Paper Money in Colonial North Carolina

American history provides many examples of how monetary systems can be run. The colonies and states were isolated monetary experiments without any central coordination. Some systems led to sound money, and others became utter failures. As Paul Samuelson said, “American history is peculiarly well-suited to throw light on the nature and development of money.”

However, one major problem surrounds studying money, especially during the colonial period: the data haven’t survived, if they ever existed. Treasury records were lost to trash bins. Legislative records were lost to fires. Simple administrative questions like “How much money did the North Carolina government issue?” often cannot be answered.

When direct records do not exist, researchers must rely on fragmented information and reconstruct the numbers from a variety of sources. A recent NBER working paper by Cory Cutsail and Farley Grubb reconstructs such numbers for North Carolina’s paper-money regime from the time of its first paper money, emitted from 1712 to 1774.

Cutsail and Grubb compiled a yearly record of newly printed bills, the value of those bills relative to the British pound sterling, the total bills in circulation, and more. By using a combination of tax records, personal letters, and government letters, Cutsail and Grubb put together the most complete data set so far assembled. While the main contribution of Cutsail and Grubb’s paper is to reconstruct the monetary data, which is interesting in its own right, the paper also explains the structure of the paper-money regime in North Carolina.

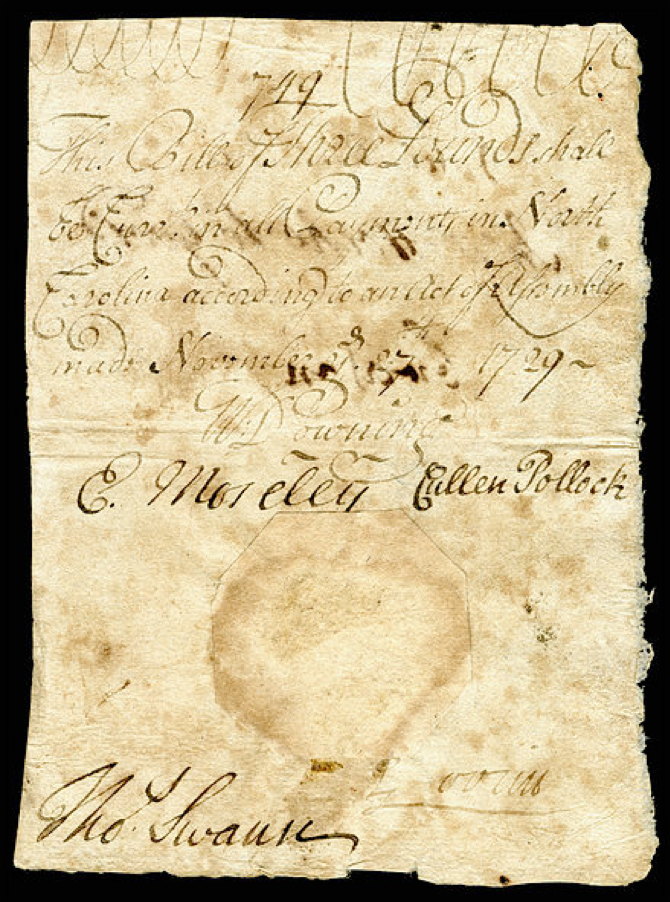

Reconstructing this history requires an understanding of the North Carolinian economy as a whole. Today we talk about paper money and contrast that with commodity money like gold or silver. During the colonial period, paper money meant bills of credit, which were printed by each state’s legislature. In North Carolina, the state assembly would directly print bills through a press or handwrite them, as shown in the picture below. The assembly would then place the new bills in the treasury so that they could be directly spent on soldiers’ pay, military provisions, salaries, and so on.

The assembly issued these bills of credit to finance wars, as was common for governments throughout history. For North Carolina, the first bills of credit were issued to finance the first war after splitting from South Carolina, the Tuscarora Indian War (1711–15). Bills of credit continued to be issued for other wars up to the American Revolution, such as King George’s War (1744–48) and the French and Indian War (1754–63).

While the colonial governments had a revealed desire to fight wars, the assemblies did not have the capacity to finance wars by collecting taxes directly. In addition, the state governments could not mint coins directly to finance the war, as was common for wars throughout Europe. The Crown reserved that right for itself.

States like North Carolina stumbled on a solution by spending bills into circulation for the immediate war expenses. Future taxes would then be payable in the bills. This would remove them from circulation.

Although they were simply trying to finance wars, the legislatures in colonial America indirectly created media of exchange by introducing the only circulating paper monies at the time. In contrast to later periods, banks did not issue paper banknotes in colonial America. It was not until the end of the American Revolution that banks successfully emitted paper notes redeemable in specie on demand. The bills of credit completely changed how the economy and government of North Carolina operated.

As Cutsail and Grubb point out, before the paper money issued by the assembly, “North Carolinians primarily used direct barter of agricultural commodities.” In the 18th century, on the eve of Britain’s industrial revolution, people in colonies of the world’s most advanced economy were primarily trading pigs directly for cotton (for example). This was no modern industrial economy.

The barter nature of the North Carolinian economy further highlights why military financing was so difficult and why bills of credit were so important. It wasn’t just that the assembly did not have the capacity to go around and collect coins. The government would have had to collect taxes in the form of agricultural commodities: two pigs from Johnson, one bushel of cotton from Smith, and so on. A real medium of exchange revolutionized the economies of the colonies.

Returning to the paper, Cutsail and Grubb use knowledge of North Carolina’s economy and fiscal system to learn about its monetary system. For example, the authors use a letter that Colonel Alexander Spotswood wrote to the Board of Trade on May 8, 1712, stating that North Carolina had raised 4,000 North Carolina pounds. The authors can infer that this tax revenue was raised by issuing bills of credit.

Even though the direct documents related to the issuing of the bills of credit have been destroyed, the indirect records about tax collection suffice to fill in some gaps. Cutsail and Grubb have provided researchers with valuable data to better study the economic, political, and social history of 18th-century North Carolina, a transitional time and place in American history.