The Turkish Currency Crisis and What It Can Teach Us

Turkey’s currency turmoil follows a well-known scenario. It is one more case in the long series of financial crises that afflict the international monetary system. Just over the past two-and-half-decades, international markets experienced the crisis of the British pound (1992), the Mexican and Argentinean currency crises (1994), the East Asia currency turmoil (1997), and the collapse of the Brazilian currency (1999).

In 2007, the liquidity-driven housing boom in the United States began to falter and Lehman Brothers filed for bankruptcy threatening the global financial system. In 2009, the Greek debt troubles started as the overture to the European financial crisis of 2010. The European Central Bank and the International Monetary Fund bailed out the troubled countries with Greece receiving several packages that ended in 2018 without a significant recovery of its economy.

Now it is Turkey’s turn. The dispute about an American citizen as a religious prisoner in Turkey, a tweet by the American President about higher tariffs on imports from Turkey, and the Turkish Lira spiraled into a hefty devaluation.

After some recuperation after the severe losses which the Turkish Lira suffered in the first wave of the sell-off in early August, the currency’s value sank again against the US-dollar and the euro thereafter. Since January 2018, Turkey’s currency devalued from around 3.5 Turkish Lira per dollar to almost seven Turkish Lira per dollar at its peak in August 2018 (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Exchange rate of the Turkish currency (Turkish Lira per US-dollar)

\Since 2010, the balance sheet of the Turkish central bank has more than tripled. This expansion came as the result of putting an end to the independence of the Turkish central bank by Turkey’s president Recep Tayyip Erdogan. He was democratically elected in 2014 and re-elected in 2018. Over the years since he took power, he has become increasingly authoritarian to the dismay of his Western allies, including the United States.

Turkey is just one more example of the many emerging economies whose leaderships have put their countries on a splurge of debt. Over the past ten years, emerging market dollar debt has more than doubled. The extremely low interest rates of the dollar, the euro, and the yen attracted many governments in the emerging economies to borrow in foreign currencies. There are many candidates which will have to confront external debt problems when interest rates in the United States and Europe should continue to rise.

No Plan

As a response to the currency crisis, the Turkish president did not come up with a solid economic policy plan, which would include a cut in government spending and curbing the money supply. He rather accused ‘foreign powers’ for the mess, with the American President as the prime culprit of his accusations. Instead of signaling economic policies which could stabilize the currency, president Erdogan denounced the fall of the Turkish currency as an ‘enemy attack’ on his country. This reaction of the Turkish president has contributed to a further loss of the value of the Turkish currency.

The devaluation of the currency means that Turkey’s debt burden has doubled in terms of its domestic currency. At the end of the first quarter of 2018, Turkey’s foreign debt amounted to 466.7 billion US-dollars or 55 percent of Turkey’s gross domestic product. While the overall ratio of public debt to the gross domestic product is relatively low, almost 50 percent of the public debt is in foreign currency, which makes the budget vulnerable to a currency devaluation and the stoppages of international capital inflows.

The reduction of the relative burden of public debt was mainly due to a good growth performance over the past decade. After a swift recovery from the international debt crisis of 2008, the annual real growth rate of Turkey’s gross domestic product averaged around seven percent. In the first quarter of 2018, the annual growth rate reached 7.4 percent after 7.3 percent in the quarter before. This spectacular performance is now in jeopardy.

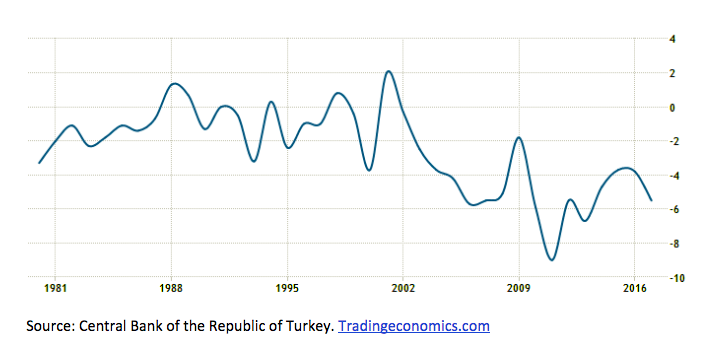

Even if Turkey can avoid an outright default, the economic impact of the sharp currency devaluation with the consequent rise of the interest rate will reduce investments and squeeze profits. As a consequence, unemployment will rise. The Turkish consumers will face rising prices and higher unemployment. The price inflation rate already stands at 16 percent and is two times higher than the mean of the ten years before (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Turkey. Price inflation rate (annual percent)

President Erdogan’s government has lost the confidence of the international investors when the president undermined the formal independence of the Turkish central bank after he took office. At the beginning of his new term, president Erdogan practiced outright nepotism when he appointed his son-in-law as treasury and finance minister in June 2018 right after his re-election.

Turkey’s foreign debt exposure results from the country’s persistent current account deficits as these require the import of capital. With the decline of the Turkish lira, it will become harder to finance these deficits. From 1980 to 2017, the current account balance was on average at -2.5 percent. Since 2001, the country has experienced a sharp deterioration, and the deficit hit nine percent in 2011. After some recuperation to about four percent in 2014, the current account deficit widened again and stands at 5.5 percent in 2017 (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Turkey. Current account balance in percent of the gross domestic product

Since 2002, first as prime minister and since 2014 as president, Erdogan has intensified his grip on the country and abolished civil liberties. The failed 2016 coup has given him a free hand to intensify the authoritarian style of his rule. Erdogan challenges what has defined modern Turkey since the end of the sultanate. As president, Erdogan has moved to authoritarianism driven by religious zeal. He thus represents a break with Turkey’s modern history.

Erdogan’s new mandate extends until 2023. He can act freely based on the new institutional framework of an ‘Executive Presidency’, which gives him broad legal authority over almost all governmental activities, a privilege he won after winning the referendum to his favor of a new presidential system for Turkey.

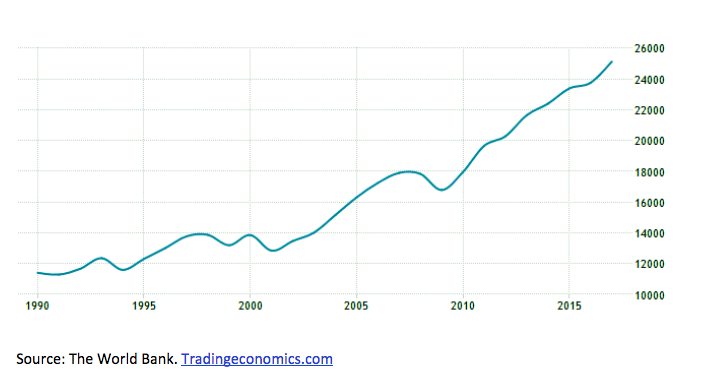

With a better economic management, Turkey would have the chances to become a wealthy country. It has a diversified economic structure. Turkey’s domestic financial system is flexible and resilient. Over the past decades, Turkey has experienced remarkable economic progress. Since the beginning of the new millennium, the economy has registered high growth rates with a moderate price inflation. Over the past two decades, the purchasing power per capita has almost doubled (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Turkey. Gross domestic product per capita in purchasing power parity (in US-dollar)

President Erdogan’s aspirations to establish an Islam-based authoritarianism and his erratic, incoherent, and nepotistic economic policy puts Turkey’s progress at risk. The crucial reforms of the Turkish economy were made before he came to power. Erdogan could enjoy the favorable economic situation prepared by his predecessors and gain the laurels while in fact he has been on the path to destroy not only what was accomplished in the decade before his rule but since the 1920s.

After the end of the Ottoman Empire, Turkey became a republic in 1923. Since then, the country has become one of the most secular countries in the Middle East. Under the leadership of Mustafa Kemal Pasha, later called Atatürk (father of the Turkish people), Turkey experienced a profound and broad transformation.

After Atatürk’s death in 1938, the subsequent leaders continued Turkey’s path to modernization. In 1952, Turkey joined the NATO, became a founding member of the OECD in 1961, and an associate member of the European Economic Community in 1961. Yet the path to a modern economy and a democratic political system became stony thereafter. There were military coups d’état in 1960, 1971, and 1980, and a ‘military memorandum’ in 1997, which forced the ruling prime minister to resign.

With this intervention of 1997, the role of the military as a guardian of secularism has ended. Since then, Turkey has been exposed to a rising tide of re-Islamization. Erdogan is the catalyst in this development whose geopolitical implications are enormous. The Middle East is a powder keg and Turkey had been an important economic and political partner of the West. If the current crisis should deepen, and the split with the West should widen, Russia and China will try to get their share of influence.

Yet Turkey’s current crisis has more than one father. A country’s currency turmoil and foreign debt drama has many players and none of them is innocent. Although governments typically deny any own contribution to their country’s downfall, facts show that the outbreak of a debt crisis is the result of careless spending and incoherent economic policies.

Lenders have also their share to bear. International investors often lend despite better knowledge because they count on a bailout if things should go wrong. The governments and central banks in the creditor countries contribute their share because they provide the safety net and thereby originate moral hazard.

The International Monetary System

Besides these main actors – for debt accumulation to happen it takes two to tango and a band to play the music – there is also another factor at work that usually receives less attention: the international monetary system. Since the end of the gold standard, the international monetary system is without an anchor and subject to massive waves of liquidity expansion and contraction. When liquidity is rising, extended periods of current account imbalances occur, which, the longer they last, the harder they are to amend. When the correction happens, the adaptation is abrupt and harsh.

After the end of gold standard, currency crises are a recurring feature of the international monetary system. A functioning gold standard would do away with trade imbalances continuously. The deficit country would lose gold and would be forced to contract its money supply while the surplus country would experience the inflow of gold and a monetary expansion.

Through this mechanism, the price level would adjust and rectify surplus and deficit. So long as there is no new gold standard or at least one that would mimic its features, currency crisis will continue to happen. It would be a great illusion to believe that only low-income and middle-income countries could be the victims. It is only a matter of time when one of the big players is subject to a massive debt crisis.

The lesson to learn from the Turkish crisis does not only concern Turkey. It is one more crisis which calls for a reform of the international monetary system.