How E.C. Harwood Stood Firm Against FDR’s Attempts to Censor AIER

Many ongoing “speech controversies” of the modern era involve a certain amount of tension between ostensibly private actors – media outlets, tech companies, universities – and the freedom of expression. While we must acknowledge the right of private entities to chart their own rules of content and expression in their respective fora, recent congressional hearings amply demonstrate that political actors are often lurking closely in the background of these controversies, ready to nudge the private sector toward censorious design.

Free speech is more than just a political right. It is a desirable social norm that sustains and promotes a culture of tolerance around the free and open exchange of ideas, even if we find some of those ideas objectionable. When the pressures of the state align against free expression, even indirectly and through private actors, it imperils this norm.

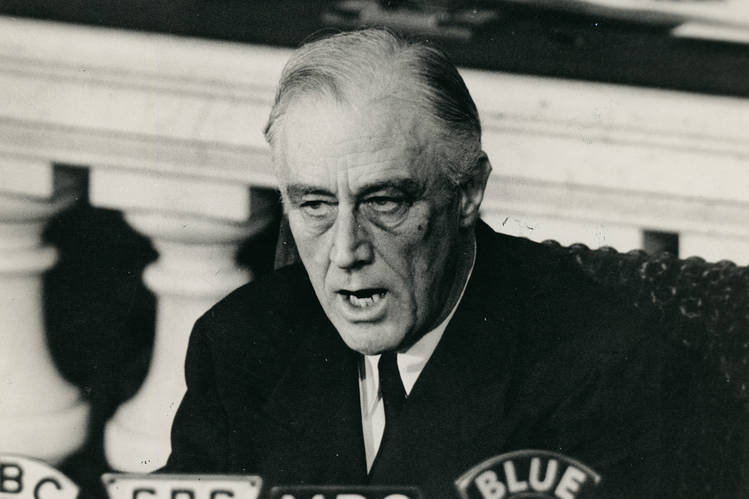

Unfortunately, the United States government has a long and sordid history of applying pressures to silence disliked political speech. One such episode actually threatened the existence of AIER itself in its infancy, when our founder E.C. Harwood ran afoul of the New Dealer economic designs of Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

Censored!

With a war raging in Europe and the storm clouds gathering around the United States, several of Harwood’s former commanders convinced him to resume active duty as an officer in the Army Corps of Engineers in August 1940. They would need experienced and trusted engineers should the U.S. enter the war. Harwood accordingly took a leave from his teaching position, named Donald G. Ferguson as the Acting Director of AIER in his place, and reported for duty at the Army Corps of Engineers in Boston.

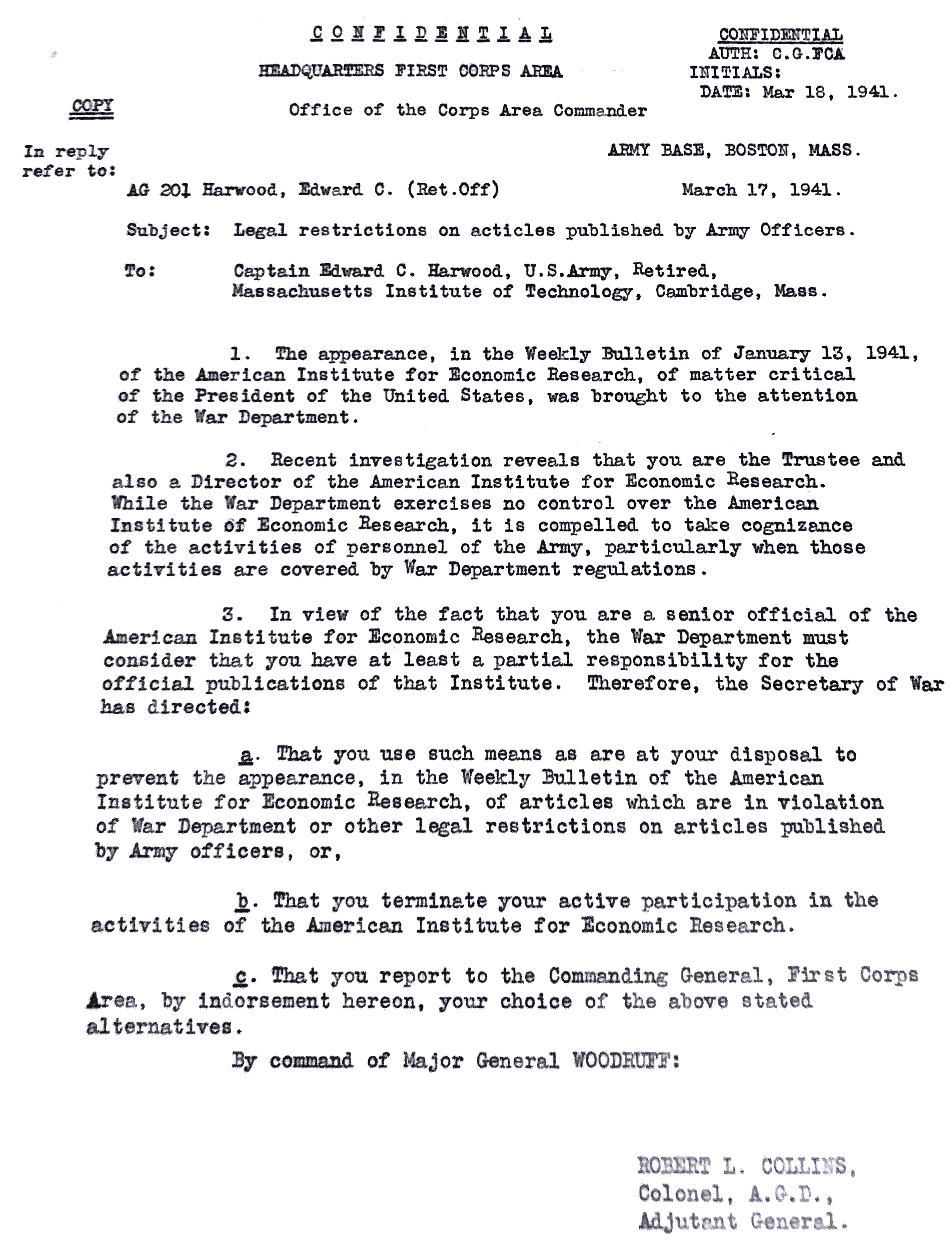

Shortly thereafter in March 1941, Harwood received an unexpected visitor from Washington. The Adjutant General’s office was opening an investigation of him over “the appearance, in the Weekly Bulletin of January 13, 1941, of the American Institute for Economic Research, of matter critical of the President of the United States.” Since Harwood still remained a trustee of AIER, the War Department considered this position subject to military rules governing the political activities of soldiers:

“In view of the fact that you are a senior official of the American Institute for Economic Research, the War Department must consider that you have at least a partial responsibility for the publications of that Institute. Therefore, the Secretary of War has directed:

a. That you use such means as are at your disposal to prevent the appearance, in the Weekly Bulletin of the American Institute for Economic Research, of articles which are in violation of War Department or other legal restrictions on articles published by Army officers, or,

b. That you terminate your active participation in the activities of the American Institute for Economic Research.”

Although Harwood had placed editorial control of the Bulletin under Ferguson during his absence, this novel interpretation of army rules had an ulterior political design. Fully knowing that Harwood’s resignation from the institute he founded was not an option, the government intended to leverage his wartime officer’s reactivation as a tool for silencing AIER’s long-running criticisms of New Dealer economic policy.

The political persecution of Harwood appears to have originated in the highest ranks of the Roosevelt Administration. As Harwood later recounted, an investigator showed him a copy of the Bulletin containing a handwritten directive to “investigate and stop this.” It was signed by Lauchlin Currie, a former Harvard professor who became Roosevelt’s chief adviser on economic affairs in 1939.

Who Was Currie?

A prominent New Dealer in his own right, Currie was one of the main architects of Roosevelt’s Banking Act of 1935, which centralized the Federal Reserve’s organizational structure and expanded its ability to use open market operations for monetary meddling.

Currie was a consummate central planner, using his position at the White House to push for aggressive expansions in entitlement spending, public works programs, and centralized economic design. His public service career ended in disrepute after the war when investigators learned he was working as a spy for the Soviet Union. In short, Currie was a living antithesis of Harwood’s economic philosophy.

Harwood saw right through the bureaucratic formalities of the War Department’s investigation and recognized a blatant attempt by the White House to silence one of its economic critics. In a lengthy written response, he detailed the steps he had taken to “discontinue…my work there except that related to the duties of Trustee,” a strictly fiduciary position, for the duration of his return to active duty. The institute’s daily operations were handed over to its faculty at this time under the terms of its nonprofit charter. “It is not my personal property,” Harwood answered, “nor is it subject to my orders.”

Calling the government’s bluff, he offered to resign his trusteeship at AIER or accept being relieved from active duty so that he may return to private life. “My only concern at the present is to be of help to those whom I have undertaken to serve during the emergency” of the looming war.

In doing so, Harwood likely recognized that his personal status was of little consequence to the White House. Rather, they wanted to leverage his return to active duty as a tool for censorship over AIER, as proposed by the investigator’s memorandum. Unsatisfied with the offer to resign, the investigator pressured him to instead reveal the authors of each article criticizing Roosevelt in the Weekly Bulletin.

Harwood stood firm, noting that “if I choose to reply to questions of this character, I shall inevitably narrow the field of responsibility for authorship of the material and facilitate what in effect will be the persecution of a limited number of other people” on AIER’s faculty. “My present belief is that it would be wholly improper for me to participate, even directly, in any such proceedings.”

One of Four

Turning the tables on the government, Harwood next enlisted Roosevelt’s own words to reveal the hypocrisy of the White House’s efforts. Only a few weeks prior, Roosevelt delivered his famous “Four Freedoms” address to Congress, highlighting the growing threat of Nazi Germany from across the Atlantic. In Roosevelt’s telling, “The first is freedom of speech and expression – everywhere in the world.”

In declining the government’s “solution” of using him to censor AIER on their behalf, Harwood retorted “It is my intention always to refrain from any action that may directly or indirectly lead to a thwarting of this great aim” that had been “so recently discussed by the President.” In a likely jab at Currie, Harwood continued:

“I have often wondered, since the first investigation of this character, what the source of the investigation could have been, and have assumed that it was politically inspired by immediate subordinates of the President without his knowledge. In view of his own recent assertions, I cannot believe that he would authorize or permit such proceedings; therefore, until I receive definite evidence to the contrary, I shall assume that the position I have taken is in accord with the wishes of my Commander in Chief as well as the dictates of my own conscience.”

It was an effective rhetorical move that brought the ethical implications of the government’s investigation into full view. Historians have since documented that similar persecutions of free speech and the free press were in fact a norm of the Roosevelt administration, including with likely acquiescence from the president. Still, Harwood provided a powerful reminder of the importance of the ideal that Roosevelt spoke of in his speech.

The Adjutant General’s investigation reached an impasse in the following weeks as Harwood conveyed his position to the AIER staff, and announced his intention to hold firm against the censorious demand. Ferguson answered on behalf of the institute, noting that Harwood had left his directorship in their care during his military activation and withdrawn from its daily activities.

As Ferguson explained “We…suggest that, if the War Department desires to censor the Research Reports, it submit a statement of its wishes and the legal grounds therefor directly to the Faculty of the Institute rather than through an intermediary,” Harwood during his return to active duty, “who has neither personal responsibility nor authority with respect to the Research Reports.”

And with that, the War Department appears to have dropped its demands.