Your Right to Absinthe

You can’t believe the shock. I was sitting in a living room drinking absinthe with friends, and I said in passing something like:

“This is delicious but wouldn’t it be great if the original recipe with wormwood were legal again?”

My friend, the economist George Selgin, said; “This has wormwood in it just like the absinthe from the old days!”

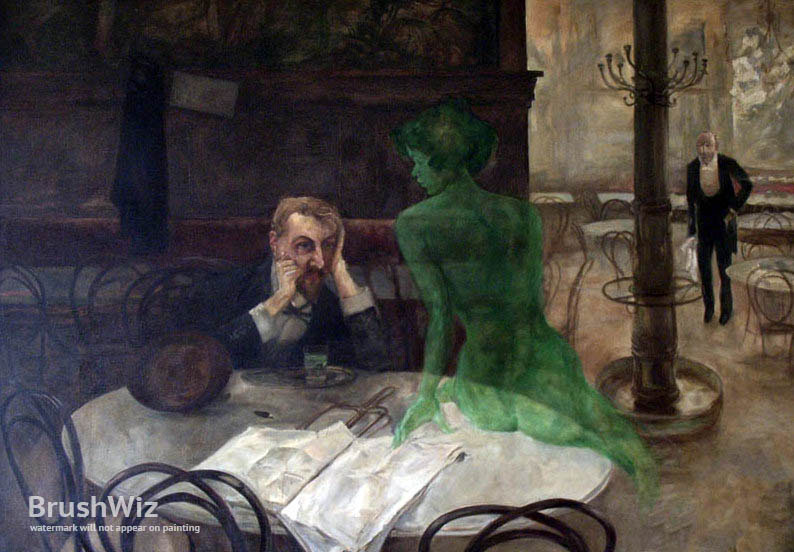

I grabbed the bottle and looked at the ingredients. Sure enough, he was right! Printed right on the label was the word. Then I became worried that something terrible or wonderful was about to happen to me, that I would see green fairies, hallucinate that I was floating, and maybe cut off my ear.

It turns out that I was the victim of a 100-year old moral panic about wormwood that has absolutely no basis in fact at all. Wormwood has been used as a medicinal herb since the ancient world, and there is a great deal of legend surrounding the stuff, but there is zero evidence that it has any hallucinogenic properties at all!

What about the belief that it was banned? It was indeed banned, over most of the Western world since the late 19th century. But get this (which you probably already know but I did not): it was relegalized for import into the United States in 2007. Now there are micro-distilleries all over the country that make the real thing, the exact drink about which Oscar Wilde wrote:

After the first glass of absinthe you see things as you wish they were. After the second you see them as they are not. Finally you see things as they really are, and that is the most horrible thing in the world. I mean disassociated. Take a top hat. You think you see it as it really is. But you don’t because you associate it with other things and ideas. If you had never heard of one before, and suddenly saw it alone, you’d be frightened, or you’d laugh. That is the effect absinthe has, and that is why it drives men mad. Three nights I sat up all night drinking absinthe, and thinking that I was singularly clear-headed and sane. The waiter came in and began watering the sawdust.The most wonderful flowers, tulips, lilies and roses, sprang up, and made a garden in the cafe. “Don’t you see them?” I said to him. “Mais non, monsieur, il n’y a rien.”

Kind of makes you want to go out and buy a bottle right now. Fortunately you can, because your right to drink the stuff has been restored. The century-old moral panic is over. However, with that change, some of the cachet has been drained away from this yummy drink, which, as it turns out, is just a drink like any other: if you drink too much, you get drunk. Nothing special here.

The irony of the history here is that it was precisely the dire warnings, first issued in French medical journals in the mid 19th century, that created the vast demand for absinthe all over Europe and America. Dangerous drink? Bring it on. The British medical journals seemed to agree that absinthe was highly dangerous, citing this strange experiment from 1869:

The question whether absinthe exerts any special action other than that of alcohol in general, has been revived by some experiments by MM. Magnan and Bouchereau in France. These gentlemen placed a guinea-pig under a glass case with a saucer full of essence of wormwood (which is one of the flavouring matters of absinthe) by his side. Another guinea-pig was similarly shut up with a saucer full of pure alcohol. A cat and a rabbit were respectively enclosed along with a saucer each full of wormwood. The three animals which inhaled the vapours of wormwood experienced, first, excitement, and then epileptiform convulsions. The guinea-pig which merely breathed the fumes of alcohol, first became lively, then simply drunk. Upon these facts it is sought to establish the conclusion that the effects of excessive absinthe drinking are seriously different from those of ordinary alcoholic intemperance.

Whoo hoo! You can imagine, then, why that generation of artists, poets, playwrights, and literary gadabouts immediately seized on this drink and caused it to be the most fashionable in the land, spreading the plague of absinthism far and wide. Paintings, poetry, music were written in homage to the great muse of the green fairy. No doubt that people believed it, just as Dumbo thought it was the feather that made him fly.

At the height of the absinthe mania in France, 5:00pm became known as “the green hour.” The french were drinking 5 times as much absinthe as wine. The French producers were shipping all over the world. It became the world’s most notorious drink.

Here we have a classic case: science speaks of danger, daring people jump on the trend, moralists get outraged, government acts. That is precisely the situation that lasted for 100 years until it became rather obvious that absinthe is just a normal liquor.

The reason it gained the reputation for making people insane – Vincent Van Gogh, for example – is that highly fashionable people were drinking far too much of the stuff. It was a classic fallacy: post hoc ergo propter hoc. A confusion of cause and effect. That was enough to effect a century of prohibition.

Here is another medical journal from 1873 about the vast multitudes of “victims of absinthe.”

Originally the only important ingredient in its composition, besides alcohol, was the essential oil of absinthium, or wormwood; and though, doubtless, this added something to the mischievous effects of the liquor, it would be impossible to trace to it, or to the other comparatively trivial ingredients, the more serious of the special results which are now observed to occur in the victims of absinthe. An analysis recently made at the Conservatoire des Arts shows that the absinthe now contains a large proportion of antimony, a poison which cannot fail to add largely to the irritant effects necessarily produced on the alimentary canal and the liver by constant doses of a concentrated alcoholic liquid. As at present constituted, therefore, and especially when drunk in the disastrous excess now common in Paris, and taken frequently upon an empty stomach, absinthe forms a chronic poison of almost unequalled virulence, both as an irritant to the stomach and bowels, and also as a destroyer of the nervous system.

Science has spoken. What can you do but ban it? That didn’t happen until 1915 (the same few years in which every terrible trend in politics happened, from income taxation to central banking). By then, the drink became associated with elaborate rituals that survive to this day, such as the slow-drip fountain that pours over a special steel spoon that holds a sugar cube. So far as I can tell, the ritual is entirely for show (if you want a bit of sweet in your drink, just add simple syrup) but it’s also enormously fun to reenact the faux-decadence of the absinthe generation. Even now, Amazon offers many absinthe fountains, most in the Victorian style of course.

Bans stemming from moral panics never seem to end, and people never seem to learn from this classic example. But in this case, glory be, the bans gradually came to an end. We’ve lived a full twelve years of absinthe freedom. And sure enough, with that freedom has come a bit of blase attitude toward it. When I ordered it last night, the bartender had to hunt for 10 minutes to find the bottle.

There is surely another lesson here. My own prediction is that once marijuana becomes universally decriminalized it will at that moment become far less fashionable than it has been for 40 years.

It’s my habit, and maybe it should be yours, to celebrate every bit of freedom we gain back from the armies of authoritarians who wield the power of the state to improve our lives. It took one hundred years, but they finally got their mitts off this one market.

To me, this merits a visit from the green fairy as soon as possible. Raise that glass to the freedom to choose, even to hallucinate.