Rising Interest Rates and Inflation

Low interest rates are a sign of easy money. At least, this is what I was led to believe before I studied monetary policy. It is easy to be led toward this sort of thinking. The central bank, seeking to boost spending, lowers interest rates. In doing so, it makes borrowing relatively cheap and encourages higher levels of consumption and investment.

The problem with this view is that it holds the interest rate as a policy tool rather than a reflection of economic conditions. Another way of viewing the interest rate is that it reflects the expected return on investment. The interest rate is the rental price of money. The greater the level of profit opportunities in the marketplace, the higher the rate borrowers will be willing to pay in order to invest the borrowed funds in these profitable activities. Without intervention from the central bank, changes in interest rates tend to reflect changes in the level of productivity.

The confusion arises due to short-run fluctuations that are inherent in financial markets. During an economic boom, banks tend to lower the level of reserves and suppress the rate of interest. Over the course of the boom, however, rates tend to rise. They just rise at rates slower than they would without the lowering of reserve levels. Toward the end of the boom, interest rates may spike as a means of restricting credit in an increasingly speculative market. This spike is only temporary. As the downturn displaces an economic boom, interest rates tend to fall.

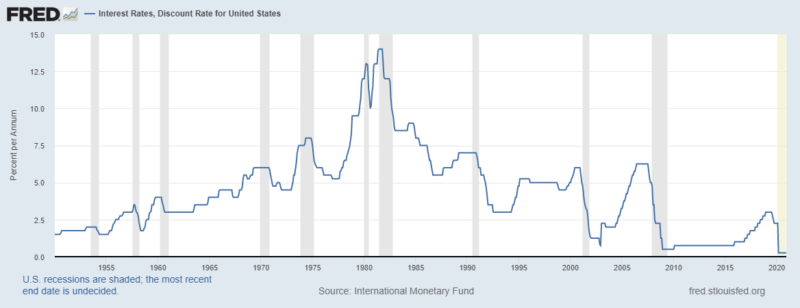

If we consider actual interest rate data, you will notice that interest rates tend to rise before the onset of recession (marked in grey) and tend to fall during or shortly after a recession. This pattern isn’t because the central bank decides to raise rates during a boom and allow rates to fall during a recession. Central banks tend to follow movements in interest rates generated by the market. The central bank might attempt to alter these rates and can succeed to a limited extent. If the central bank does not want to foment difficulties from inflation, as occurred during the 1970s and early 1980s, it will respond to pressures generated by financial markets sooner rather than later.

Inflation, Interest Rates, and the Asset Valuation

There is a lot of talk in the market about a fear of rising rates. If you consider a naïve interpretation of the present value equation, this makes sense. The present value of an asset is equal to its expected future value controlling for the interest rate compounded over the time period in question. Assuming that interest is only compounded at the end of each period, this is described by the equation: PV = FV/(1+r)^t. So if the interest rate rises in this equation, the present value would fall. But the interest rate forms in light of investor expectations about changes in the future value of assets relative to the present value. Or in other words, the interest rate will increase in response to expected increases in productivity that also positively increase the expected future value of productive assets.

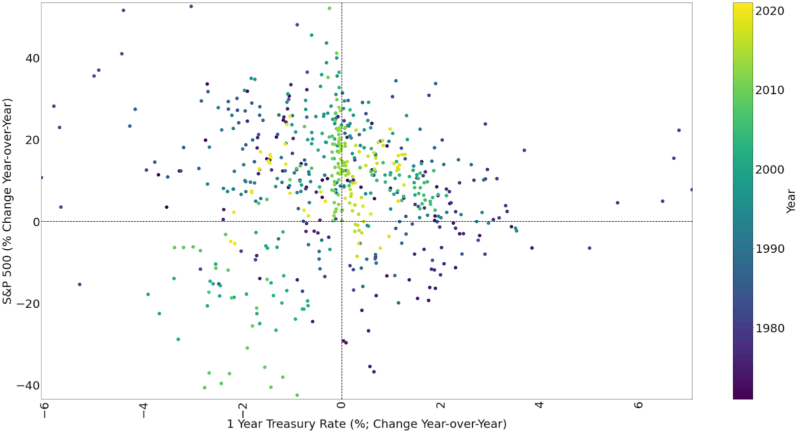

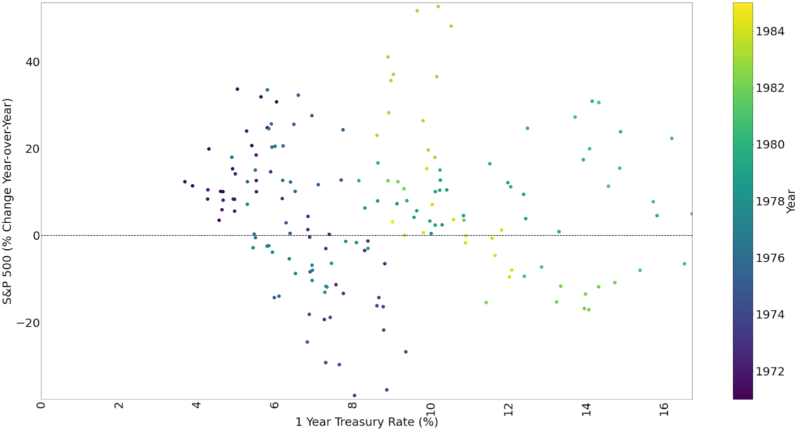

If we compare changes in nominal interest rates with changes in the value of the S&P 500, we observe no obvious, systematic correlation. Sometimes a sharp fall in rates is associated with a rise in the value of equities. Sometimes a fall in rates owes to a recession and is associated with a fall in the value of equities. During the late 1970s and early 1980s, a period with relatively high inflation – sometimes in double digits – the data shift outward, away from the origin so that a given level of S&P growth is associated with a higher nominal interest rate.

Of the 96 monthly observations available between January 1978 and December 1985, the average monthly value of the S&P 500 increased in 71 of these months. During this same time, the median percent change in the S&P 500 was 8.72%. The median rate for a 1-Year Treasury was 10.18%.

Compare this to the period between January 1970 and December 1977. Of the 84 monthly observations, only 51 are positive. For this range, the median year-over-year change of the S&P 500 was 6.54% and the median rate for a 1-Year U.S. Treasury was 6.15%.

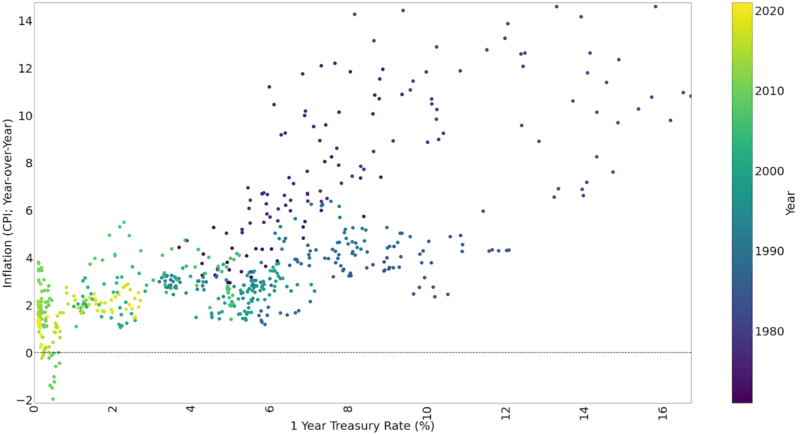

We do observe a strong, positive correlation between observed inflation over the previous year and the rate of interest paid on U.S. Treasuries. This should be no surprise. In his study of interest rates, Irving Fisher identified that observed rates reflect expected inflation. Investors integrate inflation expectations and adjust their demand for bonds in response.

Whatever trade-off there might be between the value of equities and interest rates, this relationship can shift during periods of significant change in expectations. Further, these values tend to be positively correlated across the business cycle, with interest rates and equity values increasing during a boom and falling during a recession.

Interest Rates and Equities Today

Recently, interest rates on long-term U.S. Treasuries have been rising. The rate on 10- and 30-Year Treasuries has moved above pre-Covid-19 levels while the lower part of the yield curve remains near zero. Many are concerned that rising interest rates could put the brakes on recovery. This sort of thinking is just plain wrong.

James Gwartney recently explained that rising interest rates could be associated with increasing velocity of money. Rising inflation expectations can support a rise in interest rates that increase the average rate of circulation, making expectations of higher inflation a reality. As occurred in the late 1970s, this would likely shift and dampen the trade-off between interest rates and equity prices. If this is the case, inflation and interest rates will tend to move in the same direction at the same time.

Despite rising interest rates over the last month, Jerome Powell has reassured investors that he will not move to increase rates any time soon since “[t]he economy is a long way from our employment and inflation goals, and it is likely to take some time for substantial further progress to be achieved.” The underlying assumption seems to be that inflation will not take off until unemployment falls. It appears that the experience of stagflation during the late 1970s and early 1980s is absent from the memory of policy makers. Or they think the experience is irrelevant to present circumstances. In his favor, Powell is likely considering the expected rate of inflation implied by the 10-Year TIPS spread, currently at 2.36%. It is unclear, though, if Powell would be willing to raise the federal funds rate target in the event that inflation takes off in a manner envisioned by Gwartney. Will he revise his views if he finds that inflation can, in fact, “change on a dime?”

As I have explained recently, a 5 to 10 percent jump in inflation expectations could be enough to set off a fiscal crisis for the federal government. And a fiscal crisis could be enough to generate a crisis of confidence in the dollar. There are numerous traps to avoid on the road ahead. Yet, monetary and fiscal policy both continue on expansionary paths with the greatest boldness that we have seen since the chairmanship of Arthur Burns.