Expectations under growth and level targeting regimes

In general, I prefer a rules-based monetary policy to discretion, but not all rules are created equally. Today, I want to consider two types of nominal income targeting rules in the hopes of identifying their relative merits for anchoring long run expectations, enabling long run and thereby promoting long run economic growth.

1. Nominal Income Level Target

With a nominal income level target, the monetary authority announces in advance that it will conduct open market operations to hit a given level of nominal income each period. Let’s suppose that the monetary authority thinks there is something special about year-on-year nominal income growth of five percent. That means that, each year, the monetary authority aims to produce nominal income equal to that along the five-percent trajectory.

2. Nominal Income Growth Target

With a nominal income growth target, the monetary authority announces in advance that it will conduct open market operations to hit a given growth rate of nominal income each period. Again, we can suppose that the monetary authority thinks there is something special about year-on-year nominal income growth of five percent. That means that, each year, the monetary authority aims to produce a five percent increase in nominal income.

3. Errors and Long Run Performance

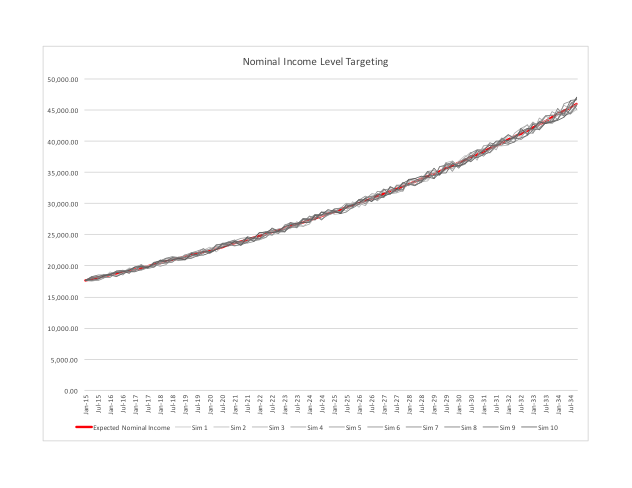

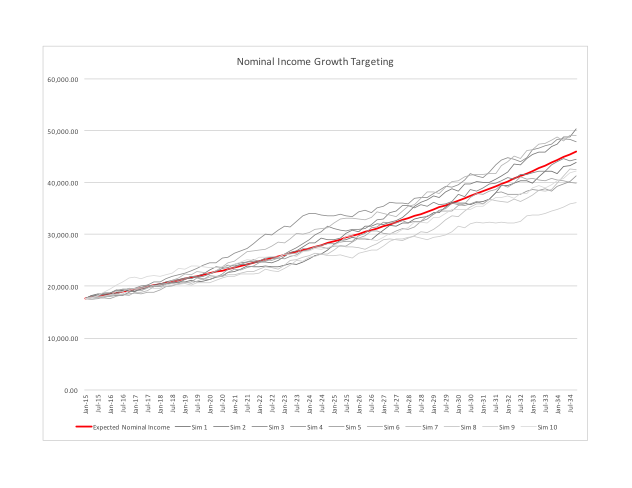

The two policies described above might sound pretty similar. And, indeed, if the monetary authority were to perform perfectly, both rules would produce the same result: a steady increase of nominal income at a rate of five percent per year. The difference between the two rules is only apparent when we allow the monetary authority to make errors. Let’s assume that, in each quarter, the monetary authority might miss its target by +/- 1% of the ideal level of nominal income in that period. These errors are random with a mean of zero. In what follows, I’ve assumed a uniform distribution of errors, but that’s not important for the general point made here. So, how do these two rules compare? Consider the simulations depicted in the following figures. In both figures, the red line depicts expected nominal income at the beginning of the first year the policy is adopted, or, equivalently, the path of nominal income in the absence of any errors. Each grey line depicts the level of nominal income, given the respective rule, for a unique simulation with random errors. (We could produce an infinite number of simulations, but ten are sufficient to make the point.) The level targeting regime is presented in Figure 1. The growth targeting regime is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 1. Simulations of a Nominal Income Level Target

Figure 2. Simulations of a Nominal Income Growth Target

Note that, while both have the same expected path of nominal income at the outset, the level target deviates from the expected path much less than the growth target. This is because, under a level target, the monetary authority aims at the same long run trajectory over time. In other words, the monetary authority has to correct for past errors. Under the growth target, in contrast, the long run trajectory changes each period there is an error because the monetary authority is only concerned with producing the right amount of nominal spending growth each period. It does not attempt to correct for past errors under the growth target. Both rules anchor expectations. If the monetary authority commits to a rule, some possibilities are ruled out. The deviations are limited. However, the nominal income level target provides a much tighter anchor over time.

Under a level target, one can reasonably predict the level of nominal income at any point in the future. The same cannot be said for a nominal income growth target. By providing a tighter long run anchor for expectations, the nominal income level target makes it much easier to engage in long term contracting. You don’t need to worry as much about random monetary policy errors drastically changing the value of your long term contracts under a level target. Under a growth level targeting regime, however, the long run variance can be quite significant. Early errors are amplified through time. As such, you are more likely to engage in short term contracting and short term projects. Since re-contracting is costly and the foregone long term projects are presumably more productive (otherwise, they wouldn’t be foregone), we can be reasonably confident that long run economic production will be lower under the nominal income growth target as compared to the nominal income level target. In summary, while one might prefer rules over discretion, the desirability of even quite similar rules van vary significantly. If we are going to adopt a rule, better to adopt a good one.