Eating The Rich Won’t Feed the Beast

Wealth in a free society is a rough tallying score of how much economic value someone has provided to the rest of us. A rich person’s wealth — bar inheritance and cronyism — is a testament to how much they enriched us.

As Johan Norberg writes in The Capitalist Manifesto

If anything remains of the revenue when employees, suppliers and lenders have been paid for their efforts, it is called ‘profit’ and we are very angry when it’s a large sum. In fact, we should be happier the bigger it is, because it shows that everyone else in the chain has been paid first and that the company has still succeeded in its ambition to transform time and resources into something we value.

Billionaires aren’t policy failures, but clear indications of (distributed) value created: jobs and incomes, improved goods and services, and a better standard of living. “Capitalism,” said the Austrian economist Ludwig von Mises in a Mont Pelerin lecture in 1958, “is not simply mass production, but mass production to satisfy the needs of the masses.”

But the rich don’t pay their fair share, you might say. On the contrary, any serious investigation reveals that they pay everyone’s share. Some one-fifth of federal tax revenue already comes directly from the incomes of the richest one million American households. The incomes of the highest-earning 20 percent of households more or less bankroll the federal government. he Congressional Budget Office in its “The Distribution of Household Income” report notes:

High-income households generally pay a larger share of federal taxes. In 2020, for example, households in the highest income quintile received about 56 percent of all income and paid 81 percent of federal taxes.

But income inequality is a runaway train, you might say. On the contrary, any serious investigation shows that the pre-tax income of the top 1 percent in America has been roughly flat for twenty years. Counting after-tax income instead, as a share of total income the super-rich today lay claim to about the same share (9 percent) they did in the 1960s. In the UK, income inequality is the same today as when Thatcher left office, and globally speaking inequality is probably lower than it’s been in 150 years.

But for whatever ideological reason, maybe you want the rich to be eaten. Well, the hungry behemoth that is the US federal government is already eating the rich, yet its stewards and proponents want ever more. It’s not just that government spending has exploded out of control at least since the pandemic, but in the last five years tax revenue as a share of GDP has increased in almost all rich countries, from France and the UK to South Korea and the US. And the American tax system is already almost unbelievably progressive.

Like an unstoppable Pacman, the world’s governments keep eating.

It’s not even that easy to (painlessly!) commandeer the abundant wealth the rich supposedly have.

Even If You Want It, The Rich Don’t Have Your Money

The rich aren’t rich because they stole your stuff and hoarded it, like some mythical dragon. Mostly, they’re rich because they built a thriving business that made all (or at least a lot) of us better off, and we, in the form of market returns, rewarded them handsomely for that creation. In Bureaucracy, one of Mises’ lesser-known works, the roles of consumers and entrepreneurs are quite clear: “the real bosses, in the capitalist system of market economy, are the consumers.” By their very actions of buying certain goods over others, consumers “decide who should own the capital and run the plants.”

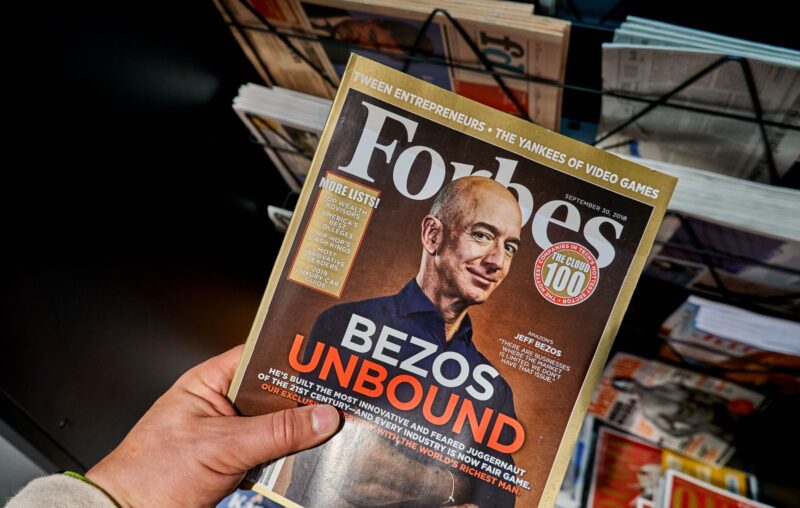

Jeff Bezos or Elon Musk aren’t ultrarich because they chose to be (though they may have), worked hard (which they verifiably did), or stole their wealth from someone else (which they didn’t). They’re rich because consumers rewarded them with purchases and because financial markets priced their respective company shares accordingly.

Whatever your opinion on Amazon’s effect on local commerce or its labor conditions — to say nothing of Tesla’s pretty ruthless use of taxpayer subsidies — it’s undeniable that their companies have provided cheaper and better goods to many, many people.

Most people in my generation think about wealth as a pile of money, stashed away in a bank vault or the basement of some outrageous mansion. Instead, wealth largely consists of ownership in productive businesses that make the world run (and, overwhelmingly, real estate, which is even more hopeless to expropriate and redistribute).

And it’s not that easy to just “take it,” even abstracting away all the political or legal hurdles to expropriating Americans’ private property.

Dismantling companies to give their “value” back to the deserving poor — many of whom will lose their jobs in said companies in the process — seems like a bad idea, since you’ll destroy that value. For large, publicly traded companies, we do have some neatly divisible spoils in the form of shares. Per the SEC, Bezos owns some nine percent of Amazon, or 938,251,817 shares in total.

Nobody needs that much, say the billionaires’ critics confidently, so we righteously confiscate 900 million of those, worth about $158 billion at the time of writing. 166 days into this Fiscal Year, the Treasury has spent 2,684,154,624,114 dollars — almost 3 trillion, comfortably on its way to a proposed $7.2 trillion for the year — a neat $23 billion a day. At face market value, Bezos’ great fortune would finance the government for… less than a week.

Except that it won’t even do that.

The minute we announce this expropriation, the price of AMZN — and all other similar companies we may or may not confiscate in the future — falls like a rock. No buyers. What we’ll raise from this insane play amounts to much less than the face value of the stocks the day before.

Let’s keep making fantastical wishes and assume that it didn’t — maybe all investors agree that this policy is necessary, and nobody is troubled by it — as we sell the shares to finance spending (or hand them out to the 100 million or so poorest Americans who, in turn, sell them instead), we’re mechanically crashing the price of AMZN shares. Ordinarily, Nasdaq trades about 46 million Amazon shares a day and since only a small portion of that is net buying (index funds, brokers, intraday trading etc), it would take us months to offload our 900 million in spoils. Realistically, we’d net a much smaller amount from our sophisticated heist.

If we do this bright and early on a Monday morning, when Sunday comes around we’re once again broke, assuming of course that we acquired the full market value. Does anyone think we can repeat the trick next week? Surely, all the other potential targets saw what we just did, and have been busy moving to Singapore or London or the Bahamas, transferring their ownership to offshore entities, or otherwise shielding them in nonprofits or any number of other defensive measures to ensure that the proceeds from the next billionaire we go after will be much, much lower.

We expropriated (“ate”) the top-2 richest American and aside from financial market chaos, all we got for it was financial support for the bottom third of Americans equivalent to one round of stimmies — plus a whole lot of disincentives to live, work, create, invest, or incorporate in America. What we achieve is a one-time transfer from the ultrarich to the poor, and permanent damage to the very economic goose that laid America’s abundance of golden eggs.

So…Don’t Take It?

If the rich are rich because they provided the rest of us with a lot of value through the businesses they built, we want the rich to be richer still — not poorer. The rich aren’t rich enough.

If we wish to expropriate their riches for our allegedly benevolent ends, we’ll need much more than their current riches to move the needle. The rich aren’t rich enough.

Taxing the rich truly is a lunatic’s solution to our fiscal headaches — a nightmarish one at that.

Instead of trying to orchestrate a costly and not-that-fruitful reshuffling of the pie, perhaps we should just leave the rich to keep expanding it — for their sake, for our sake, and ultimately for the peace of the republic.

Or, formulated as the “Bourgeois Deal” by Deirdre McCloskey’s and Art Carden’s condensed version of McCloskey’s three-part Bourgeois masterpiece — Leave me alone and I’ll make you rich.