Policy

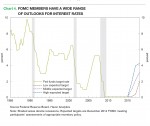

In addition to the ambiguous launch date for raising interest rates, the pace of tightening may also come into question. Throughout the tenure of former Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan, policy moves became predictable, changing by 25 basis points, or 0.25 percentage points, at each of the FOMCs eight meetings per year during the 2004 through 2006 tightening cycle. Should economic conditions remain less than robust and inflation stays below the FOMC’s 2 percent target, interest rate increases may come more slowly in the next cycle compared with the last one (Chart 4).

One other interesting development in the outlook for monetary policy is the pending departures of two regional Federal Reserve Bank presidents – Richard Fisher of Dallas and Charles Plosser of Philadelphia – both of whom are considered among the more hawkish FOMC officials, meaning they are more aggressive in their anti-inflation stance. It’s difficult to say what impact, if any, their departures will have on FOMC deliberations but as of now, the committee appears to be making reasonable efforts to remain balanced in its approach to managing the central bank’s dual mandate.

Fiscal/Regulatory

Cheaper oil amid booming output may lead to lifting long-time ban on exports of U.S. crude oil

The export ban was introduced in 1975 following the 1973-74 oil embargo, which led to quadrupling of the world oil prices. The policy essentially prohibits sending U.S. crude oil abroad, except in a few cases, mainly supplies destined for Canada and crude oil produced in parts of Alaska. But exports of refined products, like gasoline and diesel fuel, are allowed. When the government imposed the ban (and for decades afterwards), the U.S. economy consumed far more oil than it produced, and thus the restriction seemed justified.

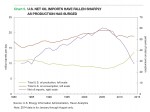

But the situation has changed. The U.S. oil output has soared over the past several years, while net imports have declined (Chart 5.) At the peak in 2005, imports accounted for over 60 percent of total oil consumption. Since then domestic production has risen and consumption declined, and net oil imports have fallen to about 27 percent of U.S. consumption.

One might wonder why the government would consider allowing crude exports when the U.S. still imports oil. One part of the problem lies in a bottleneck in U.S. oil refining capacity. The recent surge in shale-oil production delivers the type of oil for which U.S. lacks sufficient refining capacity. If crude oil producers were allowed to export oil, they would be exporting the crude that domestic refineries are unable to process. By exporting the crude that comes from shale oil, producers could expand their output beyond the constraints currently imposed by the refining capacity. In this way lifting the ban on oil exports is likely to increase domestic crude oil production.

Predictably, producers favor ending the 40-year-old policy blocking crude exports. Their argument centers on the idea that ending the ban would stimulate domestic oil production, create jobs, boost investment and raise incomes. Greater output also may lower gasoline prices for U.S. consumers. This effect would come indirectly, as U.S. exports reduce world oil prices. (The price of gasoline in the U.S. is tied to the global crude price, rather than the domestic crude price.)

Opponents’ argument against lifting the ban is based largely on environmental reasons. Extracting and burning more oil would further damage the environment. Another reason for the ban—energy security—is less pertinent today than it was in 1975. With rapidly rising U.S. oil production, the American public and lawmakers may be less concerned about allowing some crude to head to export markets.

It is possible that proposals to end the ban will gain some traction if abundant oil supplies and low prices persist, making the 40-year policy seem unnecessary. American oil producers want access to global markets and as long as domestic pump prices remain low, U.S. consumers may not object.