covid era.

And the other key funding source – student tuition payments – appears to be in freefall. Data released in December showed a 2.5% total undergraduate enrollment decline from 18,239,874 in 2019 to 17,778,484 for the fall 2020 semester, while community colleges took a 10.1% enrollment hit as students recognized the diminished level of services being provided by higher ed and either deferred education or sought alternative career paths.

Between looming budget cuts and dropping enrollment it is difficult to justify the bloated campus and administrative bureaucracy which is peripheral to higher ed’s educational mission. After all, it’s difficult to plan a student activities calendar, a recreational sports league, or a campus-wide carbon reduction initiative when students themselves are not permitted on campus. Despite many campuses trimming both faculty and administrative roles to meet the current financial exigencies, job protectionism will still continue to take precedence for the typical higher ed administrator – to the detriment of students’ educational needs – and an institutional aversion to reducing tuition and fees commensurate with the current diminished state of campus life.

Stunningly, some areas of campus administrative bloat have even continued to grow during the pandemic. In response to the summer 2020 protests resulting from the killing of George Floyd, many universities announced a flurry of new spending initiatives to affirm their commitments to racial diversity and inclusion. These noble-sounding initiatives appealed to widespread public outrage over the killing of Floyd and the larger problem of police brutality in our society. In practice however, they offer little in the way of improving student well-being on campus. Instead they create scores of new highly-paid jobs for university administrators, as well as dedicated funding for these new hires to spend on themselves and on securing their own permanence within the university bureaucracy.

Examples abound, and usually involve some combination of (1) creating new “diversity” administrative positions and (2) dedicating new funding and mandates for curricular content. David Leebron, President of Rice University, announced on June 16th that the school would create “new management positions geared towards race, diversity, and inclusion. Leebron added that there will be a diversity and cultural understanding class included in the required orientation coursework.”

Brown University released a letter on June 1st, signed by 21 senior faculty members, pledging to “implement coursework designed to promote equality and justice.” CalTech, on June 4th, announced that it would be introducing a mandatory unconscious bias training initiative. Christopher Eisgruber, President of Princeton, issued a statement on June 22nd that “there will be a new summer grant program for serving racial inequalities and injustices and new classes related to anti-racism.” Larry Bacow, President of Harvard, released a statement on June 22nd announcing the hiring of a new chief diversity and inclusion officer.

While campus diversity programming of this type is often presented in ethical terms, this moralizing language often obscures less-noble financial motives as well as the general ineffectiveness of these initiatives at achieving their stated goals. A 2018 empirical analysis found no statistical evidence that hiring a campus diversity officer “alters preexisting trends of increasing faculty and administrator diversity” from historically underrepresented racial and ethnic minority groups. They do, however, provide high-paying jobs for administrators, drawn almost entirely out of student tuition payments.

Administrative bloat is not cheap, and the drive to expand the campus diversity bureaucracy is no exception. In one widely-cited example, the University of Michigan employs almost 100 administrators for diversity programming. A quarter of these employees make six-figure salaries, and their pay and benefits collectively cost about $14 million per year to maintain. This translates into about $300 from every student enrolled in the university.

Even during normal times, we should question the justice of a program that transfers vast amounts of money from students – a large percentage of them facing economic precarity, and many of whom come from underrepresented minority groups – to what is essentially a jobs program for upper middle class administrators. Why not rebate tuition instead? Or if increasing underrepresented minority access to campus is really the goal, why not spend this money directly on scholarships?

During Covid, one legitimately wonders whether these resources would have been better mobilized for socioeconomically disadvantaged students struggling to transport, house, feed, and support themselves following the universities’ hasty expulsion of their students from campus, and subsequent reduction in services.

From the student’s perspective, charging full rates to keep administrative functionaries employed even as they offer few or no services smacks of a bait and switch and institutions are starting to face litigation from students who feel cheated out of the in-person services they paid for. For example, Brown University was issued a class action lawsuit in May of 2020 by students seeking reimbursement of tuition, room, and board following the school’s March 22nd closure of accomodation and March 30th shutdown of in-person schooling and extracurricular activities. According to Providence Journal,

‘[t]he complaint says Brown ‘continues to charge for tuition, fees, and room and board as if nothing has changed, continuing to reap the financial benefit of millions of dollars from students. Defendant does so despite students’ complete inability to continue school as normal, occupy campus buildings and dormitories, or avail themselves of school programs and events.’

Moreover, the legal team that represented the Brown students filed similar suits on behalf of students at Boston University and Vanderbilt University. The trend of disgruntled college students can be found at New York University, where “many students are asking for their money back.” CNBC reports that, “close to 10,000 students at NYU […] signed a petition calling for partial tuition refunds.” NBC put the situation bluntly in their accurately and depressingly titled article, “‘Everyone’s losing’: College campus closures a stark reality for students.”

Despite the omnipresent rhetoric on college campuses of equity, inclusion and consideration, their eviction policies, diminished services, and habit of continuing to charge full-rate tuition and fees fly in the face of their oft-touted commitments to social justice. This was aptly captured by NPR on March 17, 2020, in a report on the displacement of disadvantaged students, “When Colleges Shut Down, Some Students Have Nowhere To Go.”

How Higher Ed Failed its Students during Covid

NPR reported in early March (2020) that the CDC advised school administrators to “help counter stigma and promote resilience on campus… [to] counter the spread of misinformation and mitigate fear… [to] speak out against negative behaviors, including negative statements on social media about groups of people.” Despite this early warning from the CDC, school administrators have implemented draconian policies that harshly punish those students who even slightly deviate from the college’s Covid guidelines and promote an environment of distrust and judgmentalism.

The new norm on many campuses focuses on punitive enforcement – on suspensions and expulsions – for students caught in unapproved social interactions, which may even entail something as simple as gathering with too many of their peers in a single space or venturing off campus without approval.

While the “appropriate” level of social distancing measures on campus remains open to debate and deliberation, many policies adopted thus far display an overarching paternalism resulting in a campus culture that reduces paying students from working-age adults to closely-supervised residents of a post-secondary boarding school. Summarizing the thrust of these policies, Will Creeley of the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education noted many “schools are taking a suspend first, expel first, and ask questions later stance.”

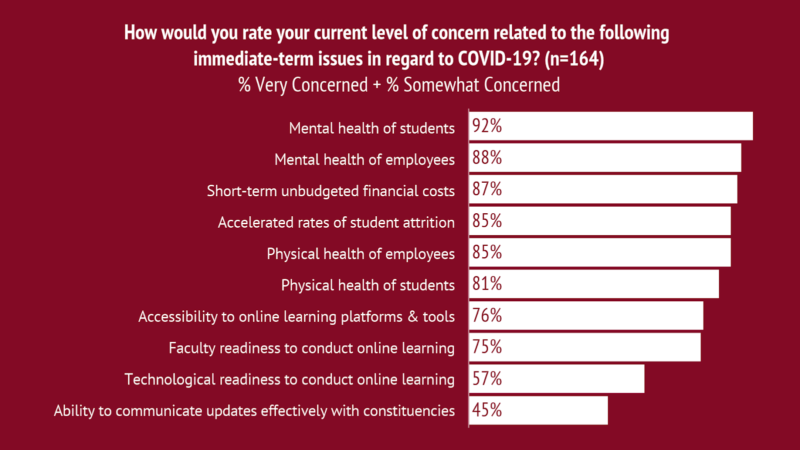

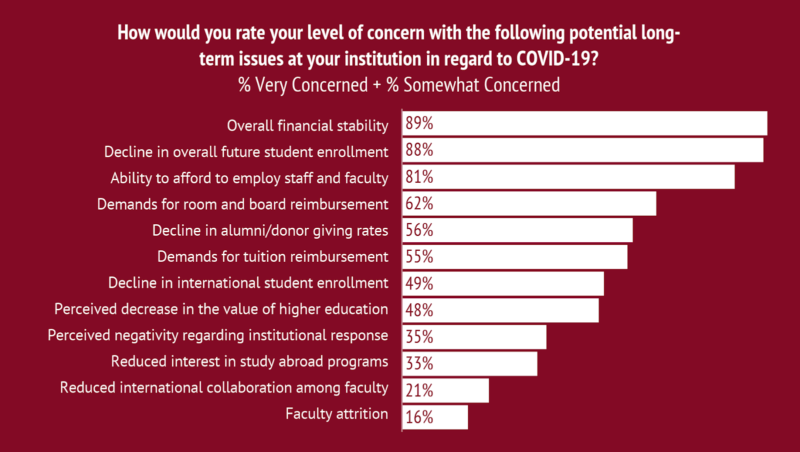

Higher ed’s lack of concern for student well-being and agency in their own education has manifested in other ways. On March 27th, shortly after the nationwide school closures, Inside Higher Ed reported data from a survey of 172 presidents of colleges and universities.

The survey found that college presidents’ highest stated concern was for the mental health of their students and faculty, yet “only 18 percent said they had invested in additional mental or physical health resources… Of the large majority of presidents who said they had not yet invested in additional physical or mental health resources, fewer than half, 44 percent, said they expected to do so down the road.” The revealed preferences of college administrators often diverge from their moralistic language of concern for their students, and nowhere is this more apparent than the way they have approached Covid-19.

Despite anticipating the grave toll that strict lockdown policies would wreak on the mental health of their students – as well as 89% being either somewhat or very concerned about the overall financial stability of their institution – school leaders embraced “a very strong herd mentality” and followed the lead of MIT, Stanford, and Harvard. The presidents of these highly reputable institutions issued a moral injunction in the New York Times: “We Lead Three Universities. It’s Time for Drastic Action.” In seeking to reduce population density and slow the spread of the virus, the three presidents implore other universities to follow their lead by:

sending virtually all of our undergraduates home; asking faculty to swiftly bring all instruction online; canceling academic, athletic, artistic and cultural events, and nearly all in-person meetings; shutting our libraries; and asking everyone who could work remotely to do so right away.

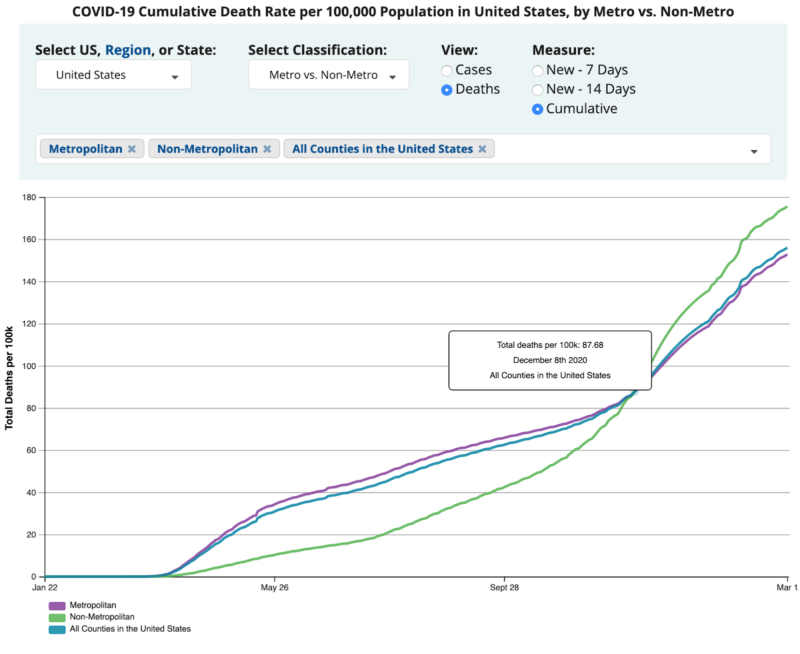

The presidents’ hopes that reducing population density would be directly correlated with mitigating the deleterious impact of the highly virulent pathogen turned out to be false. Data from the CDC show that, while metropolitan regions were impacted earlier on than non-metropolitan areas, the cumulative deaths per capita in non-metropolitan areas equaled that of metropolitan areas around December 8, 2020 and significantly surpassed the metropolitan death rate by March 1, 2021.

Ironically, despite their policies potentially contributing to the spread of the virus to areas in which the virus had not yet reached, the subtitle of the presidents’ piece in the Times was, “[o]rganizations nationwide need to get ahead of the coronavirus, even if it’s not in their community yet.”

In the aforementioned piece by NBC, “‘Everyone’s losing:’ College campus closures a stark reality for students,” the author remarks on just how stark a reality that can be: “Not everyone on a college campus, no matter how elite, has a safe home to return to, and some can’t afford the trip back home.”

Students at Harvard, arguably the most elite institution of higher learning in the U.S. (if not the world), were faced with such a daunting reality. At the outset of the campus closures The New York Times interviewed Abigail Lockhart-Calpito, a freshman, who poignantly explained how “home for a lot of [students] is campus,” especially for those who, like herself, are on full financial aid. The student goes on to explain how capriciously getting kicked off of campus – and losing the room and board provided – felt “like an eviction notice.”

Tabitha Escalante, another Harvard undergrad, was forced to cancel her flight – forfeiting $250 – as she scrambled to figure out how to store her belongings following the University’s last-minute ruling to not invite students back following spring break. Adding insult to injury, her waitress mother was forced to drive 11 hours from Ohio to retrieve Tabitha and her items, foregoing the wages and tips that sustain her and her family.

Aaron Vanek, a junior at NYU’s Tisch School of Arts, had no way of getting home to Minnesota for spring break as a family member had already tested positive. Staying at a generous friend’s home in Maryland, Vanek was then compelled to travel back to New York, store his belongings, and figure out how to get home from NYC after NYU reneged on resuming in-person classes on April 19.

Our own experiences attest to similar situations. Jack Nicastro was personally paid by a Californian student of Columbia University to package and ship her clothes, furniture, and other belongings home to the West Coast after she faced a hasty eviction with no other means to retrieve her possessions. While such an option may be viable for those who, like this student and her family, could afford to pay several hundred dollars for UPS ground shipping, handling, and Jack’s amateur packaging services, such an expensive solution is financially impossible for many low-income students.

The situation was even worse for some of the most vulnerable campus members: international students. The Times explains how undergraduate students, typically on F visas, are permitted only one online course per term or else forfeit their right to remain within the U.S. The circumstances worsen for those students in the U.S. for vocational training – typically from worse socioeconomic backgrounds than college students – who are permitted precisely zero online terms, i.e. being forced into a remote education means they must leave the U.S.

That said, Smith, Amherst, and Harvard issued prorated refunds of room and board for their students. Moreover, Harvard assembled staff and resources midday Wednesday, March 11, to provide guidance and financial aid predicated on their students’ financial aid status in assisting them to return home; not great news for those students with no home to return to, homes at which abusive family members reside, or those forced to travel abroad to countries even worse off with Covid-19 and with even harsher lockdown policies.

The Moral Mess of Higher Ed During Covid

The lessons for higher ed from Covid-19 will continue to be studied for decades to come. Counterfactuals are hard to come by, as almost all colleges and universities experienced some form of on-campus closure. Even a year later, most colleges remain under severely restricted operations and will continue to offer diminished services for the foreseeable future.

Weighing the merits of these decisions requires deliberation and consideration, as do questions of higher ed’s priorities in the coming months and years. Despite a flurry of high-minded statements from college administrators committing themselves to public health and responsibility over the last year, their own actions have paid little concern to the primary constituency on which investments in higher education are sold to the public: the students these institutions serve.

Setting aside the rhetoric of self-praise, we find a record of hasty and self-serving decisions that not only failed to deliver on their educational mission to their student constituencies but may have even worsened the pandemic’s nationwide spread in the crucial early months of the outbreak.

Long before Covid-19, many of higher ed’s business operations could be characterized as a self-serving job security program for administrators and faculty, fueled by the tuition payments of students who had little say in the product they received and, more broadly, the taxpayers who sustain their operations. With little surprise, the pandemic has exposed and intensified these faults.