Minimum Wage: Fact Checking the Fact Checking

Many media sources provide fact checking of claims made by presidential candidates in televised debates. But sometimes you need to read that fact checking carefully.

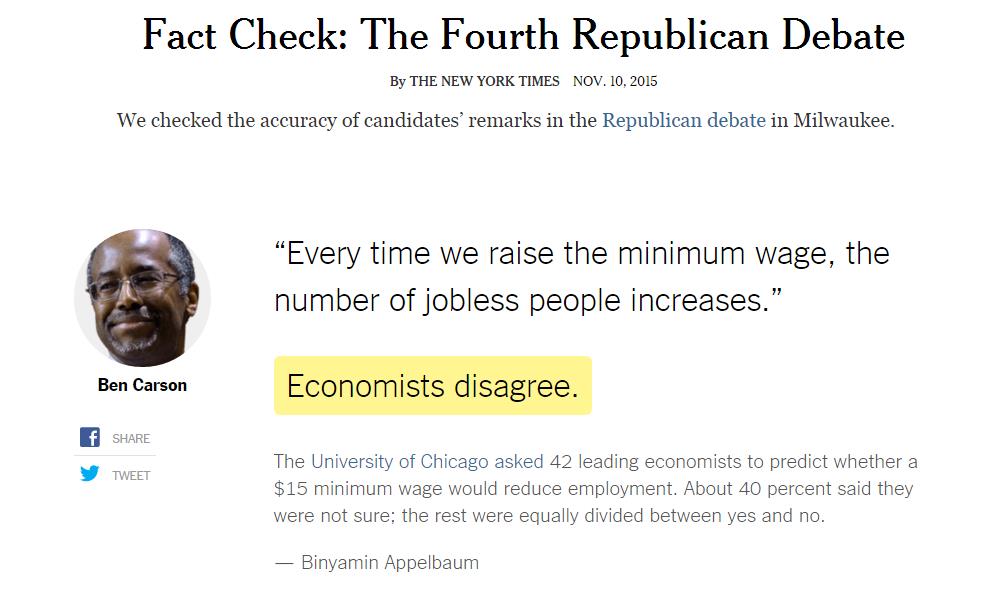

Here is an example (a screenshot of a part of an article from The New York Times):

It might seem straightforward, but it is not.

So, the claim is that the number of jobless people increases after the minimum wage is raised. Every word here is important. It is the number of jobless people, not the unemployment rate. It is possible for the number of jobless people to increase even if the unemployment rate is unchanged – because the population and the labor force grow over time.

The response of the New York Times is that economists disagree with this claim. But the evidence presented to support this response actually shows something quite different. It shows that, according to the survey by the University of Chicago, about 40 percent of economists are not sure, and the remaining 60 percent are about equally split between yes and no. In other words, only about 30 percent of economists think that increasing the minimum wage to $15 (this is what the survey asked) would not hurt employment. I would call it “SOME economists disagree.”

Why do economists seem to be so unsure about the effect of raising the minimum wage?

To understand this, it would help to look at the actual survey that the University of Chicago performed (the link was also provided in the Times article). Because this is a survey of economists designed by economists, their question was very specific:

The respondents were asked to agree or disagree with the following statement:

If the federal minimum wage is raised gradually to $15-per-hour by 2020, the employment rate for low-wage U.S. workers will be substantially lower than it would be under the status quo.

Note that we are talking about raising the minimum wage to $15 per hour gradually by 2020, and the question is whether it will substantially reduce the employment rate of low-wage U.S. workers. The word “substantially” is crucial in this question.

The economists responding to this survey have an option of including comments with their response. Not all did in this case, but many of those who did talked about “substantially.” For example, Richard Schmalensee from MIT noted “Lower, probably; substantially lower, not clear at all.” Barry Eichengreen of Berkeley said, “Empirical studies disagree on the sign of the effect. Few of those concluding in favor of negative are consistent with ‘substantially.'”

By the way, both of them disagreed with the statement, so they were counted by the New York Times as being among those who do not think that higher minimum wage increases the number of jobless people. But in reality, they only disagreed that it will substantially reduce employment, but they would be quite comfortable with saying that it would reduce employment less than substantially.

This might seem like nit-picking at every word, but it actually reveals the heart of the disagreement about the effects of a minimum wage increase. It is the magnitude of the effect that economists disagree on, not its direction.

To make this clear, consider an extreme and unrealistic example – what would happen if the minimum wage was raised to $100 an hour? Every economist would answer this question by saying employment would fall and the number of jobless people would rise. This is because such a huge increase in the minimum wage would make labor extremely costly to businesses, and they would find a way to economize on the use of labor (that’s economist-speak for “employ fewer people”).

There is no disagreement in the economic profession that making labor costlier gives businesses an incentive to use less labor. The direction of this incentive (use less labor) is clear, it’s the magnitude of it that is in question.

This is because adjusting the number of workers a business employs is not that simple. People are not pound of cement – you can only lay off one worker, not 0.2 of a worker, for example. In some cases, the functions performed by people can be replaced by equipment, but since equipment is expensive, it only makes sense to do that when labor costs increase quite a bit. Moreover, laying off employees, or replacing them with machines, has other undesirable effects (it is not good for the morale of the remaining employees, among other things).

If we raise the minimum wage just a little – say, by $0.10 an hour – would companies look for ways to shed employees? Probably not, as the negative effects of losing workers outweighs the miniscule increase in their cost. But if the minimum wage is raised a lot – to $100 an hour, or even “just” to $30 an hour – the negative effects of losing workers are no longer large enough to justify such a huge increase in labor costs, and companies would definitely reduce employment.

Then the all-important question becomes – how high can we raise the minimum wage before it starts having a negative effect on employment? We do not have the answer to this question.

Why not? Because the only way we, economists, can study the effects of some change, like an increase in minimum wage, is to look at the instances of it in the past. And all the past increases in the minimum wage were small — much smaller than the proposed increase from $7.25 currently to $15. All past increases in minimum wage were definitely under a dollar (see chart), a far cry from the almost $8-increase contemplated.

It is difficult to use our knowledge, which was derived from studying small increases in minimum wage, to predict the effect of a large increase in minimum wage, especially because we have good reasons to believe that employers respond differently to large change in labor costs than they do to small ones.

Many respondents to that survey by the University of Chicago pointed this out, indicating that a change to $15-an-hour is larger than anything previously observed:

“Low levels of minimum wage do not have significant negative employment effects, but the effects likely increase for higher levels.” – Daron Acemoglu, MIT

“The total increase is so big that I’m not sure previous studies tell us very much.” – Erik Maskin, Harvard

“Our elasticity estimates provide only local information about labor demand functions, giving little insight into such a large increase.” – Larry Samuelson, Yale

“For small changes in min wage, there are small changes in employment. But this is a big change.” – Christopher Udry, Yale

So, is this true that raising a minimum wage increases the number of jobless people? Probably.

Does this happen because companies fire employees? Not necessarily – they may just be hiring less than they would have otherwise.

Does this mean that the employment rate falls? Not necessarily, or not by much. But even if the employment rate stays the same (say 95 percent of people who want a job have one – i.e. the unemployment rate is 5 percent), the number of jobless people would still be rising over time (because the population and the labor force grow over time).

Does this mean that raising the minimum wage is always a bad idea? It depends (the favorite answer of economists to most any question). It depends on what one is trying to achieve by raising the minimum wage.

For example, if the minimum wage hike leads to a very small decrease in employment, but an increase in income of low-income segments of the population, some may see that as a desirable outcome. The point here is that it is important to be clear about what you consider to be a desirable outcome.

There is no free lunch and an increase in minimum wage can have negative consequences for employment. So, to argue in favor of it, one has to be clear about what positive consequences it will have and that they are large enough to outweigh the negative ones.