Transfer Payments Tend to Discourage Labor Force Participation

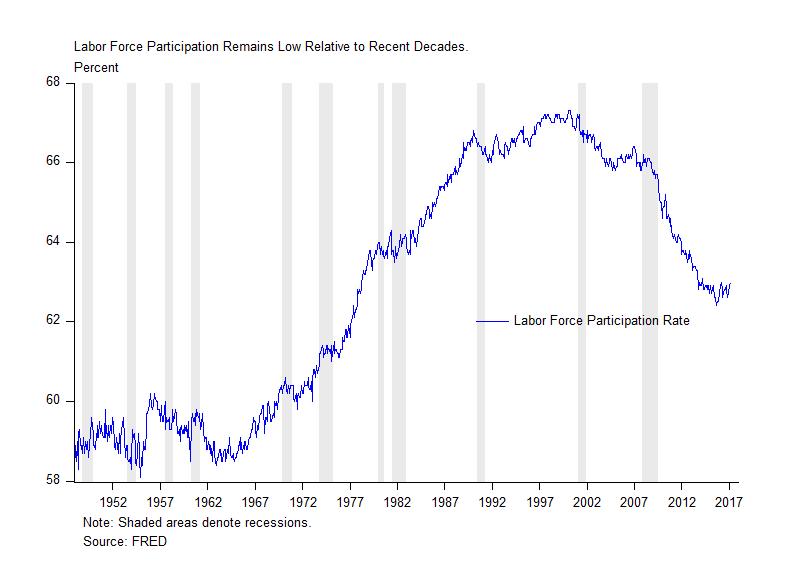

The labor force participation rate began a gradual decline after peaking in the spring of 2000. If the decline is to be reversed, we may need to reassess federal transfer payments that exacerbate the ongoing trend.

As the dot-com crash and 2001 recession took hold, the rate was nearly 67 percent. During the economic expansion between 2002 and 2007 the rate fell slightly to 66 percent. During the Great Recession and subsequent weak economic recovery, the rate has continued to decline. Today it is 63 percent.

The labor force participation rate is calculated as the labor force divided by the working-age population. To be counted in the labor force a person must be either employed or unemployed and have looked for work in the past four weeks.

What explains the decline in labor force participation? There are cyclical and structural reasons. Cyclical forces are fluctuations in the business cycle. The two most recent economic recoveries have been weak by historical standards. The economy struggled to recover after Federal Reserve–induced bubbles burst, first in tech then in housing. Weak economic recoveries have kept some people out of the labor force.

Structural forces go beyond fluctuations in the business cycle. Structural declines in the labor force have been driven by demographics. Baby boomers have been retiring, driving down labor force participation. According to the CBO, by the middle of the 21st century, labor force participation is expected to fall to nearly 59 percent. Members of subsequent generations, who are replacing baby boomers in the labor force, tend to participate in the labor force at lower rates.

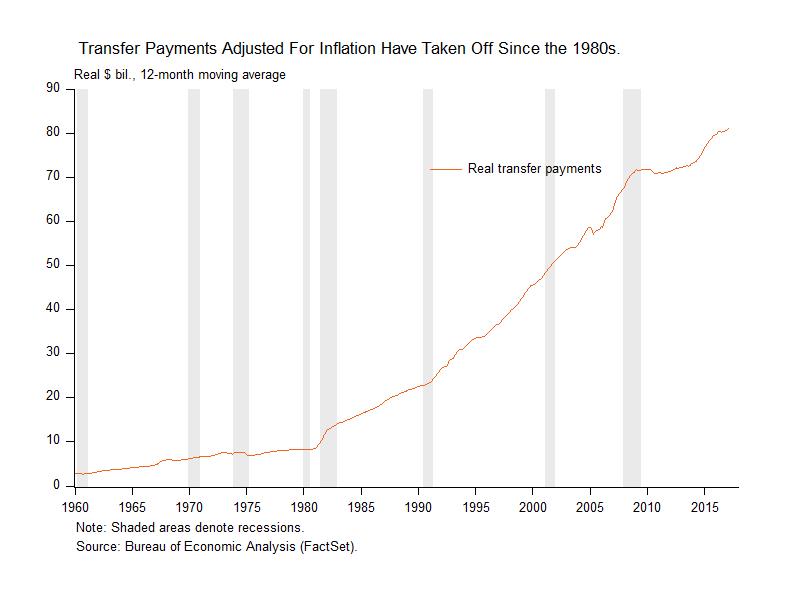

The federal government has attempted to soften the blow of a lower cyclical and structural participation rate. Instead of helping, the federal government has implemented policies that have exacerbated the decline in the participation rate.

Transfer payments from the federal government tend to discourage labor force participation. The share of people receiving disability-insurance benefits is projected to continue increasing, and people who receive such benefits are less likely to participate in the labor force. Disability benefits and food stamps are quickly phased out if a non-worker takes a job. The phase-out means a higher tax rate on work. On the margin, each hour of work actually means less money in the bank.

This leaves the economy with fewer people seeking work and therefore less production, lower tax revenue, and a larger federal deficit and debt. With the federal government debt near an all-time high, transfer payments that discourage labor force participation need to be addressed. Transfer payments need to encourage work and lift people up, not keep them at home.