Debt or Taxes

Back in January the first annual work programme of the new European Commission was published. The programme had a significant focus on taxation initiatives relating to climate change and digital transition, but the longer-term ambition to harmonise tax rates across the EU27 remains a distant goal.

The EU’s Finance Ministers established the Code of Conduct Group (Business Taxation) in March 1998. Under the code, the criteria for identifying potentially harmful measures included: –

- An effective level of taxation which is significantly lower than the general level of taxation in the country concerned

- Tax benefits reserved for non-residents

- Tax incentives for activities which are isolated from the domestic economy and therefore have no impact on the national tax base

- Granting of tax advantages even in the absence of any real economic activity

- The basis of profit determination for companies in a multinational group departs from internationally accepted rules, in particular those approved by the OECD

- Lack of transparency

The OECD took up the cause of tax harmonisation more than two decades ago, establishing a Forum on Harmful Tax Practices in 1998. The current work of the Forum focuses on three key areas: –

- The assessment of preferential tax regimes to identify features of such regimes that can facilitate base erosion and profit shifting, and therefore have the potential to unfairly impact the tax base of other jurisdictions

- The peer review and monitoring of the Action 5 transparency framework through the compulsory spontaneous exchange of relevant information on taxpayer-specific rulings which, in the absence of such information exchange, could give rise to BEPS concerns

- The review of substantial activities requirements in no or only nominal tax jurisdictions to ensure a level playing field

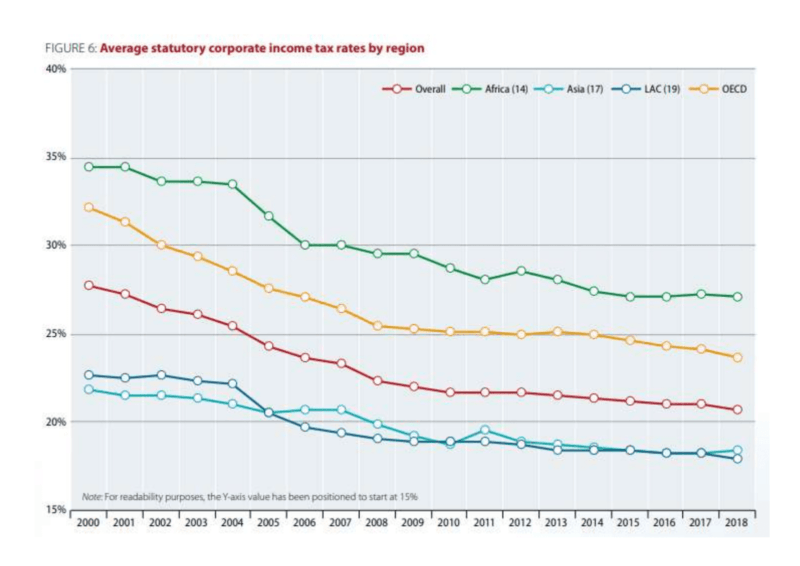

Despite their best efforts, little progress has been made towards tax harmonisation. The ECIPE Occasional Paper – Unintended and Undesired Consequences: The Impact of OECD Pillar I and II Proposals – published in April, gives an excellent overview of the current state of affairs. They note that governments, globally, have been lowering statutory and effective corporate tax rates for nearly four decades, through a mixture of special tax incentives, the introduction of special economic zones and incentives for research and development.

This competitive race to the bottom is at odds with the OECD Pillar I and Pillar II aims to curb international corporate tax competition: –

Pillar I aims to design new rules for the (re)allocation of taxing rights between jurisdictions. It considers several new mechanisms for profit allocation and new nexus rules. Pillar I proposals are framed as a policy remedy to corporate income that is currently not taxed in the countries where it is generated. Recent proposals indicate that the new rules under Pillar I go beyond digital companies, i.e. they will affect more companies in more industries.

Pillar II (also referred to as the “Global Anti-Base Erosion” or “GloBE” or “Minimum Tax” proposal) aims to design a new set of rules for a minimum taxation of corporate income. It is framed as an attempt to address “ongoing risks” from corporate structures that allow multinational enterprises to shift profits to jurisdictions where they are subject to no or low taxation. Rules resulting from Pillar II would provide (high-tax) jurisdictions with a right to “tax back” where (low-tax) jurisdictions have not exercised their primary taxing rights or the payment is otherwise subject to low levels of effective taxation.

The OECD reforms are designed to reduce ‘corporate tax avoidance’ and ‘unfairness in taxation.’ The OECD estimates that harmonisation will increase tax revenues by up to $100bln, which will be evenly distributed across 137 countries. Despite the potential windfall, most governments have largely ignored requests for the release of information about their individual impact assessments. One reason why more open economies have failed to cooperate is because the proposed reforms would shift tax sovereignty and economic activity away from smaller economies towards larger, higher tax, countries. The implementation of the OECD proposals would lead to a fiscal transfer away from governments that embrace freer trade. Foreign direct investment (FDI) for smaller economies would fall; meanwhile, larger, less open countries would maintain their trade barriers. Businesses would be forced to relocate to larger economies, and consumers would suffer.

The OECD claims that their proposals will improve the global allocation of capital, but the lack of tax competition will almost certainly have the opposite effect, stifling innovation in the process. ECIPE goes on to propose the somewhat radical idea that policymakers abolish corporate taxes altogether, taxing individual income from labour, capital and consumption instead.

Personally, I am in favour of tax harmonisation via competition. A city or state should have the power to set tax rates in order to attract businesses and individuals. Despite attempts to harmonise higher, globalisation, even during the last two decades, has seen corporate tax rates trend lower: –

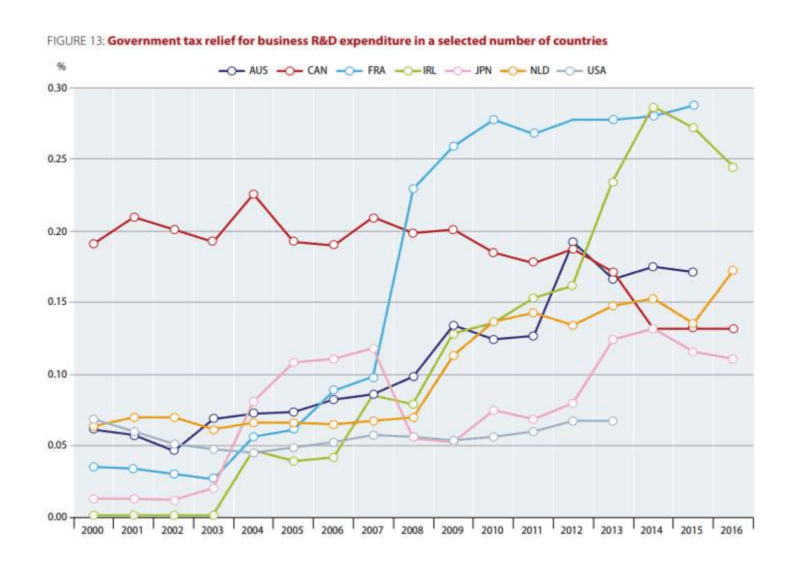

Even in countries where headline corporate taxes may have remained high, there have been incentives such as R&D allowances: –

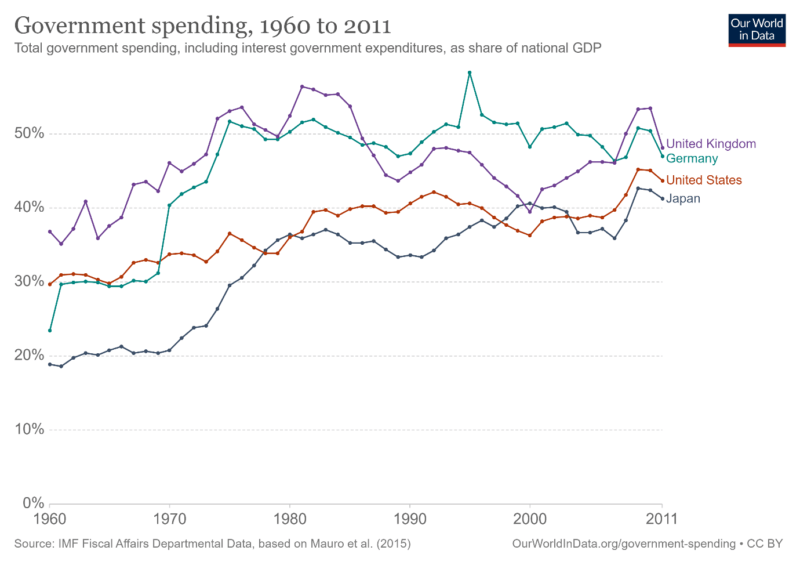

The trend towards lower taxation has risen, even as the absolute amount of government spending has increased. The chart below shows the evolution of government spending to GDP since 1960: –

Trend Acceleration

The Covid-19 pandemic has led to the acceleration of many economic and social trends. Technology stocks have risen, remote working has become a permanent affair for millions, global supply chains have shortened; the list of trends accelerated grows longer by the day. The competition for taxpayers is no exception.

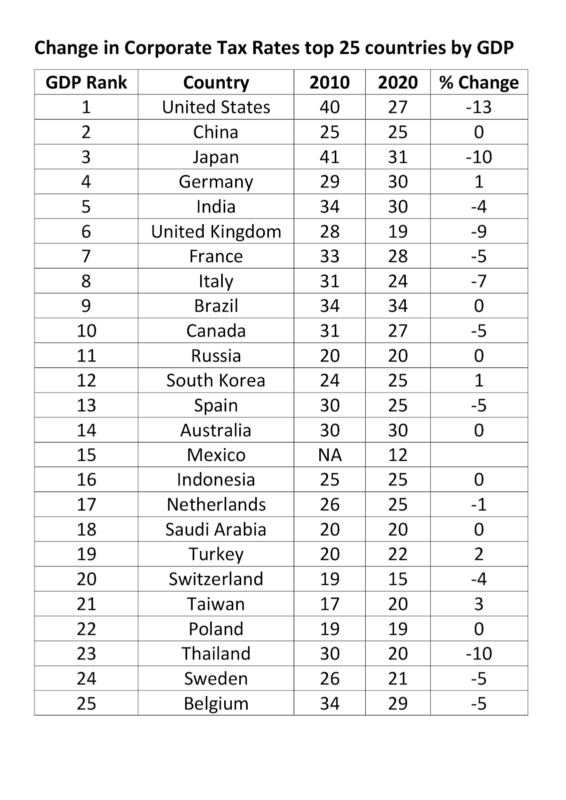

The table below tracks the change in corporate tax rates of the 25 largest economies over the past decade: –

Around the globe there are 37 countries with corporate tax rates of 15% or less – ten of which levy no corporate tax at all. Within Europe, countries such as Portugal have enticed the wealthy with ‘Golden Visas,’ although this has reignited their property bubble and may soon be curtailed. Now Italy has joined the contest, offering up to 90% relief on worldwide earnings for individuals who relocate to some of the less affluent regions of the country. France is considering Eur 20bln of tax cuts to encourage corporations to establish production in their country. Andorra, Cyprus, Malta and Monaco continue to offer very favourable terms, together with more or less unfettered EU access. As remote working has become the norm, thousands of small businesses are beginning to take flight. Competition among tax domiciles seems certain to increase.

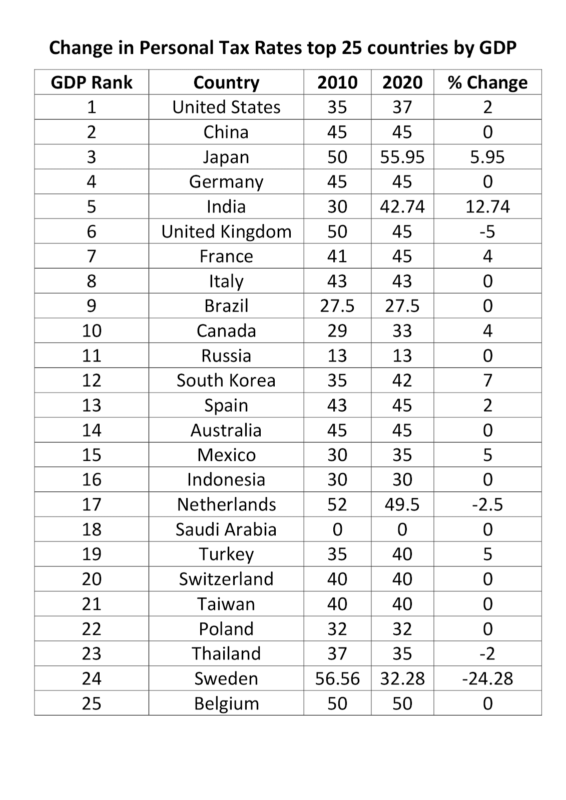

By contrast to corporate tax, personal tax rates have not seen so much change over the last ten years: –

This lack of reduction in individual tax rates between countries is partly a function of immigration policy. Corporate domiciles can be switched with relative ease; a change of personal domicile is more challenging.

Within many countries, taxation varies from region to region. In the US, for example, tax rates change from state to state, but the long reach of the US tax authorities means the state where your primary residence is located may tax your income no matter from where in the world it is derived. Meanwhile, any state where you earn revenue also has the right to tax you on that income. Caveat emptor.

Notwithstanding the potential double-dipping of the tax authorities, the trend toward self-employment among skilled workers seems destined to accelerate. Along with that transformation, an increasing number of individuals will move their corporate entities to the most tax-efficient domicile. Technological progress and greater global integration have been a boon for workers with the right skills in expanding industry sectors. The expected slowdown in the global economy makes job prospects over the next two years look dim, but the pace and depth of the digital transformation is likely to be startling. We may see high rates of unemployment and skill shortages simultaneously. This infographic from the OECD Employment Outlook 2019 outlines some of the major thematic shifts in the nature of work globally: –

If governments cannot rely on corporate taxes, they have three options: reduce expenditure, increase personal taxation or issue more debt. With the future of work looking increasingly uncertain and the entrepreneurial classes heading for the most efficient tax domicile, debt is the obvious and least painful solution, especially with long-term interest rates at or near the lowest level in history.

During the past month, Bank of England Governor Andrew Bailey has indicated that negative interest rates are firmly in their toolbox. Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell, announced a more flexible approach to their 2% inflation target; whilst the ECB has let it be known that it is due to review its bond-buying programme at its next meeting. Albeit, the more hawkish members of the board are muttering about the legality of continued accommodation. All these moves (more or less) lend support to the view that interest rates will remain low, quantitative and qualitative easing will expand and any uptick in inflation will be not just tolerated but practically welcomed.

The total outstanding stock of negative-yielding government bonds hit an all-time high in the summer of 2019, but, as the chart below reveals, we are getting close to the peak once more: –

Among the top 25 countries by GDP, Switzerland has the lowest borrowing costs. Ten-year maturity Confederation bonds yield -0.50% whilst 50-year bonds yield -0.38%. Germany comes next at -0.50% for 10-year and -0.06% for 30-year paper. Of the large Eurozone economies, Italy pays the most; its 10-year bonds yield 0.85%, whilst it has to pay 2.01% to borrow for 50 years.

Outside of the Eurozone, Japan can borrow for 40 years at 0.60%, the UK for 50 years at 0.61%. Borrowing costs for the US (1.43% for 30 years) and China (3.11% for 10 years) look relatively expensive by comparison, but, with a second wave of Covid-19 sweeping across Europe, fears are that the rest of the world will follow. Near-term expectations of a strong global economic rebound, together with any inflationary pressure that might conceivably ignite, remain slim.

At the present juncture, developed country government bond yields are more likely to fall than rise. Fiscal spending will be financed by deferred taxation, the repayment of today’s (and probably tomorrow’s) obligations will be bequeathed to our children and grandchildren. Digital taxes, taxation on wealth and financial transaction fees may creep higher at the margins, along with higher taxes on higher earners, but debt is the least painful solution to the fiscal needs of the present.