How Can Governments Borrow at Such Low Rates?

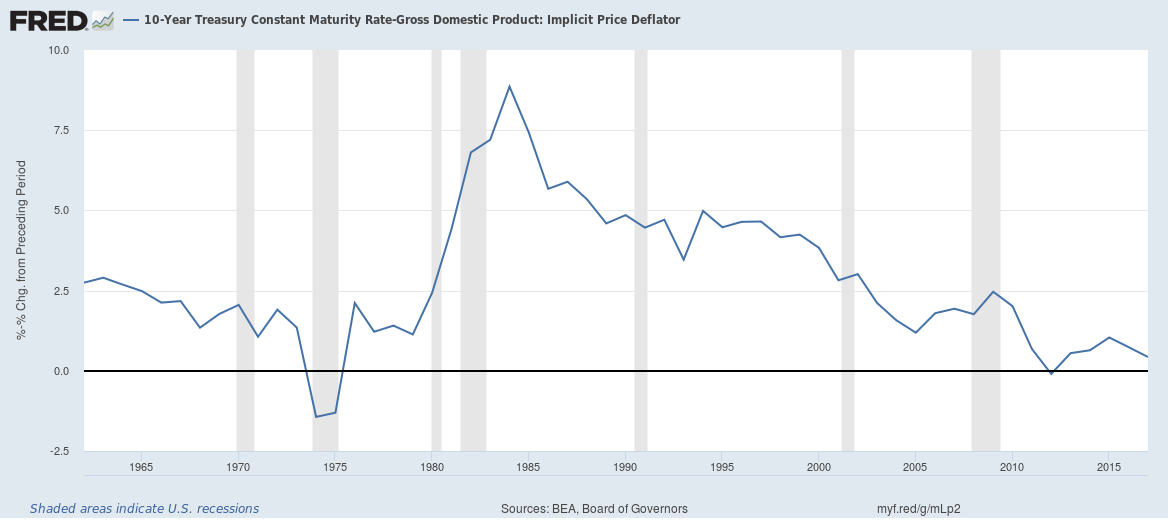

In his recent presidential address to the American Economic Association, Olivier Blanchard notes the decline in interest rates on government bonds since the 1980s. In Q3 1984, for example, the real interest rate on 10-year U.S. Treasuries was around 9.33 percent. By Q3 2004, it had fallen to roughly 1.50 percent. More recently, in Q3 2018, it was a mere 0.53 percent.

With this in mind, Blanchard considers the implications for government debt policy and reaches what he describes as a surprising conclusion. “Put (too) simply,” Blanchard notes, “the signal sent by low rates is that not only debt may not have a substantial fiscal cost, but also that it may have limited welfare costs.”

If Blanchard is correct, there is little reason to be concerned about the $21,195,070,000,000 in debt carried by the federal government, which amounts to roughly $64,628 for every man, woman, and child currently living in the U.S. Indeed, if the costs are so low, it might even make sense to finance additional government expenditures by running an even larger deficit each year. Paul Krugman, discussing Blanchard’s work in the New York Times, expresses this view clearly: “it’s becoming increasingly doubtful whether there’s any right time for fiscal austerity. The obsession with debt is looking foolish even at full employment.”

Let me be clear: I believe Blanchard’s work is theoretically sound and I am not especially concerned with the current level of the national debt in the US. I do not believe the current level of debt is a significant drag on the economy. And, whereas others express concern about another epic economic collapse, an inevitable debt collapse, or the so-called fiscal time bomb, I have little doubt that the government will be able to service its debt into the foreseeable future.

I believe the debt is too large, to be sure. Politicians are short-sighted. They are prone to overspend and undertax in an effort to court current voters, who enjoy the benefits of expenditures funded, in part, by future taxpayers. That is a problem. I just don’t think it is a very big problem. We should take modest steps to reduce the deficit, preferably by eliminating wasteful spending and closing costly loopholes in the tax code. We should consider fiscal rules to keep deficits under control in the future. But we need not panic.

In other words, my disagreement with Blanchard is subtle. In brief, I do not believe the interest rates on government bonds reflect the opportunity cost of borrowing.

To get a better sense of the issue, let’s first consider the interest rate that emerges in a purely private lending scenario. Suppose, for example, that a private borrower plans to open up a coffee shop. Her business plan is pretty simple: she will acquire an expensive espresso machine and some modern furniture, hire a few congenial baristas, and convince others to hand over their hard-earned cash for her high-end lattes. Her ability to repay the loan depends entirely on the productivity of her project. After evaluating the project, private lenders will compete to extend the loan. The result is an interest rate that reflects the market’s best guess of the project’s risk-adjusted rate of return.

Suppose, instead, that an equally capable government were to pursue the very same business plan. Unlike the private borrower, who must rely exclusively on willing customers, the government has an additional source of funds: taxpayers. In other words, the government can convince others to hand over their hard-earned cash for its high-end lattes. But it can also compel its citizens to pony up should the coffee venture fail to raise sufficient funds to repay the loan. Hence, when evaluating the government project, lenders will not only account for the risk-adjusted rate of return of running a coffee shop but also the implicit insurance policy provided by the taxpayer backstop. Since, all else equal, an insured project is less risky than an uninsured project, the government will typically be able to borrow at a lower rate.

Isn’t this great for society? Under both scenarios, we fund a coffee shop. (And it is hard to beat a delicious latte in the morning.) But, if the government takes on the project, we fund it at a lower interest rate. That seems like a pretty good deal.

Not so fast! The interest rate our private borrower pays reflects the opportunity cost of the loan to society — that is, the value of the most desirable project forgone in order to make the loan. But the rate the government pays merely reflects the price of the loan to the government. The cost of the loan to society is equal to the price of the loan paid by the government plus the cost of the implicit insurance policy provided by the taxpayer. By assumption, the private and public borrowers in these scenarios are taking on the very same project.

By assumption, the government is no better nor worse at running a coffee shop than the private borrower. Hence, the opportunity cost to society is the same in both scenarios despite the lower interest rate available to the government.

Where does this leave us? Quite naturally, governments should take on projects when (1) the benefits exceed the costs to society and (2) the government is the lowest-cost provider of the good or service in question. Unfortunately, the interest rate on government bonds is a poor indicator of when those two conditions are met. A government can take on a net-cost project and repay the loan with taxpayer funds. It can take on a net-benefit project at a lower rate but higher cost than private sector competitors.

Those who cite low interest rates on government debt miss the point. It is not the price of government borrowing that matters. Rather, it is the opportunity cost of government borrowing to society.