How America Became Rich, According to a Historian in 1802

For the last quarter century, I have tried to explain the causes of economic growth to my fellow historians. A few have caught on but not the ones whose publications garner the most attention. New Historians of Capitalism/Slavery are the worst offenders, as I showed in The Poverty of Slavery: How Unfree Labor Pollutes the Economy.

To make the matter more amenable to narrative-minded brains, I have long had in contemplation a book that would describe the productivity gains made in a single, typical year. I doubt I will ever have the time or inclination to write an entire book like that, though, because after explaining the role of institutions in creating incentives for people to work harder, smarter, and longer, I soon would grow bored with the details of incremental technological and business process improvements, the nuts and bolts of making more with less.

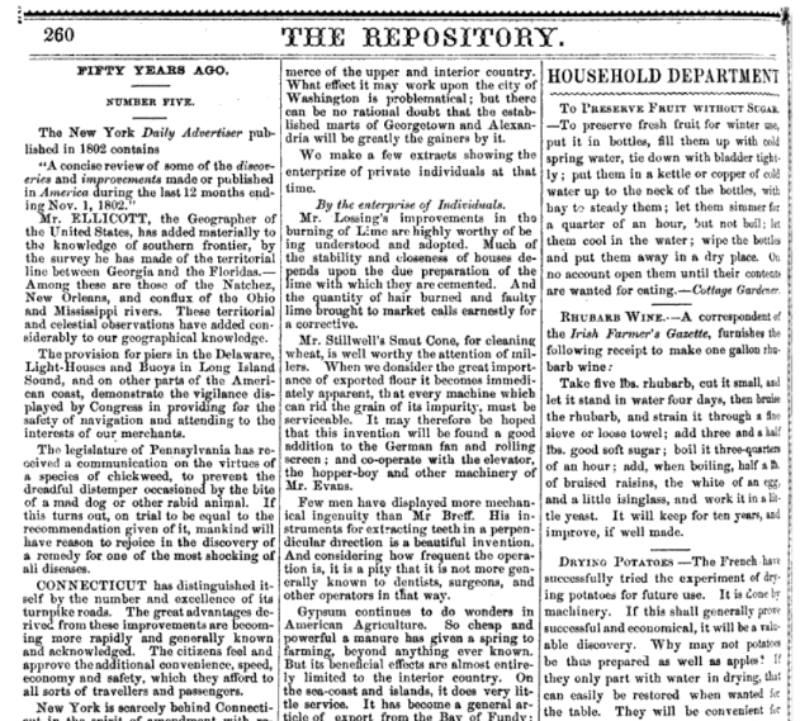

Recently, however, I stumbled upon an article entitled “A Concise Review of Some of the Discoveries and Improvements Made or Published in America During the Last Twelve Months, Ending Nov. 1, 1802” in the 9 November 1802 issue of the Philadelphia North American that captures the essence of the approach I have in mind.

Unfortunately, though, 1802 is a problematic year statistically. According to the best available data, which can be found at Measuringworth.com, per capita income in the United States grew from $80.08 in 1802 to $83.84 in 1803 in current money but, due to a 15 percent deflation in 1802, both figures were down from 1801’s $94.12. In real (2012 USD) terms, per capita income almost did not change between 1801 and 1802 at $1,612 but dropped to $1,589 in 1803. In addition, Joseph H. Davis’s U.S. industrial production index (QJE 119, 4 [2004]: 1,177-215) increased from 7.745 in 1801 to 8.210 in 1802 but slumped back to 7.977 in 1803.

We know the productivity increases described in the 1802 newspaper article reduced such gyrations but they do not present a clean enough growth story for historians, so I certainly would not write a book about 1802.

Nevertheless, the newspaper article is instructive in several ways.

Most interestingly, perhaps, its author credits the U.S. government with several important economic innovations, most of which were clear public goods in the strict sense of the term, including “the provision for piers in the Delaware, lighthouses and buoys in Long Island Sound, and on other parts of the American coast.”

While lighthouses can be, and often were, privately provided, the author was silent about why a sufficient number of lighthouses were not privately provided in early America, but was certain the improvements aided coastal and international commerce.

The author also lauded the government for providing for ailing American seamen in New Orleans, which was not yet a part of the United States and hence not amenable to the formation of non-profit corporations like those that aided sick sailors in New York, Boston, and other American ports.

The U.S. geographer also ascertained the border between Georgia and “the Floridas,” which also seems like a reasonable use of public funds. Moreover, President Thomas Jefferson gained praise for stopping a long-delayed public expedition, approved by John Adams, with the much more dubious purpose of looking for copper deposits south of Lake Superior.

The article’s author also lauded the government for turning over more control to state and municipal governments regarding quarantines. As if channeling Jeffrey Tucker on the coronavirus, he called the federal government’s efforts to stop the spread of infectious disease an “unreasonable absurdity” that caused “alarming loss and damage.”

In short, the author understood that less government generally meant more growth. The major exception was the chartering of non- and for-profit corporations that enhanced productivity by helping people to work harder, smarter, and longer so they could produce the same output from fewer inputs (time, labor, money, material).

The large number and high quality of New York’s and Connecticut’s private turnpike roads garnered much praise for “facilitating intercourse with the remotest part of the commonwealth.” Bridges and short canals around waterfalls also helped to reduce transportation costs. (For all of the business corporations chartered in America, by state, in 1802, browse https://repository.upenn.edu/mead/7/.)

But the most important improvements stemmed from “the enterprize of individuals.”

Mr. Lossing developed a process for burning lime that made the cement used in housing construction more durable.

Mr. Bruff invented an instrument that made it easier to pull teeth, an important improvement given “how frequent that operation” was back then!

Mr. Stillwell’s Smut Cone was not dirty but rather a contraption for removing the impurities from wheat at a great savings of labor.

In Pennsylvania, Col. Alexander Anderson figured out how to distill whiskey faster, while Michael Krufft developed distilling processes that created “a remarkable savings in fuel and labour.”

Gypsum proved such a boon to inland agricultural yields “that all the landings on the Hudson between New-York and Albany” were “loaded and piled with masses of it.”

The introduction of super woolly merino sheep also boded well for increased agricultural output.

Meanwhile, doctors were introducing an improved form of smallpox inoculation and an NGO in New York formed to ensure that poor people would benefit from it too.

Undoubtedly, Americans made many other improvements in 1802 that escaped the author’s notice. But the real story behind America’s 19th-century growth miracle lay not in the details of corporation formation, particular inventions, or the proliferation of innovative practices or better breeds, breads, or meds. With ratification of the Constitution, Americans, white male ones anyway, enjoyed the incentive to work harder, smarter, and longer because they believed their lives and property were their own, to do with as they wanted and not exposed to expropriation by their neighbors, foreign polities, or their own governments.