The High-Yield Dow Stock Selection Strategy

This an excerpt from How to Invest Wisely. To purchase the book, click here.

We were intrigued by reports of studies that indicated that investing in the highest-yielding of the 30 stocks included in the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) produced consistently superior results. But we questioned the rigor of the strategies we came across. It was seldom explicit whether the transactions and yield calculations were based on the current list of stocks or on the list as it stood at the time decisions would have been made. The rules for trading also were hard to determine. How often were holdings reviewed? Were holdings to be equalized by dollar amounts periodically? How did a strategy deal with buyouts and spin-offs? Etc.

Accordingly, since 1989 AIER has conducted its own studies of the returns from investing in the highest-yielding Dow stocks. We believe our research has been far more extensive than most. We did confirm the major finding of others who had investigated HYD strategies: Investing in the highest-yielding issues in the DJIA generates higher total returns than the Average itself.

To the best of our knowledge, our procedures are unique:

- We review and update the portfolios monthly, using mid-month prices (plus or minus $0.125 per share to allow for trading costs).

- We do not base our results on year-over-year price changes and dividend payments. Rather, we examine the total returns to HYD strategies on the basis of hypothetical portfolios constructed with information that is available at each monthly review: what stocks are on the DJIA list, their prices, and indicated dividend rates.

- Instead of only looking at 12-month intervals, we examine holding periods ranging from one to 36 months. Each month, we purchase the qualified issues in equal dollar amounts and hold them (with any spin-offs) for the full holding period.

- We examine portfolios that range from one composed of only the single highest-yielding stock down through one that contains all 30 on the list. This provides 1,080 possible strategies.

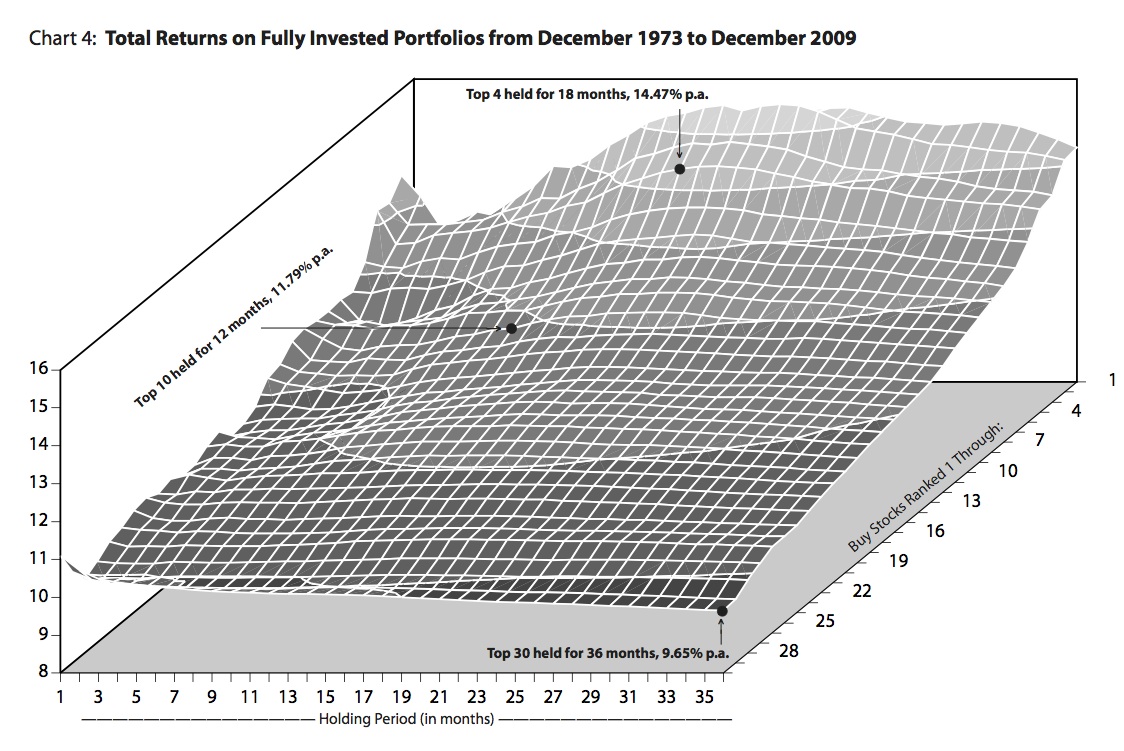

Our studies indicated that the returns could be enhanced further by investing in fewer than 10 issues, and by holding them for longer than 12 months.

We calculated the results of all 1,080 possible combinations. At one end of the range is a strategy that recommends holding the single highest yielding Dow issue for one month. This strategy dictates selling the stock if it falls to number two or lower on the list in the month after purchase or later and buying the new number one issue. At the other end of the range is a strategy of holding all the Dow issues for 36 months, with portfolio changes only reflecting reinvestment of dividends, splits, spin-offs, and the deletion and replacement of issues in the DJIA.

The results of our study for the 46 years ended in December 2009 are shown in Chart 4. We found that the most favorable combination of risk (volatility) and return resulted from purchasing the four highest-yielding Dow stocks each month and holding them for 18 months.

Over the past 46 years, this approach would have provided an annualized total return about 4.8 percentage points more than what an investor would have earned by simply holding the Dow.

The annualized return on a portfolio based on holding the top 4-for-18-months is 14.5 percent compared to a return of 9.7 percent on the DJIA. This is quite remarkable in itself. Only a minority of portfolio managers and mutual funds do better than the stock market averages in a given year, and the proportion who manage to do so over extended periods is minuscule indeed.

But over time the strategy yielded even more striking results. With all dividends reinvested, an HYD portfolio would become more than seven times as large as a DJIA portfolio that was the same size 46 years ago. There is, of course, no guarantee that such a high-dividend yield strategy will accomplish in the future what it would have in the past.

Investments are subject to fads and fashions, with is part of the phenomenon the HYD strategy attempts to exploit. Within the staid universe of the DJIA stocks, a company may become popular or unpopular for reasons that have little to do with its fundamental long-term condition and situation. These behemoth corporations tend to follow conservative and stable dividend policies, and unwarranted fluctuations in investor sentiment are then reflected in their dividend yields.

Our wholly-owned investment advisory firm, American Investment Services, Inc. (AIS) publishes the latest composition of the 4-for-18 High Yield Dow strategy each month in its newsletter, Investment Guide. AIS also manages individual and institutional accounts using this approach.

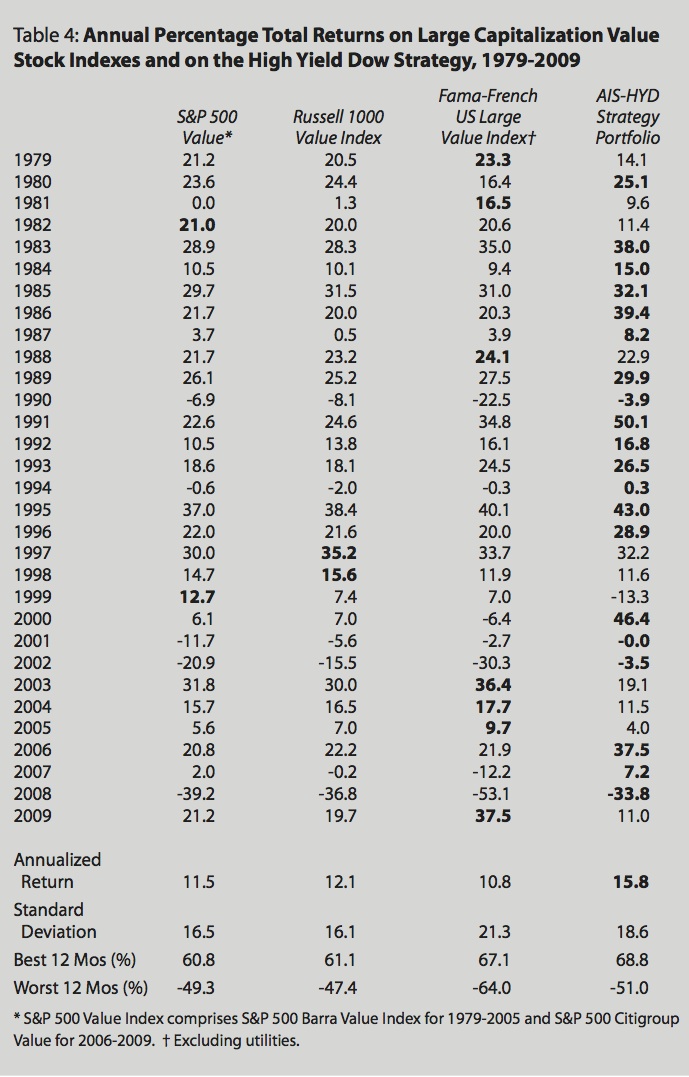

In Table 4, we compare the performance of the 4-for-18 HYD strategy with that of three value indexes that are tracked by mutual funds, the S&P 500 value index, the Russell 1000 Index and the Fama-French Large Cap Value Index. (These results, of course, are before expenses.) Even though the HYD approach does not track any index, like these funds it is a passive strategy because it follows predetermined criteria for purchases and sales.

A Passive Approach

The focus on current yields that the HYD approach relies upon ignores most sources of stock market advice and information. The strategy is based on the conclusions and findings of only three groups: the editors of The Wall Street Journal, who pick major, well-established corporations for inclusion in the DJIA; the directors and managements of the companies themselves who set the dividend payout; and the investing public, who determine the price of the stock. The first two must be considered as more knowledgeable than the third. The editors do not select flash-in-the-pan enterprises for their index. Directors and managers generally do not declare dividends that their companies cannot afford or sustain.

On the other hand, it is the erroneous fashions and foibles of the investing public, including the herd of so-called professionals that the HYD approach is attempting to exploit. The goal of the conservative common-stock investor should be to invest in solid businesses that are undervalued in the marketplace for one reason or another. Fads are most manifest in the brokerage reports, security analyses, rumors, and tips that most investors seem to rely upon in selecting stocks.

Another way of looking at it is that the superior performance of the higher yielding issues in the DJIA is simply another manifestation of the market at work. If the distressed companies that typically offer higher dividend yields are in fact riskier than the high-flying growth stocks that dominate the other end of the list, then it should not be a surprise that the high-yielders provide higher total returns. Greater risk should provide greater returns.

Why Just the Dow Jones Industrials?

The Dow stocks are chosen by the editors of The Wall Street Journal, apparently on an ad hoc basis. As such, they are a very arbitrary selection of U.S. common stocks. Changes in the list are relatively infrequent and have often been forced upon the editors when an issue ceased trading because of mergers or buyouts. In general, the Dow stocks are those of well-known and very large companies. Most of the companies are household names and the Dow stocks are widely held, traded, and followed. Surprises and bizarre financial developments should be few and far between.

No doubt there are many excellent investment opportunities in nonindustrial areas. However, examining the levels of the broad averages (such as those published by the NYSE, S&P, or Dow Jones itself) reveals that the averages for the specialized sectors such as transportation, utilities, and finance are markedly lower than the comparable industrial series. These nonindustrial sections are heavily regulated, and one goal of such regulation is to limit profits and investment returns.

Drawing stock selections from a larger list would necessitate holding many more issues, as many as 100 or more, to deliver a comparable combination of risk and return delivered by the DJIA-based 4-for-18 approach. This would be impractical for all but the largest portfolios. If the selection were to be taken from the top 25 dividend-yielding stocks of the S&P Industrials, for example, it would be likely that at any given time a portfolio would be more heavily concentrated in a given industry. An essentially arbitrary list, the Dow includes only one or two companies in a particular type of business.

More significantly, the top stocks ranked by dividend yield in a larger universe would be far more likely to include companies with managements that, for one reason or another, have not yet faced up to grave problems by cutting or omitting dividends. Focusing on the DJIA stocks means that investments in poorly managed, cyclical, and secondary companies will be minimized.

When a position is sold within a portfolio following a HYD strategy, it is usually because its price has increased relative to its dividend. Occasionally, an issue will be sold because the dividend has been reduced or omitted. Sometimes this means that the position will be sold at a loss. But in some instances, a dividend cut is perceived as evidence that management is forcefully facing up to problems, prompting investors to bid up the stock’s price.

Stable Dividend Policies are the Key

The key to the phenomenon that we are attempting to exploit is that the directors and managers of the companies in the DJIA, as well as most other large, publicly held U.S. corporations, follow a policy of paying regular quarterly dividends. Corporate insiders increase payouts only when they believe that the payouts can be sustained for the long term. This means that the quarterly dividend is an indicator of informed opinion on the long-term prospects of a company. This is not the practice in most of the rest of the world. Even the largest European corporations, for example, typically declare annual dividends according to the year’s results. If they have a good year, they pay a good dividend. If they have a bad year, they do not. The erratic dividend record of General Motors resembles its foreign competitors’ record, and for this reason, we have excluded it from the calculations summarized in Chart 4 and in Table 4. In fact, the dividend yield has not been a useful indicator for trading GM stock. If what we might call the European dividend policy became widely followed among the DJIA companies, the selection strategy probably would not work. There is no sign of this happening. The insiders are under no obligation to declare regular dividends. But their attitude seems to be that their stockholders are mainly widows and orphans, whose major concern is a steady source of income. The dividend policies of smaller and most privately held companies are far more contingent on short-term results: If it was a good year, then the dividend will be good. If it was a bad year, the dividend will be reduced or omitted completely. This is how corporations operated when they were invented. And it continues to be the usual practice for even very large companies in other countries. Where there are large controlling stockholders, their tax situation has usually made it more attractive for them to have the company buy back its stock than increase dividends. This alternative often is followed when large companies have excess funds, and management believes the market price of the company’s stock is undervalued. A second incentive against paying out cash when a company has a good year is that it is in the interest of managers and directors to enlarge the assets under their control, which can have a direct effect on their salaries and fees. During recent years, there have been an exceptional number of dividend cuts among the Dow stocks. Companies have reduced dividends when extraordinary factors rendered previous levels impossible to sustain. Such factors have included sudden, adverse court judgments as well as long-term changes in the structure of industries. The editors of The Wall Street Journal, who select the companies in the DJIA, might be faulted for ignoring these long-term changes and staying too long with poorly managed, burned-out companies. Nevertheless, there is little reason to believe that the increase in the number of dividend cuts reflects a changed attitude among managers and directors. There is no evidence of a systematic trend toward setting dividends to reflect short-term or cyclical results. Much of the enormous expenditures of the securities industry on analysis and research is devoted to identifying growth stocks (shares in companies whose sales and earnings are increasing faster than most). Reputable brokerage firms will usually recommend buying and holding established growth stocks to conservatively oriented long-term investors. One of the characteristics of growth stocks is that they offer relatively low dividend yields. This is because these companies retain most of their earnings to finance expansion, sell at a high multiple of earnings, or because of a combination of these factors. The companies included in the Dow Jones Industrials Average are considered mature enterprises (of the 10 largest companies in the Fortune 500, seven are in the DJIA). Virtually all were growth stocks at one time. And many continue to have superior rates of growth of sales and earnings long after they have been included in the blue chip indicator. Such issues tend to fall in the middle and bottom thirds of the Dow Jones stocks ranked by yield, and they seldom turn up high on the list of issues ranked by dividend yield. A portfolio composed of Merck, Hewlett Packard, Boeing, Disney, Philip Morris, Wal-Mart, McDonald’s, Intel, Microsoft, and Home Depot (all of which have been added to the DJIA since 1972), for example, might well have more than held its own against trading the highest-yielding issues over the past 28 years. However, there are many Lockheeds and Grummans for every Boeing; countless Tastee-Freezes for every McDonald’s. Few analysts, if any, can The High Yield Dow Stock Selection Strategy 75 consistently identify which competitor will prevail in advance. Waiting until a company has emerged from the pack often means buying it just when it is most richly priced and its growth is on the verge of slowing down. Although many fortunes have been built on a buy-and-hold strategy of superior growth stocks, many others have been frittered away in the search for the winners. The HYD strategy is not one of buy-and-hold. Much of its efficacy comes from buying low and selling high. Following a consistent and disciplined program of investing in the highest-yielding Dow stocks means that relatively overvalued issues will be routinely weeded out of one’s holdings and replaced with undervalued issues. An often expressed concern about HYD strategies in general is that they could lose their efficacy if they became widely followed. The simple answer to this concern is that it is most unlikely to happen. One might well call positions in HYD stocks “super-large-capitalization value stocks.” Amazing as it may seem, the market capitalization of the 30 DJIA stocks is more than $3.5 trillion, or roughly 20 percent of the value of all 5,000 or so publicly traded stocks. It would take a very large amount of buying power following HYD strategies to make much of a difference. More fundamentally, any HYD strategy goes against many basic aspects of human nature. Fear and greed are only two of the powerful emotions that can impact investment decisions. Many investors also have “love affairs” with their holdings. Others believe that becoming, or not becoming, a stockholder will have an effect on the company, the natural environment, politics, or the world. The fact is that, for all but the largest and most energetic stockholders, “the stock doesn’t know you own it.” A successful HYD investor need not even have any idea of what the companies do. Very few investors are willing to adopt such an attitude, and we doubt that HYD strategies will ever be followed by more than a tiny minority. Even if an increased popularity of HYD strategies did make a difference, that difference presumably would be to narrow the variation between the higher- and lower-yielding issues in the DJIA. This would diminish, but probably not eliminate, the advantage of an HYD strategy. It always will be possible to rank the issues by yield. There is no reason to believe that the advantage of investing in the highest-yielding stocks would vanish completely. If you check out the highest-yielding issues in the Dow with a full-service brokerage firm, you will probably be told to avoid them: They are where they are because of some sort of tale of woe. Just remember that these are very large companies with assets in the billions and that very often these assets are held in many countries around the globe. The essence of a HYD strategy is to get you to invest in issues that are unattractive to most investors and sell them when they return to favor. The returns of common-stock portfolios that reflect HYD stock selection strategies will be similar. This is because they will hold many issues in common and because all stocks tend to move together over any given time frame. Our studies have indicated that buying the four highest-yielding Dow stocks and holding them for 18 months provided the best combination of return and risk in the past. But there is little reason to believe that this will be the very best approach in the near-term, or even the long-term, future. Variations between one strategy and another will mainly reflect chance, provided the strategies have the following elements in common Once established, the parameters of a given strategy should be strictly followed. Attempts to outguess the market on an ad hoc basis usually fail. You may be tempted, for example, to hold off on the purchase of a stock that meets the criteria you have set for yourself because you have a poor opinion of the company or because it has been the subject of a rash of unfavorable news, Delay for these reasons often means missing an excellent buying opportunity. Similarly, do not succumb to the temptations to sell an issue simply because it has increased in price and is no longer high on the list of dividend yielders. Very often such price moves continue much longer and farther than seemed possible at the bottom.What About Growth

Stocks?

What If

Everyone Did It?

Discipline is

Essential

Read more excerpts from How to Invest Wisely:

As You Prepare to Invest

Active Versus Passive Investing

Why Most Investors Fail

The High-Yield Dow Stock Selection Strategy