Cash Is King in COVID-19

Worries about the coronavirus and the government’s response are having dramatic impacts on our financial decisions. One of the instruments that people are turning to is the good ol’ fashioned banknote.

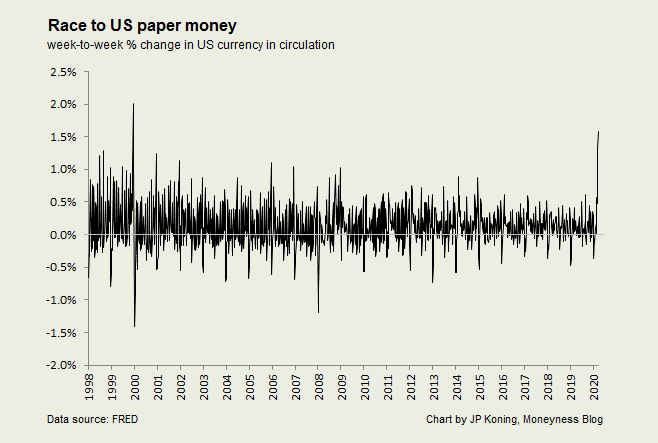

Over the last two weeks, the supply of Federal Reserve banknotes has increased by around $70 billion to $1.876 trillion, a week-to-week increase of 1.75%. As the chart below illustrates, this is the fastest weekly increase in cash in circulation since December 1999.

What happened in 1999? In the weeks leading up to the 2000 century date change, people flocked to U.S. banknotes because they were worried that computer glitches would bring down the financial system.

Holding more cash during difficult times is not unusual. Banknotes and deposits are the best instruments for dealing with the discomforts of uncertainty. Because these instruments are liquid and stable, anyone who owns them is assured that should some unanticipated need arise, they can quickly mobilize their resources to cope.

Hoarding money is often vilified as idleness. But the economist William Hutt, who wrote one of my favorite essays on money, disagreed. When we hoard money, we aren’t just sitting on an idle resource, wrote Hutt. This money is doing hard work, the essence of what he referred to as “availability.” When money is sitting in our pockets or our tills, it’s like a “piano when it is not being played, or a fireman or a fire engine when there are no fires.”

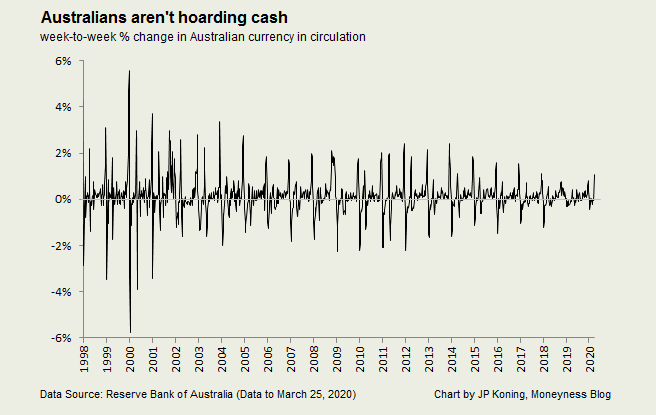

While there has been a big rush to US banknotes, the same isn’t happening in other countries. Below is a chart showing the week-to-week increase in Australian banknotes outstanding.

While Australians are certainly holding more cash than before the pandemic, this month’s dash into paper money is no bigger than the seasonal Christmas switch into banknotes. At the end of each December, Australians typically push the domestic currency supply up by around 1-2%, perhaps because they are giving cash as a gift or withdrawing some extra notes for travel purposes. (Since the U.S. and Australia are some of the only nations that provide weekly banknote data with little to no lag, it’s hard to get a feel for how other nations are acting.)

We need to be careful about comparing the U.S. to Australia. Since the Australian dollar isn’t used internationally, we can be quite confident that the entire rise in Australian currency in circulation can be explained by the behaviour of Australian citizens. But U.S. banknotes are popular all over the world. So we don’t really know how much of the huge jump in banknote demand can be attributed to Americans, Russians, Veneuzelans, or others.

Banknotes and deposits are great hedges in uncertain times, but they aren’t perfect substitutes. If the supply of cash is rising as people line up at ATMs, this comes at the expense of deposits.

This month’s rush into U.S. cash doesn’t constitute a bank run, however. The total stock of U.S. dollar banknotes jumped by $70 billion in March. That sounds big (and it is big relative to previous jumps in cash outstanding), but it’s peanuts compared to the $15 trillion or so in checking and savings deposits in existence, not to mention trillions more overseas.

Some people are counselling Americans against rebalancing from deposits to notes. In a recent video, the head of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) Jelena McWilliams had this to say: “Your money is safe at the banks. The last thing you should be doing is pulling your money out of the banks now thinking that it’s going to be safer someplace else.”

McWilliams is right. A hundred bucks in an FDIC-insured bank account is just as financially sound as a $100 banknote, with none of the risks of burglary.

But at the same time, there are good reasons for taking at least some cash out of the banks right now. The Department of Homeland Security advises Americans to always have some cash on hand in case of disasters and emergencies. A card linked to an FDIC-insured account won’t be very useful during a power outage, or when a computer glitch or capacity problem brings down electronic payment systems.

The coronavirus reminds us of the fragility in our infrastructure. And so we rebuild some of our banknote balances.

Withdrawing cash from a bank account may also be prudent for those who don’t have FDIC insurance. Since the U.S. dollar is so popular overseas, many countries offer U.S. dollar bank accounts to their customers. A U.S. dollar account in, say, an Angolan bank is not FDIC-insured. And so when the global financial system is under stress, an Angolan depositor has far less security than an American one. Banknotes-in-hand are a much safer option.

We’re still early in this crisis, so who knows what patterns in cash demand will emerge. But for now, cash is filling its normal role as alleviator of uncertainty. To cope with the turmoil, people are withdrawing a bit more of the stuff. And that’s fine!