Three Trigger Points for a Greek-Style Debt Crisis

Editor’s note: the first in this two-part series is available here.

To most people, a Greek-style fiscal crisis in the United States is unimaginable. A Google search on “Greek crisis in America” turns up few results of any substance, with a Congressional Research Service report from April 2017 at the top. However, this report only discusses the international consequences of the Greek debt crisis itself.

The only significant contribution is renowned Cato Institute senior fellow Michael Tanner. In a 2015 column in National Review, he recognizes that Greece has a bigger debt problem than the United States does. However, he explains, if we include unfunded liabilities in Social Security and Medicare, things look quite a bit different. Our pile of liabilities is more than five times our GDP. Greece is in still worse shape — her unfunded liabilities top 875 percent of GDP — but at some point degrees of disaster become pretty much irrelevant.

This is a brilliant observation. Think of it as Tanner’s fiscal-policy version of the mathematical law of big numbers.

In other words, to find the “Greek” breaking point in the US economy, we do not need deficit numbers decades ahead. All we need to do is identify the point where enough creditors perceive the US economy to be as weak as the Greek economy. That happens under three conditions, all of which the US economy could very well meet in approximately six years.

The exact time period from where we are today, to the Greek breaking point depends on the outcomes of the elections in 2018 and 2020. More on that in a moment. First, a look at the three conditions for an US version of the Greek crisis.

Condition 1: monetary policy loses its meaning. This means that the Federal Reserve can no longer supplant private purchases of Treasury bonds. From a fiscal viewpoint, this would replicate the monetary situation that Greece was in after joining the euro zone in 2001.

When then-Fed Chairman Bernanke in late 2008 announced his Quantitative Easing policy, he effectively made the Federal Reserve lender of last resort to the US government. It no longer mattered very much if the Treasury could sell all its bonds on the open market; the central bank vowed to print $700-800 billion per year just to buy those bonds.

Under Bernanke’s QE, the Obama administration never really had to worry about balancing its budget. Even if Janet Yellen began phasing out QE, it had no dramatic effects on the Treasury’s ability to finance its deficits. Were that to change, rendering monetization of deficits practically impossible, then the first condition for a Greek breaking point would be fulfilled. That, in turn, happens when the Federal Reserve loses the ability to keep interest rates down by printing money.

A compound of causes can neutralize the Fed’s interest-rate instrument: persistently higher global interest rates (already underway); a surge in a competing currency, such as the pound sterling (a likely result of a successful Brexit); and an overall rise in inflation (also already underway).

Condition 2: perpetually slow growth. We already meet this condition. As Table 1 shows, we have not had a presidential term with 3 percent average annual growth since Bill Clinton was in office:

| 1948 | 1952 | 1956 | 1960 | 1964 | 1968 | 1972 | 1976 | 1980 |

| 5.1 | 3.8 | 2.6 | 3.9 | 5.6 | 2.9 | 2.6 | 4.7 | 1.3 |

| 1984 | 1988 | 1992 | 1996 | 2000 | 2004 | 2008 | 2012 | |

| 4.6 | 2.4 | 3.3 | 4.4 | 2.4 | 2.9 | 0.3 | 2.3 | |

| Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis | ||||||||

Forecasts for the foreseeable future place average growth rates anywhere between 1.9 and 2.9 percent, though the balance tends toward the lower number. Without structural spending reform, it would take many years with 3.5-4 percent growth just to close the federal budget gap. With growth rates likely in the 2.5 percent neighborhood (taking account for the GOP tax reform), deficits will persist, and the debt will continue to grow.

It is worth noting that the Greek economy grew at 3 percent or more for at least a decade before the crisis.

With growing debt comes growing interest costs. With a $20-trillion debt, 2 percent is $400 billion, equal to the budget for the US Department of Health. At 4 percent, interest payments claim two health departments. When slow growth conspires with higher interest rates, the debt becomes a critical budget item.

To avoid a default under high interest rates, Congress will have to make budget priorities of a kind Americans have never experienced (nor had the Greeks, prior to their crisis). Failure to act fast enough will rapidly raise the prospect of default on debt payments — and drive interest rates up even more.

Condition 3: more entitlements. As absurd as it may sound, the federal budget as it looks today is unlikely to generate a Greek-style crisis. However, that can change, and change fast, if Democrats win back Congress. When they do, they will quickly push for three new programs to be added to the roster of federal entitlements: single-payer medical care, general income security, and universal child care.

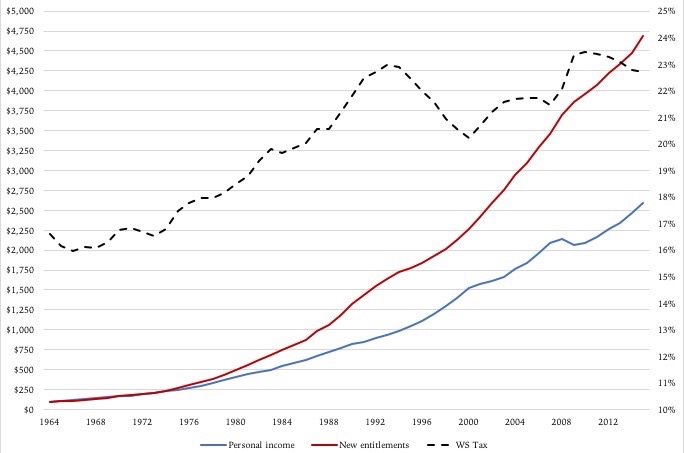

Figure 1 illustrates what would have happened if these three entitlement programs had been introduced as part of the War on Poverty in 1964. The red function marks the total costs of the programs, in current prices,* while the blue function reports personal income, the likely tax base for these entitlements. The dashed function represents the tax rate on personal income needed to pay for the three programs out of personal income:

(Sources: Bureau of Labor Statistics and Bureau of Economic Analysis)

The entitlement programs simply outrun their tax base, forcing Congress to continuously raise taxes — or run increasingly excessive deficits.

Keep in mind that this simulation is based on real, historic personal-income data, which in turn reflects a high-growth economic environment. As a result, tax revenue grows faster in this simulation than it would in a future, low-growth economy. In fact, the introduction of single-payer medical care, general income security, and universal child care would likely lead to a deficit explosion within only a few years.

Therefore, it is conceivable that these programs, were they launched in 2020, would increase the federal deficit well above $1 trillion (assuming the current federal deficit remains). Furthermore, it is entirely possible that this would happen within one presidential term.

Under this scenario, with all three conditions for a Greek crisis fulfilled, Congress would find itself having to choose — and choose fast — between a tax shock and a deficit explosion.

Either way, confidence in the US government’s ability to control its finances would be lost. The Greek breaking point would become reality.

*The cost of these three entitlement programs is calculated according to a formula developed by the author. For more information, please contact the author through the American Institute for Economic Research.