A Technological Revolution in Education

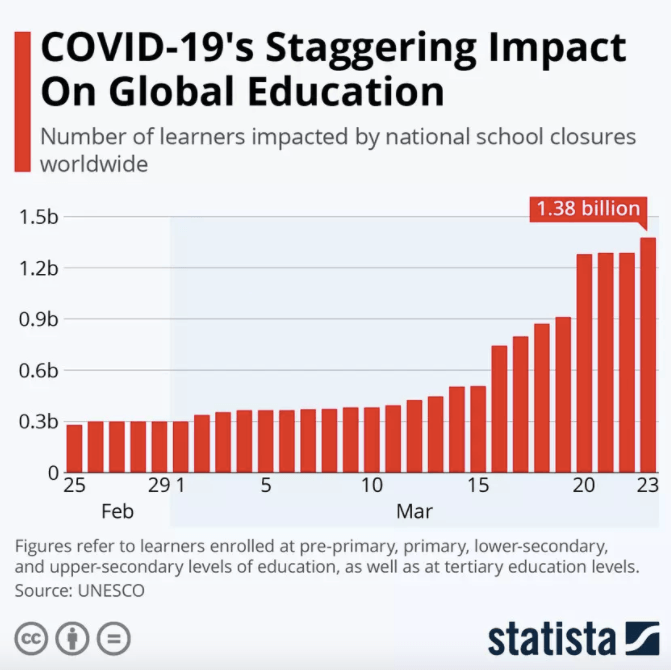

As the world adjusts to the new COVID order, education, like so many other sectors of the global economy, has been shaken from its technological torpor by the need to deliver products remotely and cost effectively. The virus has resulted in more than 1.38bln students (approximately 90% of the total) across 185 countries being shut out of classrooms: –

Education is an industry which has been ripe for change, yet the technologies, which should have allowed it to slip the surly bonds of Earth, have lain practically dormant for more than two decades.

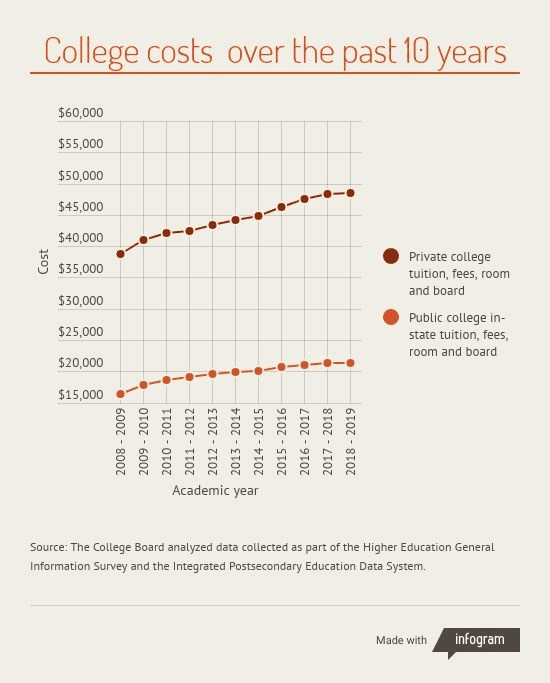

The economic need for catharsis is patently clear, as this 2019 chart, tracking the rising cost of US college fees reveals: –

On average US tuition costs have risen 37% over the ten years to 2019, whilst average earnings have only risen by around 20%. The differential has been absorbed by a ballooning of student debt which, at $1.6trln, now amounts to the largest tranche of personal, non-housing, debt.

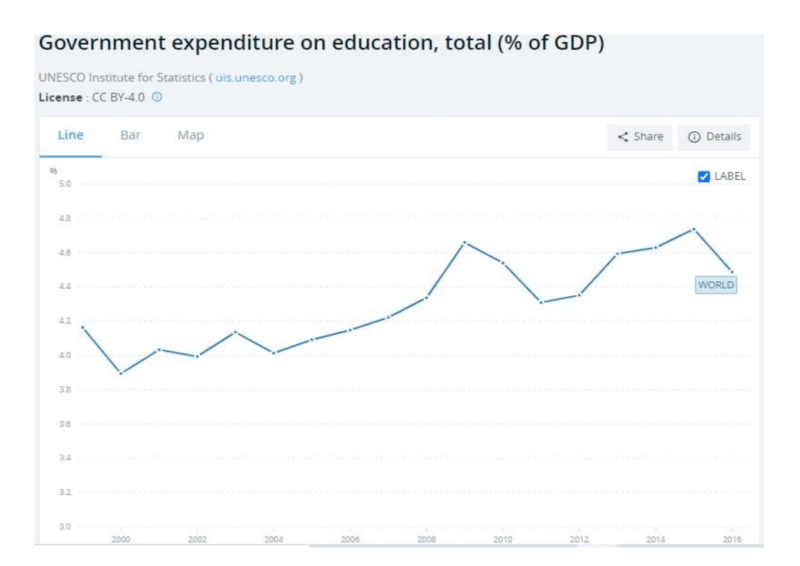

Expenditure on education is neither an individual nor a simply US phenomenon; it is a large percentage of both government expenditure and global GDP: –

Given that global GDP was estimated to be $142trln in 2019 (Statistica), that puts state spending on education at around $6.3trln/annum.

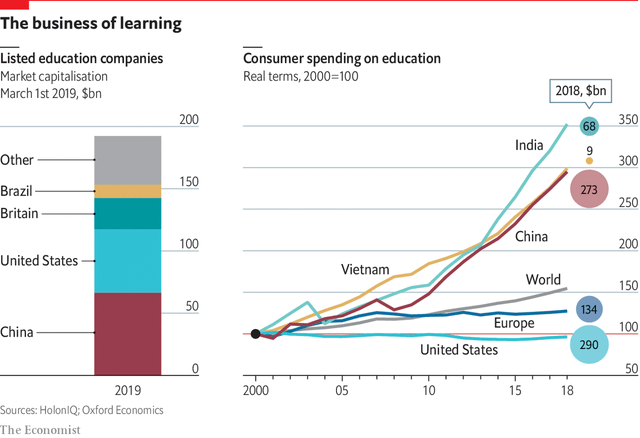

Public education represents the lion’s share of the education market but the private sector ($774bln according to The Economist estimate below, from 2018) is not insignificant. Despite rising costs, private school enrollment has risen, by 10-17% at primary level and by 19-27% at secondary level, since 2005: –

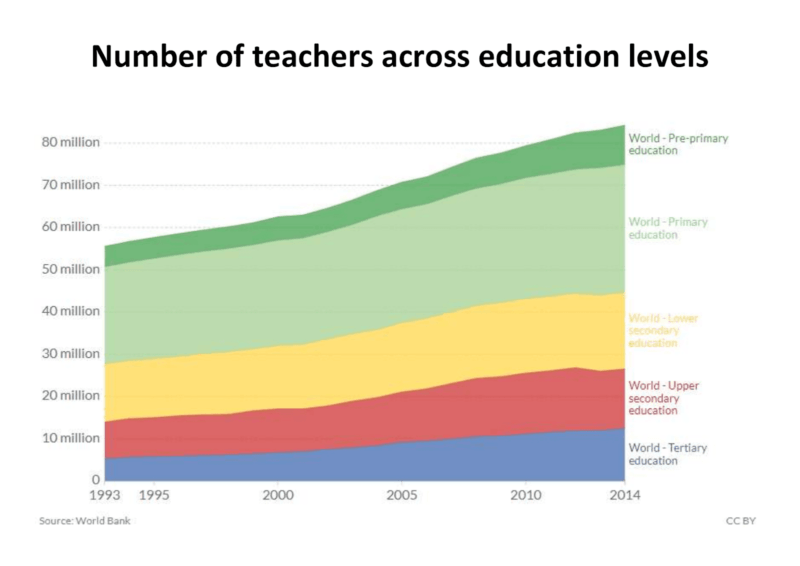

The education sector also represents a substantial proportion of global employment, as this 2015 infographic from the World Bank shows: –

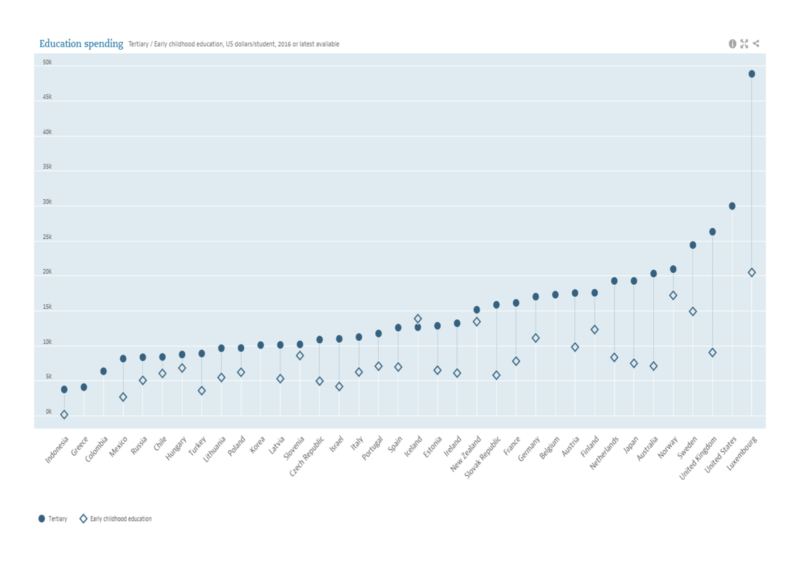

For individual governments, educational expenditure varies greatly. It also varies between the primary and tertiary sector as this next chart reveals: –

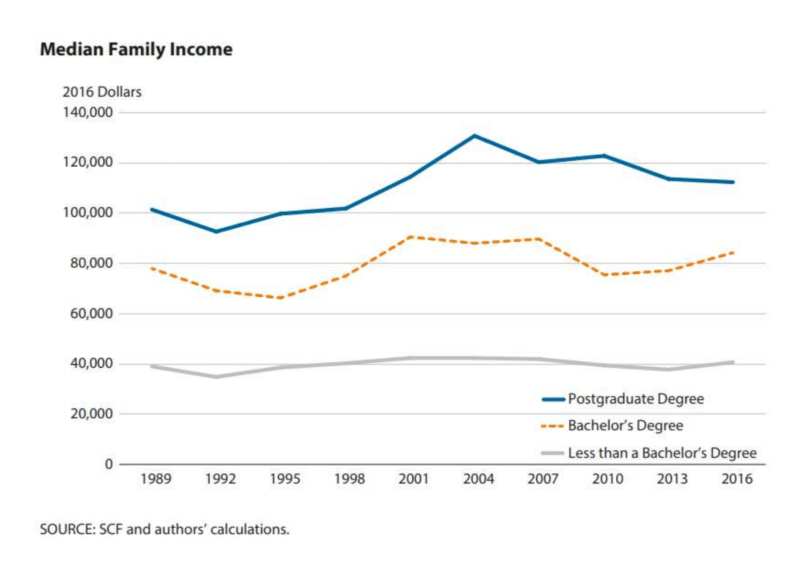

In the US, University enrollment continues to grow; it reached almost 20mln in Q4, 2019. The Federal Reserve analysed the value of tertiary education in 2014 and their St Louis branch revisited the topic last Fall in – Is College Still Worth It? The chart below shows the evolution of the educational earnings premium over the period since 1988: –

The chart is misleading in that it fails to highlight the generational differences between cohorts. For recent graduates the differential income between a postgraduate and a Bachelor’s degree has narrowed significantly. Nonetheless, the income enhancing benefits of tertiary education continue to support the economic logic of acquiring a Bachelor’s degree.

School’s Out

Since March, education globally has been forced online. This has benefitted wealthier families over poorer ones and developed countries over developing nations. Even in the affluent US, it is estimated, by the US Department of Education, that one in eight children do not have adequate internet access. Meanwhile, according to OECD data, whilst 95% of Austrian, Norwegian and Swiss students have access to a computer, that figure falls to a mere 34% in Indonesia. Remote learning also requires far more self-direction and intrinsic motivation than is required in a physical classroom. Once again this favours the more affluent household.

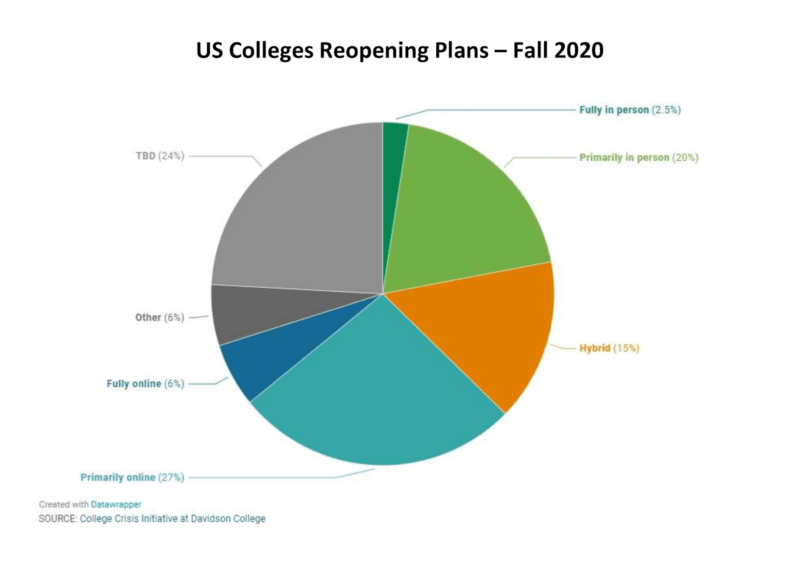

As the Fall of 2020 arrives The Chronicle of Higher Education reports (August 22nd update) that only 22.5% of colleges intend to offer classes fully or primarily in person: –

More importantly, 27% of the sample (3,000 institutions) intend to deliver education primarily online.

Many of these institutions need to improve their online performance. According to a One Class survey, conducted in April, 75% of students were unhappy with the quality of eLearning during the early stages of the pandemic.

Conversely, however, when eLearning is effectively delivered it can enhance productivity dramatically. A recent Brandon-Hall Study showed that eLearning typically requires 40% to 60% less time, while the Research Institute of America found that eLearning increases retention rates by 25% to 60%. There are other studies which are less favourably disposed towards eLearning, but these examples reveal the nascent potential benefits.

An excellent and more balanced discussion of the pros and cons of global educational response to the pandemic is provided by this Brookings Institution interview. Nonetheless, from a technological perspective, the infographic below neatly outlines some of the additional benefits of online education: –

For those institutions which are failing to meet eLearning expectations, the economic consequences may be dire. Whilst a number of students have asked for fee rebates due to the lack of service, others have brought lawsuits and a further 35% are considering voting with their feet and moving to lower cost, more technologically savvy institutions. Best College Reviews provides a useful list of eLearning platforms, many of which offer free courses. The list is US-centric and around the world the number of EdTech providers is growing rapidly.

Having taken five free MOOCs (Mass Open Online Courses) in the last few years, I can attest to the variability of quality. The economic puzzle is that, whilst much of the technology (such as the video recording of lectures) has been available for almost forty years and the internet has been ubiquitous since the mid-1990’s, the pandemic has revealed the negligible investment made by the majority of educational establishments in labour saving, cost reducing, experience enhancing technology.

As in many areas of the global economy, the pandemic has accelerated the pace of structural economic trends. Nowhere is this feature more evident than in technology and EdTech is no exception. Recent research by Metaari indicates that EdTech investment is finally beginning to accelerate, reaching $18.66bln in 2019. If ResearchandMarkets forecast proves accurate, however, capital investment will need to turn exponential to reach $350bln by 2025.

We have seen evidence that eLearning allows for quicker delivery and higher retention, but are there other benefits? The Tech Advocate makes a number of additional observations.

Firstly, costly books and printed materials can be saved and delivered online. These resources are then instantly redistributable, globally. Not only are students able to save on the cost of acquiring resources but teachers are able to focus on teaching rather than being encumbered with the administrative burden of preparing resources.

A second EdTech benefit for students and teachers alike is the ability of technology to make the teacher’s role more flexible. Rather than having to teach a class of students at, or near to, the pace of the slowest learner, EdTech allows a larger proportion of students, within the same class, to learn at their own pace. In this way, larger classes can potentially be taught or greater teaching resources can be devoted to the individual coaching of students of all abilities.

Conclusion

The global pandemic has affected a permanent change to the delivery of education. Whilst younger children, and those from poorer backgrounds are clearly suffering from the lack of structure created by the closure of schools, for many parents, the increased level of engagement with their children’s education has been profound, if not wholly positive, as this article from Vox explains. Educational technology at primary and secondary level can help to deliver better engagement between teachers and students together with their parents or guardians. At the tertiary level, where students are expected to study independently, engagement can also be enhanced.

In productivity terms, technology should allow the quality of education to be improved and the cost of delivery reduced. A much greater number of students can, theoretically, be educated with the same human resources. The absolute amount of streaming by students based on their learning abilities can be reduced. It may even be conceivable that larger class sizes can be taught without a detrimental impact on quality, although this is a topic of fierce debate.

UNESCO’s 2030 agenda, signed in May 2015, includes SGD4 (sustainable development goal 4) which aims to: –

…ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all.

Here is a link to the Education 2030 document, for any readers who would like to find out more about UNESCO’s aspirations.

EdTech is by no means the answer to every challenge faced by educators globally, but it has the potential to make a much greater difference than we have seen in the last twenty years. The COVID pandemic is a global tragedy, but necessity is the mother of invention. As we have seen elsewhere, technology is the solution to a wide array of today’s challenges. Many of the solutions required by educators globally are already in place; they simply require judicious adoption.

I want to finish with an anecdote. Back in 2015, I studied an online course in finance. The course consisted of 16 weeks study over two semesters. It was brilliantly presented and included a continuous and ever more challenging series of finance problems, finishing with a two-hour examination. There were students from around the world, but one stood out from the crowd. He was a Maasai tribesman from Kenya, a farmer. His objective, in enrolling in the course, was to better understand micro-finance. This is just one example of the potential for the combination of technology and education to empower us all.