Can BRICS Displace the Dollar?

BRICS is an acronym for Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa, an intergovernmental organization headquartered in Shanghai. In January 2024, BRICS expanded to include Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates. Argentina was on track to join but withdrew its application. BRICS has evolved as a combination of US allies, non-allied nations, and avowed rivals or outright enemies. The one common denominator is that the BRICS nations are not included in the G7: Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States, with the EU being considered a “non-enumerated member” since France, Germany, and Italy are formal members.

BRICS announced the formation of the New Development Bank (NDB) in 2012 to augment lending to member nations. BRICS’ perspective was that the World Bank, the IMF, and various other development lenders had failed to lend enough and focused available lending on priorities chosen by the US and other Western countries. The NDB began lending in 2016, particularly emphasizing green and environmentally friendly projects. The BRICS’ 2015 summit announced they would explore creating a new reserve currency that they would use in preference to the dollar.

What is a reserve currency, and how did the dollar come to be one? Under the gold standard, virtually all payments for international trade were made in gold coin, making a reserve currency irrelevant. Nations often suspended the gold standard during times of conflict. The US, for example, went off in 1861 and was unable to resume until 1879. Most international payments still had to be made either in gold or equivalently in some gold-backed currency. During the First World War, virtually all belligerents went off the gold standard, but the US was an exception since it did not join the war until April 1917. By 1920 the dollar was replacing the British pound as a reserve currency. The dollar remained the reserve currency of choice through the Great Depression, even though it was devalued significantly in 1934 because all potential alternatives were performing even worse.

At the end of the Second World War, the 1944 Bretton Woods Conference envisioned the US remaining on a tenuous gold standard — the dollar had been legally defined as 1/35th of a gold ounce since 1935, even though since 1932 the dollar had not been convertible to gold. Under the Bretton Woods system, other countries would define their currency in terms of the dollar, which would put them on a technical and legal gold standard, but without any expectation of convertibility. Other countries could and did devalue at will, changing their dollar exchange rate. Devaluing made their exports cheaper for Americans to buy while protecting domestic industries from US imports that devaluation made more expensive.

After about twenty years under the Bretton Woods system, the dollar faced the fiscal pressure of government budget deficits from President Johnson’s Great Society programs and the Vietnam War. The last link to gold was lost in 1973 when President Nixon had the Treasury stop selling gold to foreign governments for $35 per troy ounce. The dollar persisted as a reserve currency largely because it generally depreciated more slowly than alternatives. The best candidates for alternative low-inflation, sound-money reserve currencies were the Deutsche Mark, the Japanese Yen, and the Swiss Franc. The Mark and its successor the Euro, have had some traction as an alternative to the dollar. The Yen outperformed the dollar in terms of retaining value until about 1990 when the Bank of Japan started to listen to American academic economists who counseled more inflationary policies. The Swiss Franc continues to be a better store of value than the dollar, but never became a reserve currency because it is not as widely used in world trade.

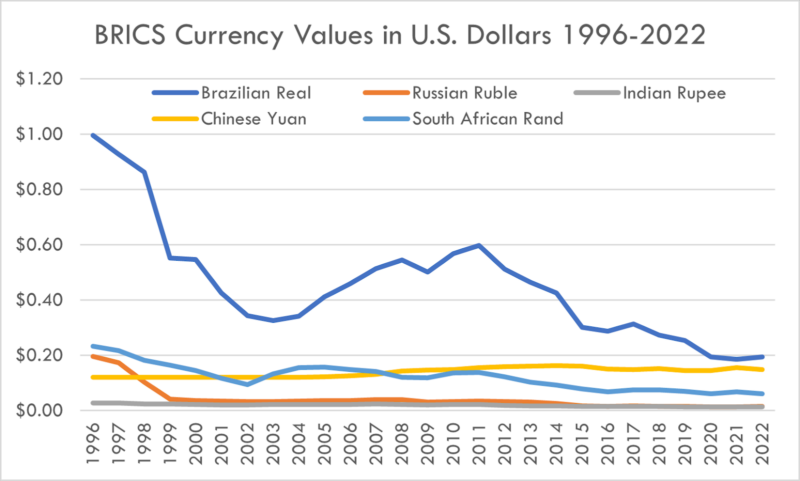

BRICS would have a strong case for replacing the dollar with a reserve currency of their own, except that the performance of their currencies has generally been even worse than the dollar as shown in Figure 1.

(Exchange rates from the World Bank)

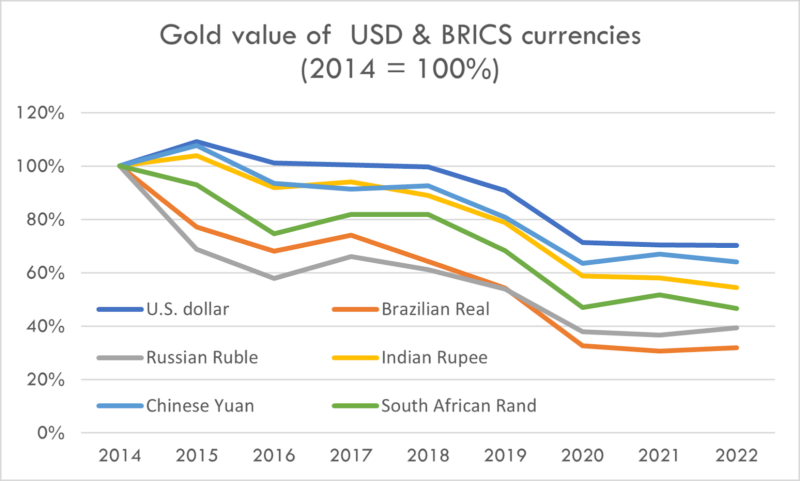

The ruble, rand, and real have all depreciated quite significantly against the dollar since 1996, but keep in mind that the dollar itself has depreciated markedly over the same period. This can be seen by comparing each currency’s performance against gold since the end of the Great Recession in 2014. Taking the 2014 gold value of each currency as 100 percent, all have performed significantly worse than the dollar as shown in Figure 2. The dollar has been no great shakes but it beats the BRICS currencies.

The noise from BRICS about creating their own reserve currency and abandoning the dollar is little more than noise. As irresponsible as the Fed has been, BRICS policymakers apparently want to inflate faster than even the Fed will allow. They do so at their own risk. At least some BRICS nations could potentially outpace the G7 in growth and performance, but not by adopting monetary policies that are even more value-destroying than those of the European Central Bank and the Fed.