I, Tonya, and the Malleability of Class

The film I, Tonya tells the story of Tonya Harding’s rise and fall as an Olympic ice skater, her stunning talents, her grim private and family life, her wild fame followed by mass public derision, and her final banishment from the sport. Aside from being a fascinating story, it is a rare film for dealing directly with a topic that Americans talk about often but think about hardly any at all: class distinctions and the barriers they create to social and economic mobility.

In the world of ice skating, Tonya was widely seen as tacky, trashy, and a poor example of the ideal type of young woman that the guardians of the sport wanted to put on display. The film treats the problem head on. Tonya believed that judges routinely downgraded her for her demeanor, costumes, choice of music, and lack of the demure elegance they desired in women athletes. Still, she mastered the sport and became the first woman to perform the triple axel in national and international competitions in 1991. No one could deny her credit for that.

She succeeded in sports. She failed to ascend the social ladder. Part of the reason was her own terrible disadvantages. In the film version, the viewer is horrified at the abuse she endures from her mother and boyfriend, and mortified that she keeps getting tripped up by circumstances beyond her control. And yet we are also aware that she bears plenty of personal responsibility for her plight. She seethes with resentment, wallows in victimology, and repeatedly confirms every stereotype. It is a story of fantastic athletic success within a framework of terrible social failure.

Just how malleable is class? What is chosen by the person vs constructed by society? The counterintuitive casting of Margot Robbie as the leading woman flips the observation of Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion. Makeup, accents, demeanor, and temperament can bring anyone up or down the social ladder.

Class as a Concept

And so the movie helps us all confront this strange reality of class that few can define but everyone vaguely knows exists. In American English, we have no “upper class” or even “lower classes”; there is only middle class. We speak of upper and lower middle class. When a politician speaks of coming to the defense of the middle class, that means pretty much every person who can hear.

This interesting use of language is a mighty tribute to the extraordinary power of the American economic engine, that over 250 years it has managed to redefine the entire concept of social stratification. The old world was all about status; the new world provided opportunity for all. We expect people to take advantage of it. When they do not, there is something judgy about the American cultural ethos. We expect all people to rise to the occasion, to behave and think in a way that is up to the standards of their “betters” precisely because we don’t believe that anyone is really better than anyone else.

Thus concept of class still has meaning in American life but defining it is elusive. It’s not really about money, education, privilege of birth, or occupation. To be classy is something within the reach of anyone who wants to master the etiquette manual, dress the part, repair an awkward regional brogue, and otherwise play the part. We speak of people who “marry up” or “date down” so the concept of class is a living reality, even if economic opportunity and our love of merit above station has made it all very blurry.

Tonya’s problem was not so much the perception that she was trashy but rather that she seemed unwilling to upgrade according to the professional expectation. She aspired to be an ice skater. All she had to do, in addition to learning to be the greatest skater in history, was to behave properly, be more sparing in her use of vulgarity, and stop flaunting her low-end class origins. Whenever she tried, however briefly, she failed, and thus came to embrace her difference with others as a badge of honor.

Class and Capitalism

It was Karl Marx who embedded our academic brains with the concept of class as it applies to economics. His notion was not the hazy sense of social status that we commonly think about. He wanted to tie the idea of class to strict categories. There were workers. There was capitalism. They were in conflict, forever facing a terrible reality in which the capital-owners would pillage what should have been justly owned by the workers because it is they who are the value creators. With this model in mind, he made history’s worst prediction: that under capitalism, the workers would grow ever poorer and the capital owners would grow ever richer.

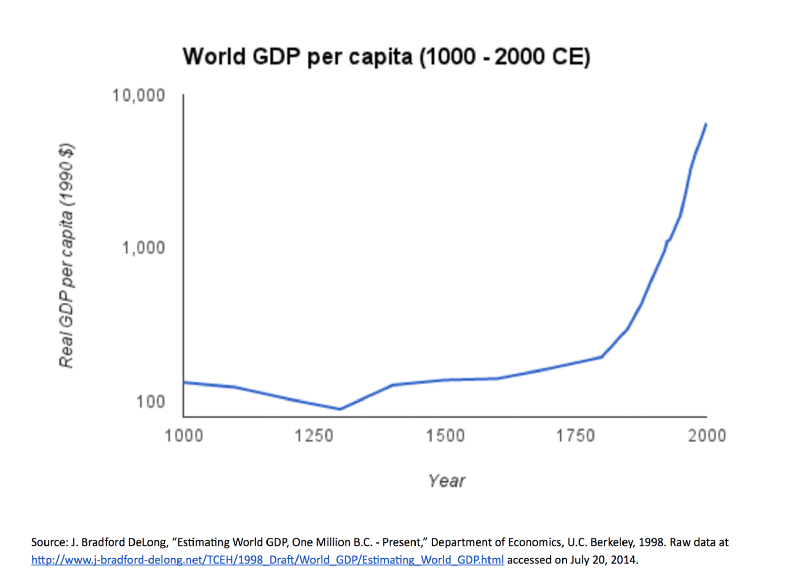

He made the prediction in 1848, just on the cusp of the most gigantic expansion in mass prosperity witnessed until that point in history. Over the following half century, we saw the poor grow rich, lifespans jump, infant mortality plummet, income rise and rise, and the old category of social station grow incredibly malleable. So much for the entrenched Marxian categories; we were moving into a new world of universal opportunity for everyone.

Threatened Position

The great irony of capitalism is not that it entrenched classes; the problem was that it fed resentment among the upper classes (excuse me, “upper middle classes”) that too many people were entering their ranks and threatening their position. The revolt against it took many forms, some of them Marxian. More often, it was the opposite: entrenched elites did not appreciate the uppity ways of the new middle class, the longer lives of the previously poor, the expansion of the population of the previously marginalized.

Having written an entire book on the resentment and revolt of the elites in these years, let me just focus on the strange rise of eugenics in the late 19th century. The literature of the time reflected a sense of panic that just about anyone could mate with anyone else to bear children and thus cause a degeneration in the overall quality of the national stock. This was a large part of the motivation for segregation, marriage licenses, labor restrictions, immigration controls, and compulsory schooling. The drive was not a longing for greater equality but to slow down the mixing of social classes and keeping the rich with a solid monopoly hold on power.

Does that shock you? It shouldn’t. The attempt by the ruling classes to keep their inferiors in their place dates back to the Sumptuary Laws of Colonial New England, as Sarah Laskow explains:

New England’s Puritan colonies had many laws restricting how citizens—particularly women—could dress. “Sumptuary laws” like these weren’t unique to that time or place; they had governed personal behavior as far back as ancient Rome. Usually sumptuary laws were enacted to control behavior in order to distinguish the high classes from the lower ones, though sometimes they were intended to keep wealthy-enough people from squandering all these resources on fashionable indulgences. Pirates’ dramatic and colorful style of dressing was, for instance, a deliberate and brazen violation of these laws…

The Massachusetts Bay Colony passed its first law limiting the excesses of dress in 1634, when it prohibited citizens from wearing “new fashions, or long hair, or anything of the like nature.” That meant no silver or gold hatbands, girdles, or belts, and no cloth woven with gold thread or lace. It was also forbidden to create clothes with more than two slashes in the sleeves (a style meant to reveal one’s rich and fancy undergarments). Anyone who wore such items would have to forfeit them if caught.

We don’t have such laws anymore, but the ambition of the rich to distinguish themselves from everyone else has been the great struggle in the capitalist world in which classes kept getting mixed up. By the twentieth century, this took the form of ever more refinement in tastes of food, manner of behavior, music, and art. And today, you can see this tendency in operation at, for example, the Met Gala where the stars flaunted their edge by dressing Catholic as a way of tweaking the religion of the peasants and working classes.

Refinement in the Class Idea

Under capitalism, it is ever hard to define class by money, occupation, birth, or education, since the freest economies open opportunity to everyone. The impulse to separate “us” from “them” has to take other forms, ever more subtle, ever more refined, ever more easy to bridge. This is surely the most glorious thing about freedom itself, its replacement of an entrenched aristocracy with a new idea of meritocracy. Revealingly, the term only became popular in the late 19th century as it pertained to the civilian bureaucracy: it was not just reserved for the privileged but for everyone based on merit.

The cultural panic about class mixing never ends. We look at popular music, sports, or business and never stop being aghast that this tacky person or that uncouth person could possibly have become rich and famous. We make reality shows about these people, and laugh and laugh at them.

The whole endeavor is harmless, so long as it doesn’t take a political form. What bothers us mostly about the case of Tonya Harding is the perception that her life disadvantages could have found expression in how she was judged in her talent, and also her own indefatigable refusal to step it up a bit to meet with the social and aesthetic demands of the sport. We sense the tragedy. In the end, we as Americans also know the hard truth: she bears most of the blame for her fate.