Legal Moonshine At Last

Years ago, I was working in Alabama and a maintenance man very sweetly gave me a jar of white liquor as a gift. He explained that it was made by a family friend, and far better and healthier than “government liquor.”

Initially confused, I figured out what he meant by that phrase: anything sold in a package store. Stay away from that stuff, he said. So, breaking bad, I tried a spoonful of the moonshine.

That was more than enough. My lips burned after for an hour.

I didn’t know it at the time but this moonshine was just the beginning of one of America’s booming industry: artisanal beverages, they are called. This covers breweries, distilleries, wineries, and cideries. The growth has been phenomenal over the last ten years.

It all began with Jimmy Carter’s great act of deregulating the breweries. Since then the industry has boomed, especially recently. Double-digit growth in the number of distillers is now normal. Wine is the same. There are 8,000 breweries in the US today, compared with one-tenth of that 25 years ago. Cideries seem poised for a big expansion.

It’s fair to say: this is a craze. And a wonderful one.

I set out with friends on Sunday to visit as many as possible in the Hudson Valley of New York. We made it to 7, which I think might be about 3% of them in some 20 square miles. My friend joked that “basically if you knock on any door in the Hudson Valley, they will try to sell you their artisanal beverage.” That’s only slightly exaggerated.

Many of them are just mind blowing. I was sitting at the Olde York Farm Distillery and Cooperage, sipping on a concoction made of a rhubarb-based vodka. I asked the owner/server/distiller what is the difference between what he does and what moonshiners in the South do. His answer came quick:

“I have a license.”

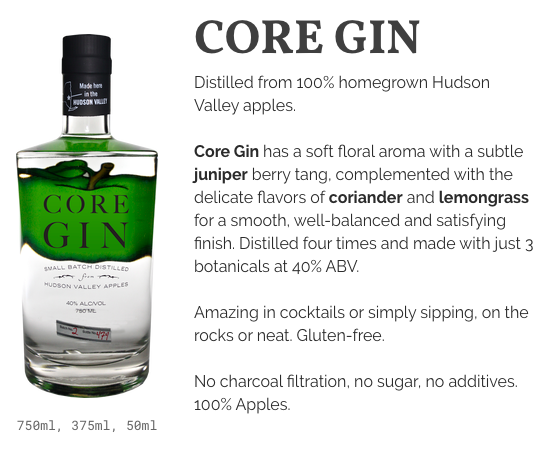

For example, I tried an amazing gin at Harvest Spirits in the Hudson Valley. It’s the most interesting drink, a front of juniper just as gin should have but you can detect a deeper foundation of…apples. I can completely imagine that this would be a huge hit with customers around the country at liquor stores and gin bars. No such luck! The company can’t even let this stuff cross the state line into Massachusetts. The regulations prevent that.

Why is this? This country has a long and strange relationship with the private production of alcoholic beverages. If you ever think that this land of the free is a perfectly normal country, never forget that the production and consumption of alcohol was banned by constitutional amendment between 1919 and 1933.

Prohibition was based on the finest settled science of its day. It went like this. There are lots of social problems out there, such as absentee fathers, pauperism, early death, lazy workers, broken families, and derelicts strewn all over the big cities. The social scientists examined each of these problems and found a common denominator: liquor. So, the thinking went, the answer is rather obvious. Ban the stuff and you get rid of the problem!

So pervasive was this theory in the late Progressive Era that you dared not contradict the claims, lest you be accused of defending the evil liquor industry or being a drunkard yourself. The handful of people who spoke out against the zany push had to clarify that they themselves do not indulge, lest they instantly be discredited.

And so it happened. We were suddenly Saudi Arabia. Then the disaster unfolded over the course of 10 years (violence, political corruption, health risks of bathtub gin, the wild fashions for underground cocktails) until exhaustion set in, FDR was elected president, and the new administration re-legalized it, to the cheers of Main Street.

Still, the remnants of Prohibition exist. There are still blue laws. Some counties don’t allow private liquor sales. We have absurd age restrictions on drinking, which have driven college kid

s to turn their campus experience into one big speakeasy, with kids unsafely hiding and binging in dorm rooms, frat houses, and private homes, endangering everyone. This is how they learn to drink – and it is not at all civilized.

It’s generally true now that American culture has a pathological relationship with its drinking issues. A culture of getting away with it is still with us, and it is sustained by the endless regulations that govern the stuff. Every state, every county, every town and city, plus the federal government itself, pushes laws, and they are contradictory, onerous, benefitting of large producers and distributors, and extremely unfriendly to the customer.

The laws are so complicated that experts can barely understand them, and never mind the people who work at these artisanal beverage companies. On my tour of producers, I would often ask the server why I can’t buy this wine at my local store. They always demurred: ask the owner because understanding the law is too rich for my blood.

I went on my tour with economist Max Gulker, who started gaining the impression that this whole industry is in an unsustainable boom, with everyone opening a beverage company just because they can. He speculated that in a truly free market, many of these places would be acquired by larger companies, just as we’ve seen in the non-alcoholic beverage industry.

That could be but I must admit that there is a certain charm to the localization of all of this. Most customers want to know: are the grapes grown here, are your distilleries on the property, are these your own apples, and where do you get your hops. What this tells me is that this industry is about more than just the stuff you drink; it is about the ethos of localization and personalization. There is a charm here.

All hail local! But there’s a catch. Global capitalism has made it possible. From the casks and stills to the marketing and information sharing, every one of these local places depends on and benefits from a globally cooperative infrastructure that has driven down entry costs and made the equipment affordable. It was once the case that owning a winery was only the dream of the richest families. Now it seems everyone is involved.

Under consolidation, would some of this charm go away? Maybe. Unless the new owners see the point of retaining the look and feel of local.

The producers are growing in number. The customer base is expanding. Everyone is winning. At some point, the regulations have to give way.