Amid California Drought, Almonds Defy Economic Gravity

Georgia is an intern from Monument Mountain High School in Great Barrington, Massachusetts. She plans to study International Relations and Asian Studies in college beginning this fall.

Over the last several years, an ongoing drought has caused changes in California’s expansive agricultural economy. But a curious event has happened during this drought. Almonds require more water than many other crops in the area, and yet they are gaining a larger and larger share of agricultural production. This does not fit neatly with economic theory.

California produces nearly half of the fruits, nuts, and vegetables grown in the United States, and over 90 percent of almonds, artichokes, garlic, celery, and walnuts consumed in the U.S.

But as of March 2015, an estimated 97 percent of California’s agricultural sector faced severe, extreme, or exceptional drought, according to the USDA. With agriculture generating around $43 billion in revenue per year, the California drought is a serious concern for farmers and consumers alike. One would imagine these are not ideal conditions in which to grow a crop’s market share.

The Central Valley of California is typically one of the world’s most productive agricultural regions. More than half of its agricultural revenue comes from its San Joaquin Valley area. Since the 1930’s, the dams and levees built to redirect water and prevent flooding of the plains have prevented the natural flow of water into the San Joaquin Valley, requiring farms to import water from the north.

With low precipitation levels for the past four years throughout the state, farmers are estimating the cost, and are planting higher-value crops. As of November 2015, the drought conditions for the San Joaquin Valley showed a year-to-date rainfall of 1.9 inches, compared with an average rainfall of 11.5 inches there over the last 30 years.

Economists at California State University estimated the drought would cost the agricultural system in the San Joaquin Valley $3.35 billion in 2015. Although the price of water is complicated and subject to state regulation, the price has risen substantially in the past few years. The Fresno-based Westland Water District, which represents 700 farms within the San Joaquin Valley, sold water for $1,100 per acre-foot in 2014, an alarming increase from $140 in 2013. Many farmers have resorted to drilling their own wells for a one-time cost of $300,000-350,000, or deepening their existing wells. The cost of these wells further adds to the cost of production of fruits, nuts, and vegetables each year.

To maintain revenue and profits, economic theory would predict that farmers might do one of two things in response to the massive increase in production costs. One, we might expect that farmers would choose less water-sensitive crops in order to reduce production costs and maintain profit margins without significantly driving up the consumer price. Or, farmers could try to pass the costs onto consumers. But if that were to happen, we would expect demand to decrease as prices rise, leading to an equilibrium that would see a greater production of less water-sensitive crops. Of course, theory predicts this decrease in demand, when “all other things are equal.”

Despite the severity of the drought, farmers are actually producing more almonds, and allocating more farmland to the water-thirsty nuts at an ever quickening pace. That tells us to look for what has changed. The massive costs associated with almond production are being entirely passed on to the consumer, yet demand is not slowing down. San Joaquin Valley’s $6.5-billion almond industry is booming.

The San Joaquin Valley provided 99 percent of the United States’ commercial supply of almonds and 80 percent of the world’s supply on only 870,000 almond bearing acres in 2014, according to the USDA. That’s despite a 16 percent increase in production costs in four years, from $3,897 per acre in 2010 to $4,540 in 2014, according to an analysis by the Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics and the University of California.

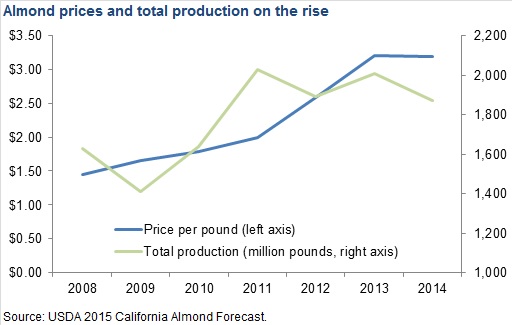

Those increased production costs have been passed onto the consumer in local grocery stores across the United States. Almonds cost $1.48 per pound in 2008, before the drought began. The cost increased to $3.19 in 2014, an annual increase of nearly 14 percent:

And yet, people are paying. In an article by the Washington Post the United States craving for almonds has “grown by more than 220 percent since 2005 — far faster than demand for pecans, walnuts, macadamias, pistachios, cashews, or peanuts.” Almonds have grown in popularity overseas especially in China, Hong Kong, and Germany, where heavy marketing and many favorable reports encapsulate the nut’s many health benefits.

While the drought continues into 2016, California farmers allocate even more land to almonds, only exacerbating the water issues and contributing to the increase in almond prices.

California’s almond boom has sparked a discussion over the amount of water required to grow these nuts. A single almond requires about a gallon of water to grow, and with residential water restrictions to decrease cities’ dependency on water, farmers have been doubling amount of acreage devoted to water. In an article by Mother Jones, “The amount of water that California uses annually to produce almond exports would provide water for all Los Angeles homes and businesses for almost three years.”

The fact that people are still willing to pay the much-higher cost speaks to the voracious appetite of the consumer for almonds. And producers are willing to do whatever it takes, as long as consumers are willing to pay for it.