Is “Sustainable Fish” Real or a Marketing Ploy?

I was out shopping for some swim trunks for a hotel stay and the only ones I could find were from a “sustainable” clothing store. A store with a philosophy. I couldn’t imagine what the merits of a sustainable pair of swim trunks would be but I bought them anyway.

For all I know, it’s a sales gimmick (I was in Northern California, hint hint) but so long as the proprietor is making money and giving me cool things in return, I’m all about it. I just adore how capitalism can turn any movement, even goofy lefty ones, into profit opportunities, which is why I don’t begrudge any business any marketing edge.

The next day, it was time to sample food from Fisherman’s Wharf (that the name survives in this hyper-PC area of the country is something of a wonder). Every restaurant claimed to sell fish that was both local and sustainable. The local part I get because I love the idea of chomping on seafood dragged off boats right here that just returned from the sea just over there. Local in this case is wonderful whereas I really don’t care, for example, if my potatoes are grown locally.

But what is sustainable fish? I looked down at the yummy piece of cod on my plate and it looked dead as can be, certainly not sustainable. In our hyper political times, even those of us that try to avoid thinking about politics can be triggered by this kind of messaging. So my first instinct was to roll my eyes and mutter about the absurd profligacy of the sustainable label.

Just another overused linguistic fashion.

As it turns out, I was so wrong!

The sustainable label does in fact mean something. It is enforced by no government. It is a purely private certification that addresses an actual problem and caters to the voracious desire on the part of contemporary consumers for information on the food they buy.

If oceans and other bodies of water were entirely private, true, there would be every incentive to make sure stocks of fish were replenished and bycatch (waste) was minimized as with every other private enterprise. Forestry or any other form of agriculture are good case studies. Depleting everything in one season would be disastrous for business, so it would be discouraged and efficiency would rule.

Which is to say: sustainability is built into market forces.

But privatization is not the rule, so the fishing industry faces the tragedy of the commons, an incentive for waste to deplete as much as possible before the other guy does it.

It became obvious decades ago that sustainability in fishing was becoming a serious problem. As the World Wildlife Fund writes:

Fishing is one of the most significant drivers of declines in ocean wildlife populations. Catching fish is not inherently bad for the ocean, except for when vessels catch fish faster than stocks can replenish, something called overfishing.

The number of overfished stocks globally has tripled in half a century and today fully one-third of the world’s assessed fisheries are currently pushed beyond their biological limits, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

Overfishing is closely tied to bycatch—the capture of unwanted sea life while fishing for a different species. This, too, is a serious marine threat that causes the needless loss of billions of fish, along with hundreds of thousands of sea turtles and cetaceans.

The damage done by overfishing goes beyond the marine environment. Billions of people rely on fish for protein, and fishing is the principal livelihood for millions of people around the world.

Many people who make a living catching, selling, and buying fish are working to improve how the world manages and conserves ocean resources.

What, then, is the solution in lieu of some implausible shift toward privatizing oceans? The answer is private controls enforced through reputation. How does this work in practice?

Let’s look at the case in point.

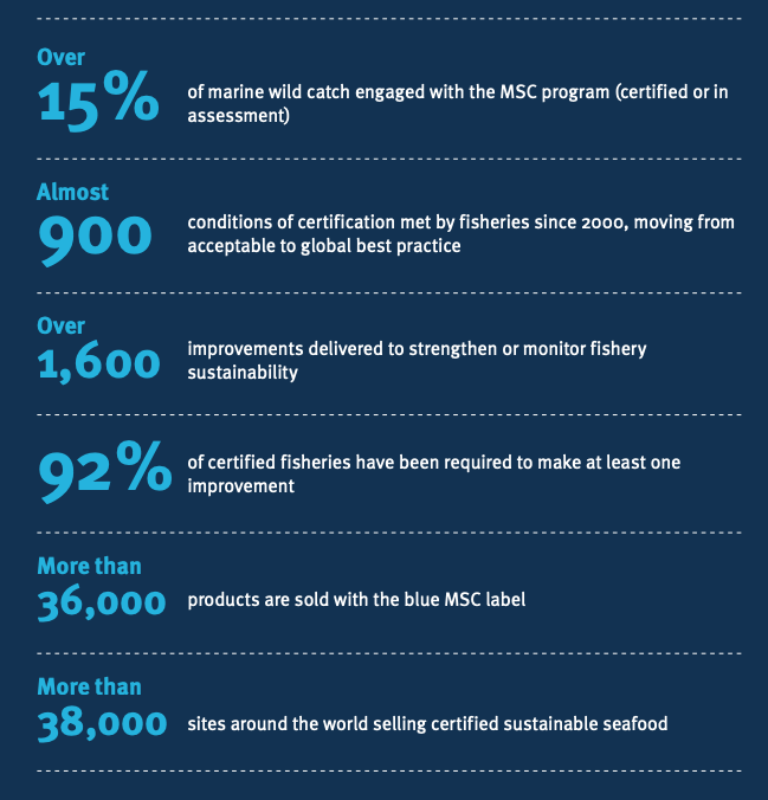

In the 1990s, a new organization came to be called the Marine Stewardship Council. It’s a completely private organization that developed scientific standards for measuring whether or not a certain fishery is practicing their craft in a way that does not deplete the fish population and does minimize waste in terms of bycatch, and also shows respect for the environmental integrity of the body of water they use. They have a stamp of approval called sustainable that can be used by fisheries and restaurants and stores that can demonstrate a clear supply chain link back to the fishery.

The Council is funded by dues, and payments for audits, which can range between $15K and $100K depending on the size. The designation has to be renewed every five years. Those fisheries that earn the label can then use it in marketing their product. Consumers are on board with this because no one really wants to eat food that comes at the expense of the health of both the environment and the future of the industry.

The Council, born of a collaboration between environmentalists and businesses, now has offices around the world and stays constantly busy certifying and monitoring fisheries.

From ocean to plate, MSC -certified seafood is tracked, kept separate from non-certified products, and is clearly labeled so it can be traced back to a certified sustainable source. Every company at every step of the supply chain must be certified and audited annually to ensure these strict rules are adhered to.

What happens if a fishery loses the designation? Grocery stores like Whole Foods will simply stop buying. That hurts the bottom line. No ideological agitation is required: sustainability is in the economic interests of everyone. And this kind of activity actually overcomes the problem of the commons. It’s an example of the brilliant way that private action can manage environmental problems without recourse to legislation, central planning, and coercion.

What to do to prevent corruption and payoffs? How can we be sure that the Council is not gaming the results? The Council itself uses a third party audit of fisheries to stop that. Further, they are in turn policed by other environmental groups. Greenpeace for example has variously disputed some of the Council’s judgments. They hash it out in the court of public opinion and arrive at a compromise position — in a way that requires no government oversight or badgering or compulsion.

Which is to say this is another case of Edward Stringham’s private governance. The results are made public for the world to see.

Look, this is just one case. But it reveals how private action can actually solve problems in society without government. Let the market figure things out. It turns out that people are pretty darn creative and consumers quite responsive, so long as bureaucracy doesn’t get in the way. What’s more, this is a solution that most intellectuals would never have considered.

So, yes, I’ve stopped rolling my eyes at the label sustainable. It’s real and it matters. And it shows how markets work even when the odds are against them.

What other problems are considered to be insoluble that we need to turn over to the creative forces of society itself? Whatever the issue – sustainable environment, climate change, racial and gender inequities, poverty, access to health care – turning the cause over to government is the path least likely to succeed. Creative market-based solutions generated from within the matrix of exchange and choice lead to real solutions.

That said, I’m still not sure what it means for swim trunks to be sustainable. They did survive the first washing, so that’s a good sign. In light of my new knowledge concerning fish, I’m all ears.