Tariffs Successfully Raised the Trade Deficit

One of the reasons the United States is now waging a trade war with China and other countries is that the president hates trade deficits. He apparently believes that if other countries lowered all of their tariffs and thus bought more American exports, we would run trade surpluses. To force their hands, the president is raising tariffs — that is, taxes on American purchases of foreign-made goods — hoping that Beijing and other foreign governments will cut their own tariffs and thus help to lower the U.S. trade deficit.

But the president is completely mistaken. By his own standard of success, his trade war has failed. American tariffs are up and imports are down, and yet the U.S. trade deficit is up. (For argument’s sake, I here accept President Trump’s false belief that bilateral trade deficits and surpluses are economically meaningful.)

According to the Census Bureau, as of October 2018 our trade deficit in goods with the world stood at $76.98 billion, up from $68.5 billion in March 2018, when the tariffs on metal were first announced, and up from $72.0 billion in July, when they were first imposed. At this rate, the total trade deficit in goods with the world in 2018 will be significantly higher than it was in 2017.

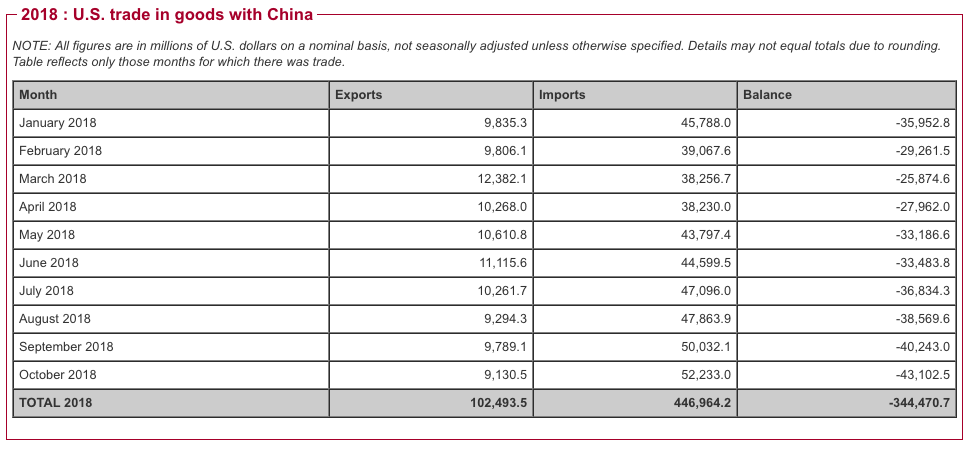

The story is pretty much the same with China. We started 2018 with a trade deficit in goods with China of $35.9 billion, and after months of tariffs on Chinese imports in the United States, as of this past October this deficit with China stands at $43.1 billion. If I were a betting woman, I would wager that America’s trade deficit with China in 2018 will easily surpass that of 2017.

I guess tariffs aren’t all that Tariff Man believes them to be.

Now, to be fair to the president, if you impose higher taxes on goods and services that Americans buy from abroad, consumers will over time shift their demands to any now-relatively-cheaper American goods. We see this substitution as a result of tariffs on Chinese goods. While imports of Chinese goods have continued to grow, the rate of growth has dropped. But we see something else in addition: since May 2018, U.S. exports to China have dropped in absolute terms.

For one thing, contrary to the administration’s promise, unilaterally raising tariffs hasn’t resulted in reduced foreign tariffs and better access to foreign markets for U.S. exporters. Instead, foreign tariffs have gone up, and threats of retaliation continue. That explains some of the drop in exports to China. But that’s not all that is at play here.

First, the president is wrong to believe that the trade deficit is a sign that everyone is taking advantage of us. It is actually quite the opposite. Persistent and rising U.S. trade deficits signal that the United States is an attractive destination for foreign investors looking to make a profit. I suspect that Trump’s tax cuts and deregulatory efforts have contributed to making the U.S. market even more appealing. These positive policy developments likely shifted foreign-owned dollars away from buying U.S. exports (especially because their prices are driven higher by retaliatory tariffs and a stronger dollar) and toward investments in the United States. Meanwhile, richer Americans can afford to buy more imports, even if they are becoming more expensive. With genuine economic growth, there often comes a larger trade deficit.

Unfortunately, at some point this silly worry about trade deficits will take a real toll. Overall American imports might actually start going down. While Mr. Trump may see this fall in imports as a good thing, it really won’t be. Here’s the thing that most people, especially the president, fail to understand: if imports fall, so will exports. This counterintuitive reality is easily understood if one thinks of how foreigners acquire the dollars they need to buy U.S. goods.

The single biggest way to acquire dollars is to sell goods and services to Americans — goods and services that Americans import. We get valuable outputs from foreigners in exchange for little green bills. The fewer are the dollars that foreigners earn by selling their exports to us, the fewer are the dollars available to them to buy our exports.

As Adam Ozimek, an economist at Moody’s, aptly put it, “The Trump administration is learning you can’t tariff your way out of a trade deficit.” By the way, nor should anyone want to do so, because U.S. trade deficits are typically desirable rather than undesirable.