Best of 2015: Medicare is Hardly Self-Financed

This week, as we recharge for the new year, we highlight a few of our best-read blogs of 2015. This piece originally ran in August.

Many believe that Medicare (similarly to Social Security) does not add anything to the federal budget deficit because it is financed by dedicated tax revenue. This belief is one of the reasons for the outrage at the suggestion that Medicare needs to be reformed to prevent future budget deficits from spiraling out of control.

But this belief is at odds with reality. Every year, Medicare eats hundreds of billions of dollars out of the federal budget over and above the Medicare taxes that we all pay out of our paychecks.

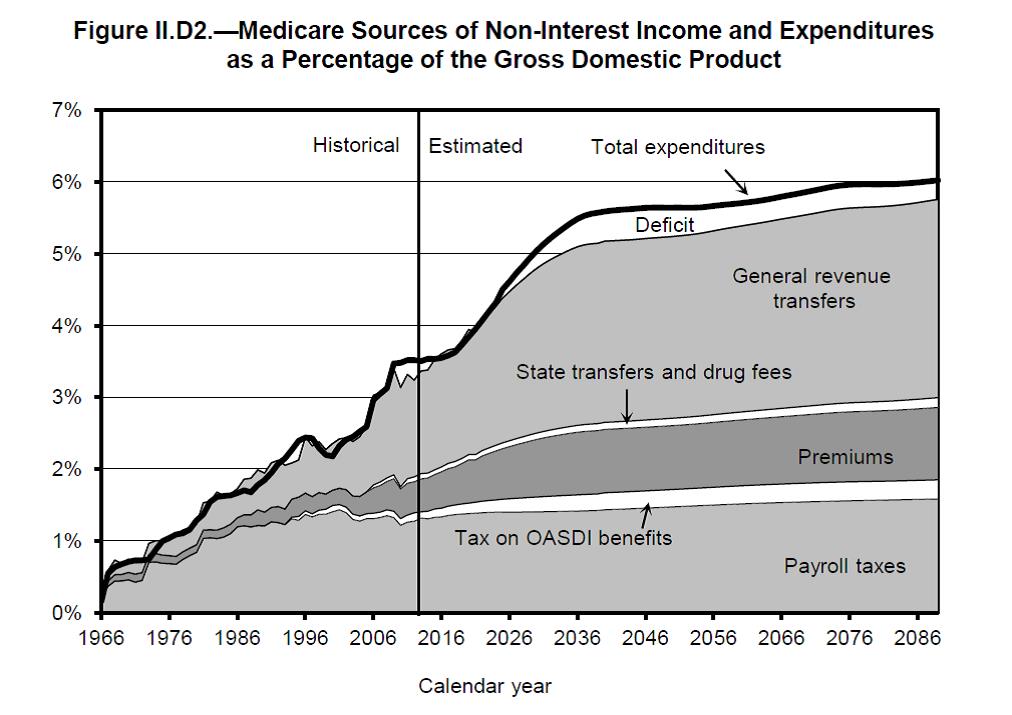

Here is a chart, taken from the 2015 Annual Report of Medicare Trustees, that shows all sources of Medicare funding.

The bottom area is payroll taxes – these are the Medicare taxes deducted from our paycheck and those paid on our behalf by employers. Tax on OASDI benefits — that stands for Social Security’s official name, “Old Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance” — are the taxes that some Social Security recipients pay on their Social Security benefits because they have other income that exceeds a certain threshold. Those taxes are earmarked for funding Medicare.

The darker grey area called Premiums represents the premiums that are paid by those who signed up for Medicare Part B (which pays for physicians’ services) or Medicare Part D (which pays for prescription drugs). Medicare Parts B and D together are also called Supplemental Medical Insurance. The part of Medicare that pays for hospital stays (called Medicare Part A, or Hospital Insurance) does not have any premiums. This is the part of Medicare that is mostly financed by the payroll taxes we all pay.

Medicare Parts B and D are not funded by the payroll taxes. Instead, the premiums that enrollees in these programs pay are calculated every year so that they cover about a quarter of the total cost of these programs. The other three quarters of the cost are covered by general tax revenues. That’s what the General Revenue Transfers on the chart above represent.

Note that so far (in the historical part of the chart), the general revenue transfers were comparable in size to the payroll taxes. In the future, however, they are expected to be much higher than payroll taxes. This is because, in making projections for the future, Medicare trustees make an assumption that the laws will stay unchanged from what they are today. And the law today specifies what the Medicare payroll taxes are: 1.45 percent paid by the employer and employee each, with some additional taxes on people with income above a certain threshold.

But the law today does not set any limit on what the general revenue transfers for financing Medicare Parts B and D can be. Under the current law, the general revenue transfers will be three quarters of the cost of those programs, no matter how high those costs happen to be.

In 2014, the federal budget transferred around $247 billion from the general tax revenue to fund Medicare Parts B and D. That is a little more than all of the Medicare payroll taxes collected last year ($227 billion), which were used to fund Medicare Part A. It is also about 40 percent of all Medicare expenditures in 2014. For comparison, this is around 42 percent of the entire military budget for 2014.

This is not a trivial amount of money in relation to the overall federal budget. The general revenue transfers that went to fund Medicare Parts B and D, at $247 billion, or 1.4 percent of GDP, were about 7.9 percent of all federal revenues collected in 2014, and about 6.9 percent of all federal outlays that year. They are equal to around a half of the federal budget deficit in 2014.

In other words, Medicare, in addition to consuming all of the Medicare payroll taxes we pay each year, also consumes about one out of every 12 dollars we pay in all other federal taxes. Self-financed it is not.