Here’s Why We Tolerate Fake Check Scams

The daily news is filled with personal stories about bad experiences with banks. Here’s a recent example. A Toronto man was tricked by a job scammer into accepting a fake check. The man’s bank let him cash the check, only to discover it a few days later. The bank then raided the man’s savings account for the full amount.

Readers will find this story disturbing. Banks are supposed to protect scammed customers, not kick them while they are down. Many of us will wonder if the payments system needs to be fixed.

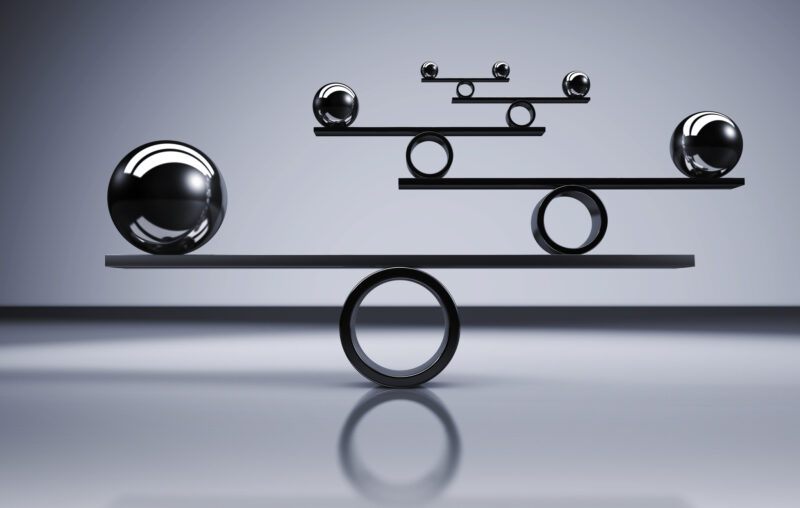

But payments systems are complex organisms that have evolved over many centuries. When viewed from afar, what appears to be a glitch is often actually an element of a balanced whole. Solving the problem of fake check scams would upset this balance, introducing new complications further down the payments process.

Let’s look a bit more closely at the scam.

The anatomy of a job scam

Promised a job at home by his new employer, Justin Smith was sent a $3,495 paper check to buy office equipment. Smith proceeded to deposit the check at his bank, which immediately credited him for the full amount. He then transferred $3,000 electronically to pay for the equipment. This was certainly an odd request for an employer to make, but we can forgive Smith, who like many job seekers was eager to start working.

But it was a scam. The check, job offer, and equipment seller were all fake. Unfortunately, the $3,000 that flowed out of Smith’s account and into the account of the scammer’s nonexistent equipment seller was very real. Smith’s bank promptly seized $3,000 from Smith’s savings account as compensation for the amount of money that it had created for Smith upon accepting the fake check.

Unjust? It seems so. Desperate job seeker gets tricked by scammers only to have his fat cat banker, the one who processed the check, refuse to help him. Unfortunately, scams like this are all too common.

Exploiting the check timing gap

In addition to exploiting the desperation of unemployed workers, job scammers exploit a weakness in the check payments system. Specifically, they target the timing gap between a bank’s initial crediting of funds to a depositor’s account and the point at which a check’s authenticity is finally verified.

When someone accidentally brings a scammer’s fake check to the bank, banks will do their best to catch it. But some fakes sneak through. This is where the timing gap opens up.

The amount indicated on the face of the fake check is credited to the depositor’s bank account. The customer can then spend it (or be duped into paying off their scammer). But behind the scenes the actual processing of the fake check grinds on. A few days or even weeks later the check’s true nature is eventually discovered. But, by then, the sneaky scammer has already received their electronic payment.

So why don’t we just fix things by removing the timing gap?

The tradeoff between speed and security

The payment system is a combination of tradeoffs and sacrifices. We can remove the check timing gap, but this means introducing other weak spots into the checking system.

For instance, we could easily put a quick end to all job check scams by stipulating that banks only credit funds to depositors’ accounts after the check has been irrevocably confirmed to be legitimate. In that case, if Justin Smith were to accidentally deposit a fake check, he needn’t worry. The check will eventually be caught and he won’t be hit with a $3,000 charge. Knowing that the system has a perfect defence, scammers would stop check scamming.

But there are consequences to fixing the timing gap. All of us check-users would now be required to wait days, even weeks in some cases, before we can spend our money.

Speed is an important feature of any payments system. Because Justin Smith was a longtime customer of his bank, it allowed him to withdraw the amount printed on the face of the check immediately, even though the check hadn’t definitively settled. In bank-speak, banks will lend or grant provisional credit to their check-cashing customers.

This service is important to us. We may have bills due two days from now. We can’t wait weeks for our checks to be 100% settled.

In fact, check speed is considered so important that according to U.S. law, all checks deposited must be made available for withdrawal by the business day after the day of deposit. Since the only way for banks to meet these standards is to grant provisional credit, the timing gap is legally baked into the system.

And into this gap scammers stream. We accept these chinks in the check system because we want the overall process to move more quickly.

Who bears the costs of speedy checks?

If society has decided to tolerate the fake check problem in order to get more speed out of the check system, someone has to bear the extra credit risk of these fakes. Which unfortunate party is held responsible?

Commercial law places this risk squarely in the lap of bank customers. When a bank puts money in a customer’s account upon deposit of a check, it is lending to them. As with any loan, the lender can collect should the borrower default (say, because the check was fake).

That’s exactly what happened with Justin Smith. He was granted provisional credit after depositing a fake check, only to get dinged with a charge when the fake was discovered.

We might not think this is fair. Surely banks are better at evaluating whether a check is fake or not than customers. So why not shift the burden of absorbing the cost of fake checks onto banks and away from the public?

We could certainly design a payments system along these principles. Now when Smith deposits a fake $3,000 check, and his bank credits him the amount, Smith’s bank must absorb the $3,000 expense when the fake is discovered.

In this system, not only would banks make check payments go fast by offering provisional credit. They would also take on all of the risk of fake checks. What a win for bank customers! We’d get maximum speed and complete safety.

But it’s not that easy.

To absorb the costs of extra credit risk, banks would probably increase monthly checking account fees. Rather than passing on the costs of fake checks exclusively to the scammed customers, as in the current system, every customer would bear part of the burden in the form of higher fees.

This spreading-out of costs is a win for vulnerable customers who, given the precariousness of unemployment, are more likely to fall for job scams and be hurt by associated penalties. But the rest of the bank’s customers may not be as thrilled, preferring charges fall on those who make mistakes.

In sum, what happened to Justin Smith is unfortunate. But solving the problem of job scam checks isn’t as easy as one might think. Changes to a tightly-wound system like the check system involve tradeoffs. You don’t get something for nothing.