COLA to Exceed 2014 Increase

The Social Security Administration’s announcement of COLA usually raises a discussion about how adequately it compensates seniors for the rising cost of living. An answer to this question is less straightforward than it may seem. It has to do with whether the price index on which the COLA is based accurately measures the cost of living faced by retirees.

The COLA is based on the Consumer Price Index for Urban Wage Earners and Clerical Workers (CPI-W), compiled by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. This is different from the Consumer Price Index for all Urban Consumers, the index widely reported as the measure of inflation. In practice however, the two indexes track each other closely.

The Social Security Administration determines the size of the COLA by comparing the CPI-W in the third quarter of the current year to the third quarter of the previous one. Because the CPI-W for the third quarter of 2014 is not yet available, we use a forecast to come up with our estimate. Our expectation is that the COLA for 2015 will be between 1.6 and 1.8 percent. The final data and the official announcement about next year’s Social Security COLA will be released October 22.

There had been proposals, for example by the Bowles-Simpson deficit reduction commission in 2010 and by President Obama in the budget he proposed for 2014, to change the index for computing COLA. Instead of the CPI-W, the proposal is to use the chained CPI. This index usually rises more slowly than does the CPI-W, potentially saving billions of dollars for the federal budget through smaller increases in Social Security benefits for years to come.

The reason for the savings is hidden in the way these two indexes are constructed. The CPI-W averages prices of all the products and services urban wage earners buy, weighting them by the expenditure shares devoted to each. That is, things you buy more of get a bigger weight in the index construction. Information about spending patterns and expenditure shares is collected by a survey every other year. In between surveys, expenditure patterns are assumed to stay fixed.

But people’s expenditure patterns do not stay fixed. Individuals change their buying behavior in response to various factors, including a change in prices. People tend to buy less of the goods that have increased in price and more of the goods with prices that are stable, falling, or rising more slowly. Because of this, the weights used to average many prices into the chained CPI index change every month. And as a consequence, the overall increase in the chained CPI is always smaller than an increase in a fixed-weight index, like the CPI-W.

However, the difference between CPI-W and the chained CPI gets very small when inflation is low, as it is today. If the COLA for 2015 were computed using the chained CPI, the range would be the same—between 1.6 and 1.8 percent.

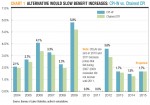

Even though the difference between the CPI-W and chained CPI is small in any given year, over the years the accumulated effect would be a noticeable difference in Social Security benefits. As Chart 1 shows, had the COLAs been based on the chained CPI for the past 10 years, they would be lower every year when there was a COLA. (COLAs were zero in 2010 and 2011 because prices fell during the 2008-09 recession and did not recover for some time.) The cumulative effect of 10 years of lower COLAs would be Social Security benefits about 3 percent lower than they are today.

The average Social Security benefit of a retired worker in 2014 is $1,294 per month. Had the COLAs for the past 10 years been based on the chained CPI, the same average benefit would have been $1,256, which is $39 per month lower. For the substantial number of retirees who rely on Social Security for more than 90 percent of their income, the loss of even $39 a month matters.

There are more than 59 million Social Security beneficiaries, with combined annual benefits exceeding $850 billion. Reducing the COLA by even a fraction of a percentage point can produce substantial savings for the federal budget.

With the federal budget deficits falling in the past several years, the urgency to reduce budget outlays may have subsided. In his proposal for 2015 budget, President Obama no longer included the suggestion for a switch to chained CPI for computing COLAs. But it is likely that the proposal will be resurrected someday. Social Security benefits are one of the largest expenditure items in the federal budget, accounting for almost a quarter of all federal outlays. Shaving off even a small fraction of this expenditure will always be an attractive way to relieve budgetary tensions that are sure to arise in the future.

Ideally, the effect on the federal budget should not be the deciding factor in choosing the method of computing COLA. An accurate COLA would be based on an index that tracks the spending of retirees. Neither the chained CPI nor the CPI-W is based on the spending patterns of retirees, but rather on spending by urban residents of all ages.

An index that comes close to tracking the spending by retirees is the Experimental CPI for Americans 62 Years of Age and Older (CPI-E), which has been compiled by the Bureau of Labor Statistics since 1983. It shows that older Americans spend more on medical care and housing, but less on education, communication, food, and transportation, compared to urban wage earners covered by the CPI-W. Not all people 62 years of age or older are retirees, but this is the only available measure that comes close to reflecting the cost of living retirees face.

According to the CPI-E, older Americans experienced a 1.9 percent increase in prices in the 12 months prior to August 2014. This means that the official COLA, which we estimate to be between 1.6 and 1.8 percent, will fall short of fully compensating seniors for the rising cost of living this year.

The CPI-E has risen faster than the CPI-W in some years and slower in others. Overall, had the COLAs been based on CPI-E for the past 10 years, the increase in Social Security benefits would have been very similar to the increase that actually took place under the official COLA formula even though we observe a difference for this year.

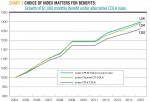

Chart 2 shows the growth of a hypothetical monthly Social Security benefit of $1,000 for the past 10 years under alternative COLA rules. If the CPI-E had been used for COLA computation, a $1,000 monthly benefit in 2004 would increase to $1,294 by January 2015. Under the existing COLA rule that uses CPI-W, it rose to $1,300. Had the COLA been based on the chained CPI, the benefits would increase only to $1,263 by 2015.

The official COLA will be announced by Social Security Administration shortly after the necessary data become available on October 22. Simultaneously, Social Security Administration usually announces changes to other program parameters that are automatically adjusted each year. They include, among others, the maximum earnings taxable by Social Security, currently at $117,000 per year. The increase in this amount is triggered by COLA but not equal to it in size.