Inflation On Target in December

New data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis shows that inflation has slowed significantly over the last year. Prices are now growing at a rate consistent with the Federal Reserve’s inflation target.

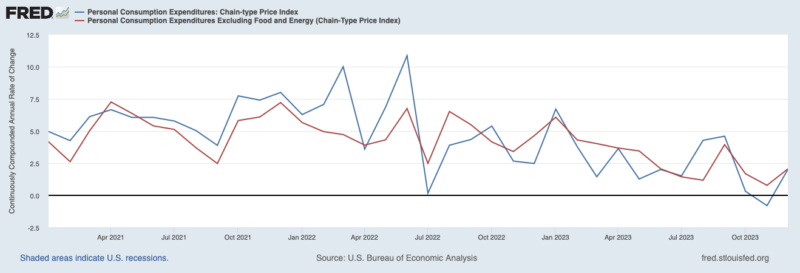

The Personal Consumption Expenditures Price Index, which is the Fed’s preferred measure of inflation, grew at an annualized rate of 4.2 percent in Q1-2023. PCEPI inflation averaged 2.5 percent over Q2 and Q3. In Q4, it was just 1.7 percent.

Core inflation, which excludes volatile food and energy prices and is thought to be a better predictor of future inflation, has also declined. Core PCEPI grew at an annualized rate of 5.0 percent in Q1-2023 and 3.7 percent in Q2. It has grown 2.0 percent over the last two quarters.

The Fed was late to recognize rising inflation in 2021 and slow to begin tightening 2022. But it eventually tightened monetary policy—and tight monetary policy has helped bring inflation back down to the Fed’s 2-percent target. If anything, the Fed is now ahead of schedule. In December, the median FOMC member projected PCEPI inflation would be 2.4 percent in 2024 and 2.1 percent in 2025. Given the most recent data, I expect inflation will be around 2 percent over the next year.

Has the Fed Really Done Enough?

I expect some will remain concerned about inflation and call for the Fed to do more to bring inflation down. They might point to annual rates, which still look high. The PCEPI grew 2.6 percent over the last twelve months. Core PCEPI grew 2.9 percent. Both are clearly above the Fed’s 2-percent target. There’s no denying that! But one must remember that these rates are annual rates. They show us how much prices have risen over the last 12 months. And much of the increase in prices observed over the last 12 months occurred more than nine months ago. Inflation has been much lower, on average, over the last nine months. Indeed, inflation is now in line with the Fed’s 2-percent target.

Of course, one might accept that inflation is back down to 2-percent and nonetheless worry that it will resurge in 2024. That is, after all, what the median FOMC member has projected. But I think such concerns are unfounded. At present, there’s no good reason to worry that inflation will pick back up.

What Caused the High Inflation?

To see why I am not worried that inflation will pick back up, consider the major sources of inflation since January 2020:

- Pandemic-related supply disturbances

- Russia’s invasion of Ukraine

- Loose monetary policy

The first two sources of inflation are what economists refer to as real shocks. They reduce our ability to produce goods and services, pushing prices up. However, they are also both temporary shocks. As supply constraints associated with the pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine ease, our ability to produce goods and services recover. That puts downward pressure on prices. In the absence of another disruptive wave of COVID responses or a ratcheting up of military activity in Eastern Europe, we should not expect these sources to result in future high inflation.

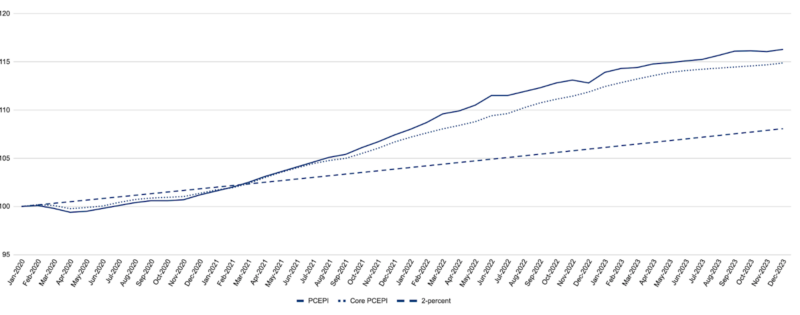

Of course, most of the inflation observed since January 2020 cannot be attributed to real shocks. This should be obvious to anyone who recognizes that supply constraints have eased and yet prices remain well above their pre-pandemic trend. As shown in Figure 1, prices were 8.2 percentage points higher in December 2023 than they would have been had inflation averaged 2 percent since January 2020.

Most of the inflation observed since January 2020 was due to loose monetary policy. The Fed accommodated large fiscal expenditures associated with the pandemic. Then, when nominal spending growth surged in the back half of 2021, it failed to tighten monetary policy promptly.

If monetary policy were loose today, one might reasonably worry that inflation will resurge in 2024. But it isn’t. Monetary policy remains very tight. Interest rates are much higher than they were just prior to the pandemic. And the Fed is no longer accommodating expansionary fiscal policy. Indeed, its balance sheet has declined from $8.97 trillion in April 2022 to $7.67 trillion in January 2024.(That’s still much bigger than it should be. But at least it is heading in the right direction.) So long as the Fed holds interest rates high and continues to shrink its balance sheet, inflation will fall.

Conclusion

There is a lot to lament about monetary policy over the last three years. The Fed should have recognized the surge in nominal spending growth in the Fall of 2021 and taken steps to offset it. Instead, it allowed prices to rise rapidly. More recently, however, it has kept monetary policy sufficiently restrictive to slow nominal spending growth, and bring inflation back down.

Is it possible that unforeseen shocks will push inflation back up? Sure. That’s always a possibility. But the disinflationary trend is clear. And the forces that pushed inflation higher in 2021 and 2022 have since dissipated or reversed. Consequently, inflation is back on target.