Where Did AOC Get Her Sweet Potatoes?

Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez was trying to explain to me that the world is going to melt, we are all going to die, and probably we shouldn’t be having any more children, but I was distracted by the dinner she was preparing on camera. She was carefully cutting sweet potatoes before putting them in the oven.

She put salt and pepper on them. Salt was once so rare that it was regarded as money. Ever try to go a day with zero salt? Nothing tastes right. That was the history of humanity for about 150,000 years. Then we figured out how to produce and distribute salt to every table in the world. Now we throw around salt like it is nothing, and even complain that everything is too salty. Nice problem.

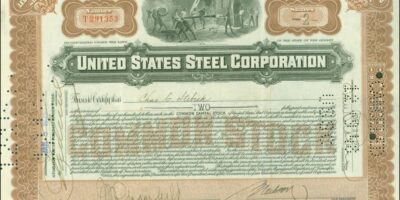

Sweet potatoes are not easy to cut, so she was using a large steel knife, made of a substance that only became commercially viable in the late 19th century. It took generations of metallurgists to figure out how to make steel reliably and affordably. Before steel, there were bodies of water you could not cross without a boat because no one knew how to make an iron bridge that wouldn’t sink.

As for the oven in her apartment, it was either gas-powered or electric. In either case, she didn’t have to chop down trees and build a fire, like 99.99 percent of humanity had to until relatively recently. She merely pushed a button and it came on, a luxury experienced by most American households only after World War II. Now we all think it is normal.

I also presume that her house is warm in the dead of winter and that this is due to indoor thermostatically controlled heat. There are still people alive today who regard this invention as the greatest in the whole course of their lives. They no longer had to work two days to heat a house for one day. Again, one only needs to push a button and, like magic, the warmth comes to you.

The more interesting question is where she obtained those sweet potatoes. The store, I know. No one grows sweet potatoes in Washington, D.C. But where did the store get them? For many thousands of years, the sweet potato was trapped in distant places in South America; it somehow made its way on boat travels to the Polynesian islands, and finally landed in Japan by the late 15th century.

Only once boating technology and capital expenditure for exploration grew to reveal the first signs of prosperity for the masses of people did the sweet potato make it to Europe via an expedition led by Christopher Columbus. Finally it came to the U.S.

But this took many thousands of years of development — capitalistic development — unless you want to see this root vegetable as the ultimate fruit of colonialism and thus to be eschewed by any truly enlightened social justice warrior.

Even early in the 20th century, sweet potatoes were not reliably available for anyone to chop up and bake, especially not in the dead of winter. Today Americans eat sweet potatoes grown mostly in the American South but also imported from China, which today serves 67 percent of the global sweet potato market.

How do we obtain them? They are flown on planes, shipped on gas-powered ocean liners , and brought to the store via shipping trucks that also run on fossil fuels. If you are playing with the idea of abolishing all those things by legislative fiat, as she certainly is, it is not likely that you are going to obtain a sweet potato on the fly.

I admit the following. It drives me crazy to see people so fully enjoying the benefits from private property, trade, technology, and capitalistic endeavor even as they blithely propose to truncate dramatically the very rights that bring them such material joy, without a thought as to how their ideology might dramatically affect the future of mass availability of wealth that these ideologues so casually take for granted.

To me, it’s like watching a person on IV denounce modern medicine — or a person using a smartphone to broadcast to the world an urgent message calling for an end to economic development. It doesn’t refute their point, but the performative contradiction is too acute not to note, at least in passing.

Now to this question about whether there should or should not be a new generation of human beings. After all, she points out, no one can afford them anymore because young people are starting careers tens of thousands of dollars in debt from student loans. She says there is also the moral issue that we need to take care of the kids who are already here rather than having more.

Truth is, she doesn’t really explain well why she is toying with the idea that it is a bad idea that people have kids. Let me suggest that it is possible that she is drifting toward the path of countless environmentalists before her and finally saying outright what many people believe in their hearts: humankind is the enemy. Either we live and nature dies, in this view, or nature lives and we die. There must be some dramatic upheaval in the way we structure society to find a new way. It’s the application of the Marxian conflict fable to another area of life.

Maybe.

In any case, those are big thoughts — too big, really, for a delightful cooking session after which a fancy meal beckons. We’ll get back to what AOC calls the “universal sense of urgency” following dessert.