A Bill to Ease California’s Housing Shortage

For years now California families have suffered from high housing costs. Rent burdens grow nearly every year in one of the most livable and highly productive places on the planet, a phenomenon that scholars argue drags down the national growth rate.

A new bill before the California legislature could help end the state’s chronic failure to allow enough homebuilding to meet the demands of its citizens. The bill would ease a variety of restrictions on properties near transit stations and bus stops with frequent service. In many places, this would amount to a dramatic up-zoning, enough to trigger the massive increase in the size of the housing stock needed to bring rents back toward those in peer cities.

Gone would be the days of single family homes across the street from a subway station. On wider streets, buildings could be 85 feet, or about eight stories, tall. Narrow side streets would allow buildings up of four or five stories. Municipalities could not mandate parking or the floor-area ratio of these properties, further limiting their ability to block density.

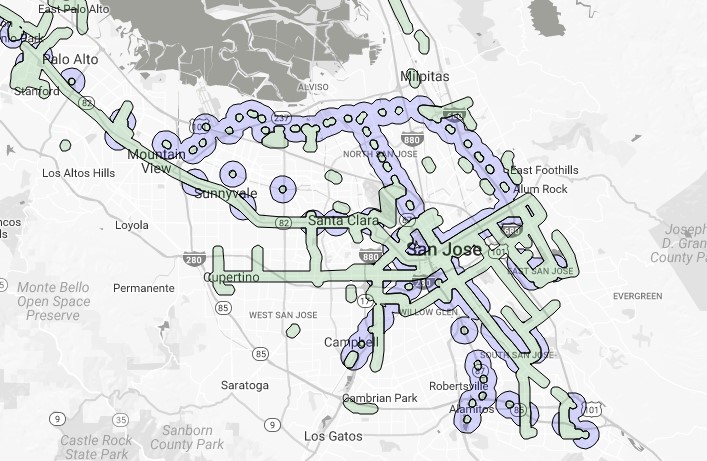

To put this in perspective, below is a picture of the San José area, and the shaded areas below (both colors) would be subject to these new rules. Many of the city’s existing high-density areas fall in the up-zoned area, but also many lower-density parts of the city, such as the area between Alum Rock and Milpitas to the east. You can see a map estimation for other communities here.

Building more housing is controversial. It has transitional costs that matter to people. Construction is annoying. The prospect of less parking and more competition for tables at local restaurants is dreadful to many. This says nothing of potential noise and traffic complaints.

This bill would help overcome local opposition to some of the state’s most famed bastions of NIMBY activism, like Berkeley and San Francisco. Berkeley’s mayor so much as called the bill “A declaration of war against our neighborhoods.”

But this is the cost of delaying much-needed housing for years. To bring the state’s rents down, hundreds of thousands of homes need to be built. Until then, high rents will generate political pressure for liberalization of building rules. Other high-rent states, notably Massachusetts, have their own reform efforts on the table.

Under SB 827, municipalities then face a choice: either they allow enough building somewhere in the area, perhaps a cluster of towers in a hilly part of town, or accept extra density near existing transit stations. To preserve the character of one place, they must accept building in another.

This is how a healthy housing market works. If California passes SB 827 or some similar reform in future years, much of the problem of a general lack of places to build homes would be largely alleviated. With vast swaths of newly up-zoned area, two-story bungalows would slowly give way to seven-story apartment blocks and condo buildings, housing many more people. More people near transit could also increase ridership and decrease the need for subsidies, if capacity is as plentiful as in cities like Los Angeles.

Citizens care about rents, and legislators will continue to bring bills to alleviate them until the pressure is gone. Until then, we can expect more bills like SB 827.