Financial Depth and the Fed’s Balance Sheet

Monetary economists have spent the better part of the past decade considering the Fed’s bloated balance sheet. Does a large balance sheet enable effective monetary policy? Should the Fed sell off its assets in a return to normalcy? Often overlooked in this discussion, however, is the effect a large balance sheet might have on bank lending and real economic growth. Both have been sluggish since 2008. Perhaps the Fed’s $4.5 trillion balance sheet is partly to blame.

The financial systems plays a critical role in the process of economic growth. Arguably the most important channel through which finance contributes to growth is through financial deepening, or the extent to which the private sector allocates credit. The intuition is straightforward. Private financial institutions specialize in channeling savings into profitable, productive investments. These investments lay the foundation for sustained economic growth and development. As such, the share of private bank-issued money in the economy provides a reasonable estimate of financial depth and, the higher the ratio, the greater the prospects for real economic growth.

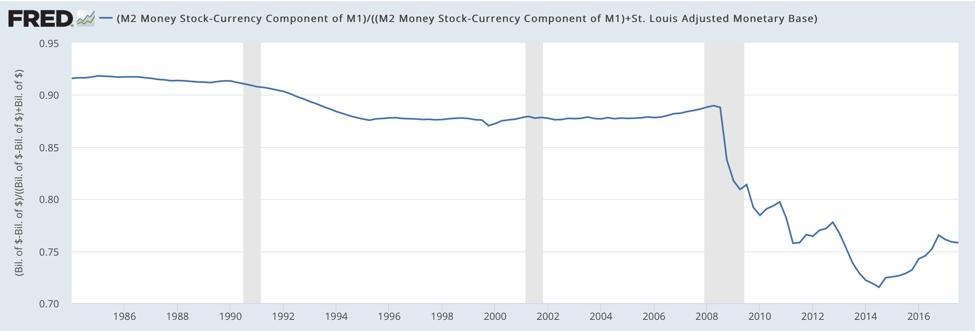

Unfortunately, this ratio has declined rapidly in the United States since 2008Q4, when the Fed began expanding its balance sheet. For the decade prior, financial depth in the US averaged around 87.89 percent. Since 2008Q4, it has averaged just 76.24 percent. Although there are many contributing factors, the Fed’s policy of paying member banks interest on excess reserves is perhaps chief among them. Simply put: the Fed has encouraged banks to hoard excess reserves rather than make loans. Economic growth has suffered as a result.

What kind of assets is the Fed holding? As of December 2017, just over half (54.69 percent) of the Fed’s balance sheet consists of U.S. Treasury securities. Mortgage-backed securities make up another sizeable chunk (39.42 percent). Together, these two categories account for 94.11 percent of the Fed’s asset holdings – not exactly a potent recipe for a healthy and vibrant economy.

The Fed’s massive balance sheet is almost certainly crowding out private investment – private investment that would fuel economic growth. Moving forward, we must recognize the important role private financial institutions play in greasing the wheels of the economy. A bloated balance sheet gets in the way. The Fed should shrinki its balance sheet. As the share of private bank-issued money in the economy returns to more reasonable levels, so too will the rate of economic growth.