Policy

Fiscal/Regulatory Policy

Will the rising dollar give rise to calls for more worker protection?

The rapid appreciation of the dollar against other currencies is not a new phenomenon. A look at similar episodes in the past may suggest what policy initiatives might arise this time around if the dollar keeps strengthening.

A previous episode of significant appreciation of the dollar took place from 1995 to 2002. During that period, the dollar index rose over 30 percent. It was a time of rapid globalization, increased outsourcing of American jobs, and, at least until 2001, fairly rapid U.S. economic growth. Both then and now, the dollar’s gains have made the costs of American products and workers climb relative to foreign goods and labor, while extending consumers’ ability to purchase goods made abroad. This tends to lead to increased imports and gives U.S. employers greater incentive to outsource jobs across the border. But the situation today is not quite the same it was in late 1990s.

In the 1990s, the strengthening dollar was only part of the reason for increased labor outsourcing and rising imports. Other forces contributed to the intensifying globalization – most notably, the entrance into the global economy of countries that were previously fairly isolated, from China to Eastern Europe. A number of measures aimed at creating freer trade also were adopted during this period – from North America Free Trade Agreement, which took effect in 1994 to granting permanent normal trade relations with China in 2000.

Among the results of these developments were a significant increase in imports and the movement of jobs overseas. Between 1995 and 2000, imports of goods and services rose to 14.3 percent of GDP from 11.8 percent. While the number of U.S. jobs climbed, spurred by growing output, the prosperity was not uniform. Some industries were hit hard by import competition. For example, payroll employment at U.S. textile mills fell 20 percent from 1995 to 2000, and another 20 percent by 2002.

It is no surprise that workers in the industries adversely affected by these movements opposed many of the trade polices at the time. Various labor unions, from AFL-CIO to the Union of Needle Trades, Industrial and Textile Employees, and Service Employees International Union, opposed deals to expand trade with developing nations. But the unions did not succeed in stopping the free-trade agreements, possibly because the booming economy drowned out their concerns.

It is notable, however, that there were no comparable protests against strong-dollar policies. Even though both those and trade policies contributed to the outsourcing of jobs and the rise of imports, only the trade policies were blamed for it.

It is difficult to say whether the same call for protection against foreign competition will arise today, because the current situation is different from the late 1990s. The U.S. economy is not doing as well today and many developing countries have matured a bit since then. As a result, the same push to outsource jobs is not likely to be repeated. There is no rush of companies trying to establish a presence in countries newly opened to global trade, as was the case in the 1990s. In addition, many emerging economies have evolved to the point that their labor costs are no longer low enough to make moving jobs there from the U.S. so obviously advantageous for employers.

On the other hand, the American economy is not growing nearly as fast now as it was in late 1990s. In 2014, GDP grew about 2.4 percent; from 1995 to 2000, the expansion averaged 4.1 percent per year. The plight of workers being hurt by rising imports might resonate a bit more with the public and policymakers when growth is moderate than when the economy was booming.

Nevertheless, it is highly unlikely that any calls that may arise for protectionist measures, such as tariffs aimed at limiting imports, will succeed. Irrespective of whether political leaders sympathize with affected workers, it is nearly impossible for the U.S. to impose import tariffs, for example. Such an action would violate the rules of the World Trade Organization, of which the U.S is a member. Instead, any reactions are likely to focus on helping affected workers and industries, rather than on limiting trade.

However, it is not obvious that any new policies are needed to protect workers hurt by rising imports. The U.S. has had a program aimed at helping such workers since 1975, called Trade Adjustment Assistance (TAA). It aims to help Americans who have lost or may lose a job due to foreign trade influences. The program provides training, temporary income support, job search and relocation allowances, career counseling, and other resources to assist in finding employment.

With globalization, outsourcing, and rising import competition, one might expect many millions of Americans to use the TAA program. But that has not been the case. From 1995, when globalization really took off, to 2014, only about 3.7 million workers sought assistance under TAA. For comparison, during this period, U.S. manufacturing alone lost over 5 million jobs.

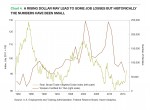

But not all of the 3.7 million workers were eligible for TAA benefits because the Department of Labor first had to confirm that the jobs were indeed lost or threatened by trade-related circumstances. Not all jobs that disappear during periods of rising global trade are lost because of the increase. About 2.7 million workers have met this test since 1995, only a fraction of jobs lost in manufacturing and other sectors often viewed as adversely affected by trade (chart 4).

It might be difficult to argue for additional policies to help workers displaced by foreign competition when their numbers are not particularly large and when a federal program designed explicitly to help them has been in existence for about 40 years.