Endangered Species: States without Income Tax

What do Alaska, Connecticut, and Wyoming have in common? They have all tried to get by without an income tax. Soon, Alaska and Wyoming may do what Connecticut did in 1991: start taxing income.

While President Donald Trump’s federal tax-reform plan promises tax cuts for the middle class, taxpayers in some states may see their total tax bill go the other way. Recently, the Kansas Legislature reversed its 2012 tax cuts, which were part of a long-term plan to eliminate income taxes in the Sunflower State.

In September, Alaska Governor Bill Walker proposed a “payroll tax”, an income tax by another name. His state is a step ahead of Wyoming, where the legislative leadership is working hard to get a de facto income tax through the 2018 legislature. Technically, the Cowboy State’s new tax could be levied on “gross receipts” or “general revenue,” but from a practical viewpoint both terms are basically synonyms for income.

The fight over state income taxes is as old as state taxation itself. For example, New Hampshire lawmakers and governors have been debating the issue for decades. While the tax proponents in the Granite State have not yet gotten what they want, in 1991 their peers in Connecticut celebrated victory when Governor Weicker signed a state income tax into law. It would, he said, close the book on the state’s fiscal past and help Connecticut face the future.

Similar arguments are being made in Alaska and Wyoming. Do taxpayers in those states have good reasons to believe that their states will face a brighter fiscal future with a new tax on the books?

Probably not. The Connecticut income tax, which started out at 4.5 percent, was sold as the bridge that would solve the state’s Gordian knot of a budget mess. That did not happen. By 1993 the income tax was the state’s second largest revenue source, exceeded only by funds from the federal government.

By 2000, when the income tax was on its 10th year, revenue had almost doubled from 1993. At $4 billion it brought in more than one in five revenue dollars, easily making it the largest revenue source for the state of Connecticut.

Despite an annual increase in income-tax collections of 8.6 percent per year, the legislators in Hartford plunged Connecticut back into unending budget problems. After having helped the state run a surplus of seven percent in 1994, the income tax became just another motivator for state spending. By 1998, the state spent almost 14 percent more than it took in.

As a testimony to the permanent nature of the budget problems in Connecticut, in May last year Forbes Magazine columnist Rex Sinquefield explained:

Just last week, the state’s General Assembly passed another budget that cuts services while continuing to spend more money. (The budget is so ill-conceived that it prompted credit downgrades from Fitch and Standard & Poor’s.) Anyone with a passing knowledge of Connecticut’s fiscal woes knows this is just the latest in a long line of bad decisions made by the state’s leadership. Connecticut’s irresponsible spending makes it an unappealing place for many families and businesses, and high taxes prompt alarming levels of outward migration. According to an analysis by the Yankee Institute for Public Policy, Connecticut’s out-migration causes the state to lose $60 of income every single second.

On September 16 this year, the Hartford Courant referred to the state’s fiscal situation as “chaos” caused by a pressing for steep spending cuts.

In short: an income tax does not solve a state’s budget problems. On the contrary, it opens yet another spending faucet. Government continues to grow, from which arguments arise for even more, even higher taxes.

Over time, a state’s economy suffers. In a piece for the Heritage Foundation in 2014, economist Steve Moore reported on a comparison between two low-tax states, Florida and Texas, and two high-tax states, California and New York. The comparison looked at jobs creation and stretched over 25 years, 1990-2014:

Here are the results: Texas, up 65%; Florida, 46%; entire U.S., 27%; California, 24%; New York, 9%. The Texas jobs growth rate exceeded California’s by more than 2.7 to 1. (Weather doesn’t explain that, nor does the oil-price spike, because California is also one of the largest oil-producing states.) The Florida growth rate exceeded New York’s by about 5 to 1. Florida had almost double California’s job growth rate.

Plain and simple, jobs migrate to where taxes are low, away from where taxes are high.

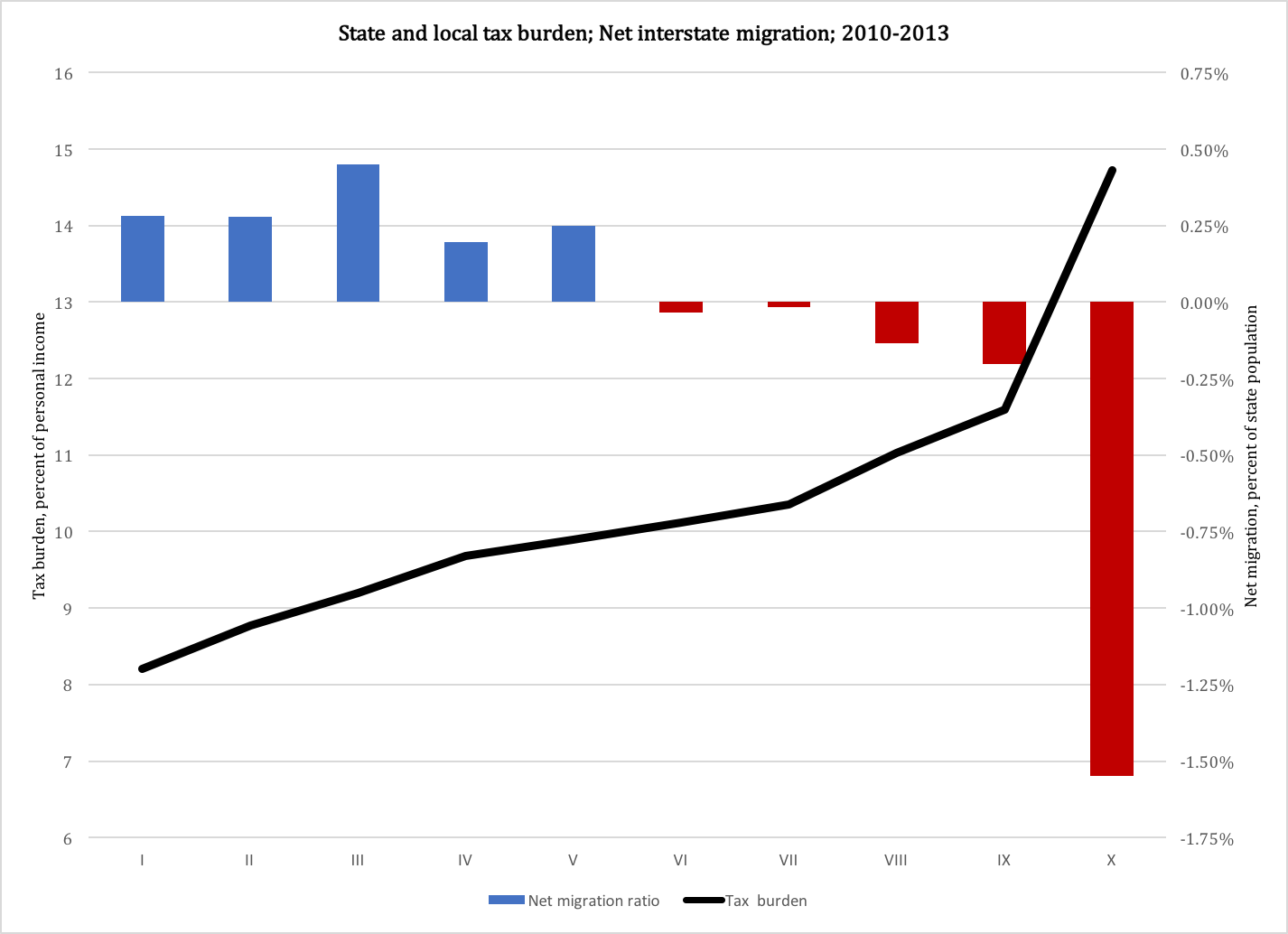

And people follow. The following figure compares interstate migration data from the Census Bureau with the tax burden on personal income (as reported by Key Policy Data). The columns report net migration flows, added up across the 50 states, over the period 2010-2013. The numbers are divided into deciles, by net migration flow as share of the state’s population.

The black line in the figure reports the tax burden. For example, states that fell into the first decile (for one or more years) saw, on average, a net immigration of people equal to 0.3 percent of their population. The tax burden for those same states was 8.2 percent of personal income.

By contrast, in the tenth decile, states averaged an outbound migration of 1.6 percent of their population and had an average tax burden of 14.7 percent of personal income:

Generally, the data presented in Figure 1 suggests that so long as a state’s tax burden stays below 10 percent of personal income, its migration flow is positive. Once the tax burden exceeds 10 percent, the migration flow switches from inbound to outbound.

Legislators in Alaska and Wyoming should take these numbers very seriously. Together with Florida, Nevada, South Dakota, Texas, and Washington, they are two of only seven states that do not tax any personal income. In New Hampshire and Tennessee, only work-based income is tax free. Even if a new tax is called something else, so long as it taxes earnings of any kind (payroll, gross receipts, general revenue) it is for all intents and purposes an income tax.

A better idea would be to start downsizing government to fit inside the narrowing tax base that taxpayers can afford to provide.

Image: Sven Larson. Data: Census Bureau (interstate migration) and Key Policy Data (tax burden).