When Politicians Say Fair Tax, They Only Mean More Tax

Politicians never seem to have much trouble telling us they want to raise taxes. It seems to come as naturally to them as breathing does to the rest of us. They do their level best to keep the spotlight on “the rich,” of course, who they say must “pay their fair share.” But what do politicians hardly ever say? They hardly ever say who “the rich” are. And when they do, they usually point to multibillionaires while meaning people with considerably less. What do they also never say? They never say what a “fair share” is. It really just means “more.” Who would’ve thought.

This leaves a problem for the class warfare class, because it is these same rich people who fund their political campaigns. And as if that weren’t bad enough, most Congressmen and Senators are rich themselves. The two who yell the loudest about taxing the rich, Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren, are worth $2.5 million and $12 million respectively. What are the odds that these two, and all their cronies in Congress, would bite the hands that feed them? What are the odds they would bite their own hands?

We do well to remember 1988. George H. W. Bush, in accepting the Republican nomination for the presidency made his point perfectly clear. People would pressure him to raise taxes, but when that happened he would say, he claimed, “Read my lips. No new taxes.” All things considered, that’s a pretty easy promise to make, but a much harder promise to keep. It wasn’t long before Bush broke his promise, but in doing so he only went after “the rich,” signing into law a 10 percent luxury tax on things rich people buy – yachts, private planes, and expensive jewelry.

The tax was supposed to raise more than $30 million in additional revenue, but it didn’t raise much of anything. The rich simply went elsewhere to purchase their luxuries. Entrepreneurs and the working class paid, and they paid dearly as the tax destroyed almost 10,000 jobs in the boating, aircraft, and jewelry industries. Meanwhile, foreign companies in these industries made out like bandits. And that’s the difference between the rhetoric and the reality of taxation.

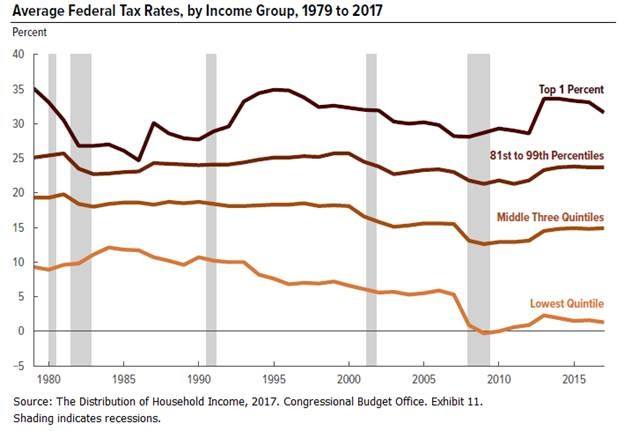

We can dig deeper still into tax reality through the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), which asks Americans how much they earn and how much they pay in federal taxes. Breaking down those answers by income level provides some valuable insight into who is and isn’t paying their “fair share.”

To sidestep technical problems like write-offs and deductions, wages versus interest income, and payroll versus capital gains taxes, the CBO lumps together into a single pile all the federal taxes people actually pay: income taxes (net of the Earned Income Tax Credit), payroll taxes, corporate taxes (including capital gains taxes), and excise taxes. Into another pile, the CBO places the market income people earn from all sources: wages, salaries, employer-paid benefits, interest income, business income, capital gains, rental income, deferred income, and other sources of non-governmental income. CBO then divides the first number by the second to get people’s average effective tax rates. The average effective tax rate is the fraction of people’s total incomes that they actually pay to the IRS.

The CBO’s latest numbers don’t tell us what is fair; but they do tell us who is paying what. While politicians avoid this the way vampires avoid garlic, knowing what people actually pay is the first thing we need to determine in any discussion of what’s “fair.”

In 2017 (the last year for which data is available), average household income among the top 1% was $2 million, average household income among the middle 20% was $61,700, and among the bottom 20% was $15,900. After the various accounting and legal gymnastics one goes through to reduce one’s tax burden, the average household among the top 1% paid around 32% of that $2 million in federal taxes. The average middle-income household paid 17%, and the average household among the bottom 20% paid less than 2%.

In other words, the average one-percenter household earned about 125 times what the average bottom 20-percenter household earned, but paid over 2,000 times the federal taxes.

And this isn’t a new phenomenon. The rich have been paying the lion’s share of federal taxes for decades. In fact, since the mid-1980s, the average effective tax rate paid by the top 1% has remained about the same while the rate for the bottom 20% has steadily declined.

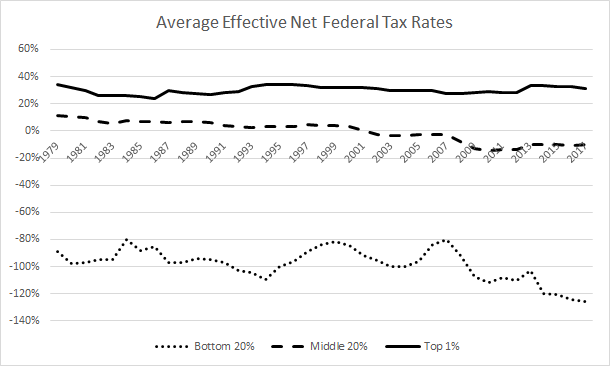

But this isn’t the entire story, because while the federal government takes with one hand, it gives with the other. Transfers are cash payments and in-kind services the government gives to people. Means-tested transfers are distributed on the basis of need and typically fall as a household’s income rises. Earnings-tested transfers are distributed on the basis of earnings and typically rise as a household’s income rises.

The government provides means-tested transfers through Medicaid, CHIP (Children’s Health Insurance Program), SNAP (formerly “food stamps”), Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (formerly Aid to Families With Dependent Children), housing assistance, income assistance, energy assistance, and child nutrition programs. It provides earnings-tested transfers in the form of social insurance benefits: Social Security and Medicare benefits, unemployment insurance, and workers’ compensation.

Workers tend to think of social insurance benefits – particularly Social Security retirement benefits – not as government transfers but as a return on money they paid into the social insurance system. In fact, the Supreme Court long ago established that Social Security benefits are not a contractual right (Fleming v. Nestor, 1960), and that Social Security taxes paid into the system are like any other government revenue and not earmarked for Social Security benefits (Helvering v. Davis, 1937). Consequently, in our calculations, we should treat social insurance payroll taxes as any other federal tax and, similarly, social insurance benefits as any other federal transfer.

Clearly, these transfers are largely things the government does to help lower income households. But regardless of the intention, the transfers are, in fact, negative taxes. Subtracting transfers households receive from the taxes households pay yields net federal taxes paid. The average household among the top 1% paid $620,000 in federal taxes and received $1,300 in transfers on $2 million in market income, for an effective net tax rate of 31%. The average middle-income household paid $10,500 and received $16,800 on market income of $61,700 for an effective net tax rate of negative 10%. The average household among the bottom 20% paid $300 in taxes and received $20,300 in transfers on $15,900 in market income for an effective net tax rate of negative 126%.

One interested in taxing the rich to give to the poor can argue that this sort of outcome is precisely the sort of thing a progressive tax system is supposed to achieve. Putting aside the argument as to whether massive transfers like this are advisable, what is clear is that it’s a bit of a stretch to claim that the rich aren’t paying their “fair share” when the bottom 60% of households aren’t paying anything at all.

Accounting for both federal taxes and federal transfers, on average, only the top 40 percent of households are net payers into the federal tax and transfer system. This is why most discussions about tax cuts end with the charge that the side proposing tax cuts merely wants “tax cuts for the rich.” Our system of taxes and transfers is so progressive that, almost by definition, every tax cut is a tax cut for the rich because, on average, those are the only households that are net payers.

In a democracy, a tax system in which some are net payers and others are net recipients becomes dangerously unstable when the net recipients constitute more than half of all voters. At that point, the majority have an incentive to vote for ever more spending for themselves and ever more taxes on the minority who pay.

None of this is new, because it’s not about our particular economic or political systems, but about human nature. People always want more in exchange for less. Politicians have merely discovered a way to turn people’s desire for more into votes for themselves. The trick is to tell the voting majority that the rich minority isn’t paying its fair share, and that if only the voting majority would cast their votes correctly, fairness can be restored. By never defining “fair,” though, politicians can just repeat their tiresome claims election after election.

So what exactly is anyone’s “fair share?” That’s a hard question, and it’s made harder still when people tasked with answering it do everything they can to avoid answering it. As long as this continues, calls for the rich to pay “their fair share” will never end because, in light of the numbers, proponents seem not to mean “fair” at all. They simply mean, “more.”