The Dangerous Path of Trump-Biden Trade Isolationism

The Trump administration began a trade war with multiple countries, indicating a concerning pivot towards a mercantilist trade policy that the current Biden administration has neglected to correct. It is a widely accepted economic idea that trade and open markets have greatly aided the prosperity of the United States as well as the rest of the world. Not only do they facilitate lower prices but they increase competition and innovation that benefits everyone from consumers to suppliers. There is also a moral element to free trade, which is that countries do not physically trade with each other, individuals within countries trade with each other. Trade balances and tariffs are not simply switches that our leaders can flip on and off; they represent the voluntary agreements that individuals around the world have with one another.

The benefits of a non-provocative trade stance are well known, which is why this article seeks to explore the damage to not only the economy but the global order that protectionist policies can create. To do so we do not need to look any further than our own Constitution as well as recent history, as the idea of free trade is a rather recent innovation.

Wisdom From the US Constitution

The US Constitution has a doctrine known as the Commerce Clause which Wex Law explains,

The Commerce Clause refers to Article 1, Section 8, Clause 3 of the U.S. Constitution, which gives Congress the power “to regulate commerce with foreign nations, and among the several states, and with the Indian tribes.”

Of course, there is much debate surrounding how much power the Commerce Clause actually grants Congress to regulate affairs among the states but that is unimportant for the context of this essay. From the explicitly written Commerce Clause, we get another doctrine known as the Dormant Commerce Clause. Wex Law explains,

“The “Dormant Commerce Clause” refers to the prohibition, implicit in the Commerce Clause, against states passing legislation that discriminates against or excessively burdens interstate commerce.”

Essentially, states could not impose their own tariffs or grant excessively burdensome monopolies that disadvantage firms operating outside the state. Although this is also a contentious topic because it is not expressly written in the Constitution, it was most famously articulated in Gibbons v Ogden, in which the Supreme Court struck down a New York State law that granted monopoly privileges to operators on its waterways.

One of the main justifications for such a decision was that tariffs and other state-granted privileges to domestic industries were essentially taxes on other states. The power to tax the states lies with the federal government and although there is no written prohibition on state-imposed tariffs, it is implicitly expressed by the Constitution. However, the Dormant Commerce Clause also has another rationale that is important to the idea of free trade. Wex Law explains,

“Of particular importance here, is the prevention of protectionist state policies that favor state citizens or businesses at the expense of non-citizens conducting business within that state. In West Lynn Creamery Inc. v. Healy, 512 U.S. 186 (1994), the Supreme Court struck down a Massachusetts state tax on milk products, as the tax impeded interstate commercial activity by discriminating against non-Massachusetts.”

The existence of the Dormant Commerce Clause fulfills an important objective of preventing trade wars within the states. That is because protectionism does not occur in a vacuum. If one state institutes trade protection, it will likely trigger a chain reaction of trade protections that bring interstate commerce to a halt and likely threaten the cohesion of the nation. Such a theory is not only rooted in common sense but the historical experience that the leaders of our country likely observed during the age of mercantilism.

The Logical Ends of Trade Protectionism

The basic insight that trade wars logically end in both sides imposing more and more restrictions on one another is a terrifying conclusion. The notion that a country should essentially maximize its exports and minimize imports to support its domestic growth is the general basis of a doctrine known as mercantilism.

Investopedia provides an explanation of this idea by writing,

“Mercantilism replaced the feudal economic system in Western Europe. At the time, England was the epicenter of the British Empire but had relatively few natural resources. To grow its wealth, England introduced fiscal policies that discouraged colonists from buying foreign products, while creating incentives to only buy British goods.”

Britain and Western Europe were forced to colonize the world and fight brutal wars over resources because free trade was absent. That is because if every country seeks to establish protectionist policies to support their own citizens, then oftentimes the only way to acquire resources is through military conquest, not mutual exchange.

Deirdre McCloskey notes in her book Historical Impromptus that in order for Britain to support itself under mercantilism it had to colonize about a quarter of the world. However, now under the relatively free trading regime that exists today, Britain is far richer than it used to be at only a shadow of its former size.

A more recent example of the danger of trade protectionism would be Imperial Japan and its quest for resources. Japan today is one of the freest economies in Asia and is a tremendously wealthy as well as an innovative country with few natural resources. It has greatly benefitted from the global adoption of free trade; however, that wasn’t the case back in the early 20th century. Lack of trade played an integral role in starting one of the bloodiest wars in human history as the Truman Library explains,

“Conflict in Asia began well before the official start of World War II. Seeking raw materials to fuel its growing industries, Japan invaded the Chinese province of Manchuria in 1931.”

The free exchange of resources and services greatly reduces the need for imperialist expansion and the risk of military incursions over valuable assets. Although protectionist policies may have good intentions, they inevitably lead other countries to do the same while oftentimes being counterproductive. The end result is a reality we should be frightened to return to.

A Disturbing Trend Towards Economic Populism

Despite the well-documented and gruesome history of economic populism, protectionism came back in vogue under the Trump administration. Disturbingly, this reactionary policy appears to be continuing under the Biden administration; Janet Yellen, Secretary of the Treasury, declined to remove tariffs on Chinese imports. Economic populists typically argue that barriers to foreign competition are in the nation’s best interest because it incentivizes firms to maintain domestic employment rather than outsourcing overseas. While the distributional effects of such policies can accomplish this – at least, in the short run – for specific industries, the consequences for domestic consumers and workers in the aggregate is overwhelmingly negative.

Beginning with the Trump administration’s trade war with China, which promised to restore steel manufacturing jobs, Prof. Irwin details at length the cumulative effects of such a trade policy. In an op-ed written for The Wall Street Journal, Irwin explains how the Trump regime saw trade as a zero-sum game. Accordingly, Trump railed against the North American Free Trade Agreement, imposed a 25% tariff on Chinese steel and aluminum, withdrew the U.S. from the Trans-Pacific Partnership, and threatened to leave the World Trade Organization.

The New York Times published the headline in March of 2018, “Trump Hates the Trade Deficit…” Ironically, due to Trump’s expansionary fiscal policy and Americans’ relatively inelastic demand for imports, the merchandise trade deficit was $864B in 2019 – exceeding 2016’s deficit by $100B. Evidently, tariffs did not close the trade deficit. U.S. tariffs were met by Chinese tariffs and Americans shifted to importing from other countries without tariffs. Tariffs were not solely paid for by China, but suffered by American consumers, workers, and employers.

In a memo to the Biden administration, Prof. Irwin explains the catastrophic outcome of Trump’s trade war:

“One study suggests that steel users will pay an additional $5.6 billion for more expensive domestic steel. In other words, steel users will pay about $650,000 for each job created in the steel industry. Another study calculated employment in the US steel and aluminum industries (mainly steel) might increase by 26,000 jobs over three years, while employment would decline by 433,000 jobs in the rest of the economy, owing to the damage higher steel and aluminum prices have done to downstream industries.”

Great as the costs of Trump’s Chinese trade war were, the economic damage done by protectionist policies did not stop there; a January 2020 report issued by the Congressional Budget Office estimates that,

“[t]ariffs are expected to reduce the level of real GDP by roughly 0.5 percent and raise consumer prices by 0.5 percent in 2020. As a result, tariffs are also projected to reduce average real household income by $1,277 (in 2019 dollars) in 2020.”

Not only have protectionist policies come at a great cost to all involved but it only inspired more retaliation, inching the world closer to the aforementioned mercantilist dystopia that many are still alive to remember.

Free Trade Explained by Production Possibilities Frontiers

The benefits of free international trade, coupled with specialization in those industries in which each country possesses a comparative advantage, goes a long way to explaining the absurdity of barriers to trade. To explain this concept, we will employ a simplified hypothetical example involving two countries, Country A and Country B, and two goods, cars and potatoes.

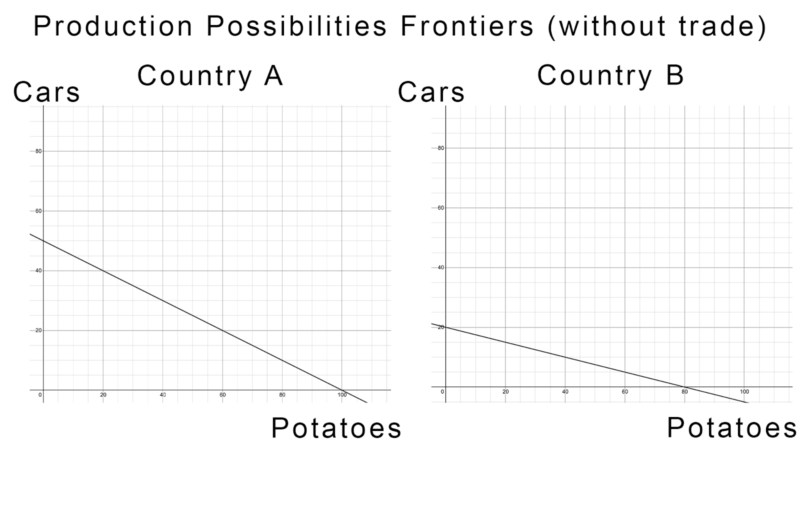

Country A can produce 50 cars or 100 potatoes whereas Country B can produce 20 cars and 80 potatoes; ignoring the law of diminishing marginal returns, we shall proceed assuming a constant linear relationship between these goods for the sake of mathematical simplicity. That said, the domestic trade-off, referred to as a Production Possibilities Frontier, between cars (y) and potatoes (x) in Countries A and B can be modeled by y=-1/2x+50 and y=-1/4x+20, respectively.

Considering Country A can produce more cars and more potatoes than Country B, Country A is said to have an absolute advantage in producing both of these goods relative to Country B. Proponents of isolationism, protectionism, and import substitution argue that a country with an absolute advantage in production needn’t benefit from free trade, because it can produce more of everything than another country. While intuitive, the current example will conclusively demonstrate how this superficial reasoning is incorrect.

Given the unavoidable reality of scarcity of capital, labor, resources, etc. each country cannot produce both their maximum number of cars and potatoes, but must choose to produce maximum quantities of both as defined by their production possibilities curves. That said, there is an opportunity cost associated with producing one good over another for both countries. Although Country A has an absolute advantage in producing both cars and potatoes, it does not have a lower opportunity cost than Country B in producing each of these goods: at any given level of production, Country A can produce 1 car or 2 potatoes and Country B can produce 1 car or 4 potatoes. In other words, Country A has an opportunity cost of 2 potatoes for every car created, whereas Country B has an opportunity cost of 4 potatoes for every car created.

Since Country A can produce a car at the cost of fewer potatoes than Country B, it is said to have a comparative advantage in car production compared to Country B. Conversely, Country B produces one potato at the expense of ¼ of a car whereas Country A produces one potato at the cost of ½ of a car. Therefore, Country B has a comparative advantage in potato production.

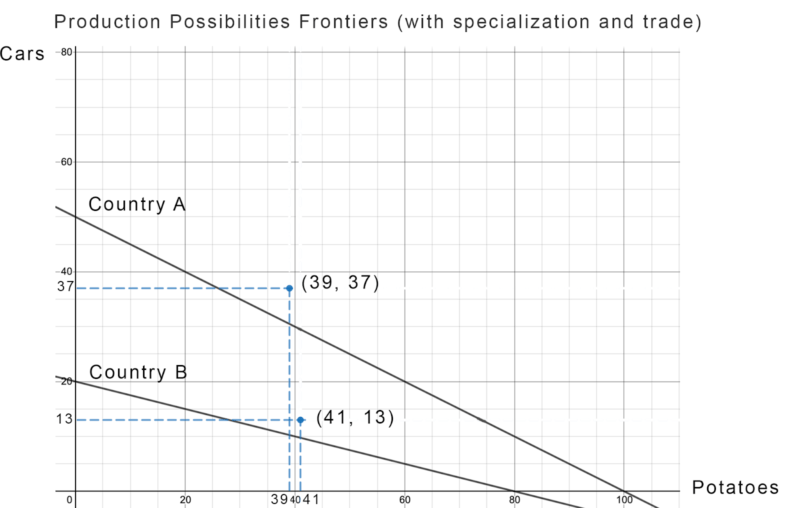

Both countries can enjoy more cars and potatoes than defined by their production possibilities frontiers when each specializes in the industry in which it has a comparative advantage and freely trades at an exchange rate mutually beneficial to both of them, i.e. at a price that is less than their opportunity cost of producing both products domestically. In this example, such an exchange rate would be 3 potatoes to 1 car as this is greater than Country A’s opportunity cost of 2 potatoes to 1 car and less than Country B’s opportunity cost of 1 car to 4 potatoes.

Accordingly, when Country A specializes entirely in cars and Country B specializes exclusively in potatoes, Country A has 50 cars and Country B has 80 potatoes. When they trade at the aforementioned exchange rate of 1 car per 3 potatoes, Country A offering 13 cars for 39 potatoes from Country B, let’s see what the two countries’ consumption looks like relative to their domestic production possibility frontiers:

Almost as if by magic, both countries specializing in what they’re best at and trading freely results in both countries enjoying an aggregate consumption of both goods that was heretofore impossible through domestic production alone. What’s even more amazing is that this is still the case despite one being able to produce more of both goods than the other. The old adage of being your best instead of trying to be the best clearly holds true in the economic realm.

The Economic Philosophy of Free Trade

Despite the compelling theoretical case for free trade, advocates of protectionism sometimes claim that other countries’ cheaper, higher quality goods unfairly outcompete domestic manufacturers. Frederic Bastiat, the 19th century economic journalist and political economist, employs reductio ad absurdum in “The Candlemakers’ Petition” (1845) to reveal the fallacious nature of such a claim:

“We candlemakers are suffering from the unfair competition of a foreign rival. This foreign manufacturer of light has such an advantage over us that he floods our domestic markets with his product. And he offers it at a fantastically low price. The moment this foreigner appears in our country, all our customers desert us and turn to him. As a result, an entire domestic industry is rendered completely stagnant. And even more, since the lighting industry has countless ramifications with other native industries, they, too, are injured. This foreign manufacturer who competes against us without mercy is none other than the sun itself!”

Bastiat goes on immediately to excoriate the policy prescriptions of the allegorical candlemakers and the real-world protectionists:

“Here is our petition: Please pass a law ordering the closing of all windows, skylights, shutters, curtains, and blinds — that is, all openings, holes, and cracks through which the light of the sun is able to enter houses. This free sunlight is hurting the business of us deserving manufacturers of candles. Since we have always served our country well, gratitude demands that our country ought not to abandon us now to this unequal competition.”

The Empirical Record Proving the Theory and Philosophy

Philosophy is key to understanding any concept at its most fundamental level, but what of the real world? Does free trade work out to be as beneficial in actuality as promised theoretically? Does protectionism warrant the derision of economists or are we just a bunch of neurotics?

Fortunately, there is an abundance of modern, real-world evidence to substantiate the more esoteric defenses of free trade and refutations of protectionism. Prof. Doug Irwin of Dartmouth College and his fellow economists at the Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE) quantify the impact of embracing globalization and free trade versus retreating into isolationism and economic populism.

Globalization versus Isolationism

The negative impact of Trump’s recent protectionist policies is not an isolated instance, but representative of a general failure of economic populism that has been documented by economists for decades.

In December of 2020, Prof. Irwin published an article for the PIIE, in which he defends “The Washington Consensus” of free trade and globalization against populist attacks. One of the economic reports Irwin references is that of Kevin and Robin Grier, published in the Journal of Comparative Economics, which found that, between 1970 and 2015, sustained jumps in indexes of economic freedom led to a 16% higher GDP in countries that adopted it after 10 years compared to those that didn’t.

In 2017, economists Zhiyao Lu and Gary Hufbauer of the PIIE updated their

“landmark PIIE study made in 2005, [calculating] the payoff to the United States from trade expansion from 1950 to 2016 at $2.1 trillion. The payoff has stemmed from trade expansion resulting from policy liberalization and improved transportation and communications technology.”

On the other hand, Funke, Schularick and Trebesch conducted a 2020 study that examined the record of 50 populist leaders over the period 1900–2018. These economists found that economic populism, i.e. trade and investment protectionism, expansions in deficit spending, and greater state control of business diminished real GDP per capita by 10 percent after 15 years compared to a non-populist counterfactual.

A similar study on left-populist regimes in Latin America by Absher, Kevin and Robin Grier found that Venezuela, Nicaragua and Bolivia were made 20 percent poorer by such regimes. Despite the egalitarian appeals used by socialists to justify such economic failures, Prof. Irwin notes that,

“[t]hese countries did not experience reduced inequality or improved health outcomes that might have justified such a large sacrifice of income.” (italics my own)

As demonstrated by both theory and empirical evidence, protectionist policies not only make their countries worse off across a variety of metrics but often inspire retaliation that feeds a vicious cycle.

Key Takeaways

Protectionist trade policies have little foundation in sound economic thinking and also bring out the worst in us. It is likely that doctrines such as the Dormant Commerce Clause exist precisely to prevent such experiments within the states, which would not only leave them worse off but create unnecessary tension. It would be wise for our leaders, particularly those in the Biden administration, to heed the clear lessons put forth in our Constitutional system as well as the tides of history. An embrace of free trade will promote widespread prosperity but most importantly, it will prevent a backslide into a past sequence of events that we should be glad to have behind us.