Quartering and its Importance to the American Revolution

When people discuss the factors that ignited the American Revolution, the role of taxes such as those on stamps and luxury items tends to be emphasized. The role that the quartering of troops played in fueling the conflict tends to be minimized.

After the French and Indian War had been concluded, British military commanders decided that some British troops ought to remain in North America. It was also decided that the colonists should pay for a larger share of the costs of those troops. One of the mechanisms by which this financing was to be done was through the quartering of troops in local buildings if military barracks were insufficient. Economic theory suggests that forcing the provision of a service or good for a particular individual is the same as a tax.

Thus, quartering is a tax in kind. However, it was impossible under law to force an innkeeper or a landlord to provide shelter at no cost to soldiers – compensation had to be offered. Thus, the tax that quartering imposed had to be financed via the proceeds of other taxes. The British expected, as is made clear by the Quartering Act of 1765, that the colonial legislatures would raise taxes to finance those compensatory payments. The colonial legislators, especially those in Massachusetts, stubbornly refused to increase their own taxes. They argued that Britain had to compensate (i.e. taxpayers in Britain rather than in America).

Normally, the story ends there. The taxes were not raised. The troops being quartered were an irritant but it paled in comparison to irritants like the Stamp Act. In a recent article in Social Science Quarterly, Jeremy Land and I argue that quartering was a much larger irritant than commonly believed. We argue that this is because the literature has ignored important insights from the field of labor economics.

When British soldiers arrived in the American colonies, they were expected to complement their pay by working for civilian employers in their off-time. This meant that there was an increase in the supply of labor in the areas where they were garrisoned. This depressed wages. However, when they arrived in these areas, they also increased the demand for goods and services. In turn, that meant increased demand for labor in order to produce such goods and services.

Normally, that shift in demand would have pushed up wages. We say “normally” because the mechanism we just described is the one that economists who study immigration frequently observe: immigrants increase both demand and supply for labor which yields negligible effects on wages. However, the quartering of troops stifled the demand-side effect while the supply-side effect operated in full.

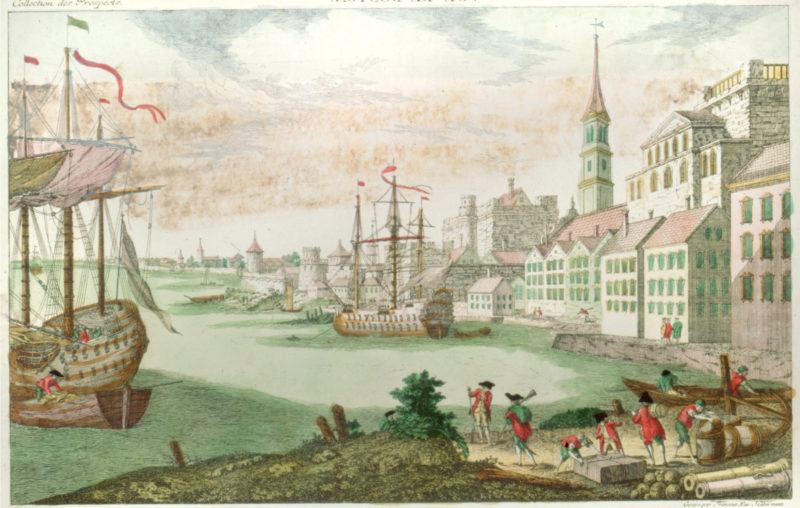

To measure the importance of that mechanism, Land and I compared Boston with Quebec City. Both cities were selected because they had large garrisons. However, the size of those garrisons moved in opposite directions in both cities. In Quebec City, which had been seized by the British in 1759 and formally ceded to Britain by France in 1763, the garrison was gradually reduced between 1763 and 1775. Whereas it represented more than 20% of the local population in the early 1760s, the garrison’s size was reduced gradually to the point that it represented only 1% of the local population. The garrison was also smaller than that which the French had placed when they were in possession of the city. In Boston, the garrison was gradually increased to 12.5% of the local population. Thus, we compare two cities that experienced different changes in troop quartering. More importantly, Boston was the city that revolted while Quebec City’s inhabitants (despite being French and Catholic which would have made them ill-disposed towards Britain) stubbornly remained loyal to the crown.

In Quebec City, we find that as the garrison was reduced in size, nominal wages went up. Moreover, we also know that the prices of certain goods and services such as firewood and housing fell rapidly. The goods and services whose prices declined were locally produced and were not typically traded over long distances (either because they were services or because they were too costly to transport). Because their prices were essentially determined by local factors, the shrinking of the local garrison reduced the demand which meant that prices went down. This meant that there was a marked increase in real wages.

By 1775, wages in Quebec City were at a historical high. Moreover, the British refused to impose local taxes on their new colonists. Compensation for quartering was financed through the appropriations that the House of Commons in London had voted for and that British taxpayers had paid for. In contrast, Boston experienced a fall in nominal wages and an increase in the cost of locally-traded goods and services as the garrison was increased. The result is that tensions in Boston between soldiers and locals gradually translated themselves into violent events between the two. It is thus unsurprising that Boston was a hotbed of revolutionary activity while Quebec City felt no need to join the Revolution.

Quartering imposed a serious burden on local populations, especially laborers and poorer households. Its incidence is harder to measure than that of stamp, sugar and tea taxes. However, it is probably one of the most underappreciated major causal factors of the American Revolution.