A Greek Tragedy on the Horizon

Editor’s note: the second in this two-part series is available here.

Now that we know what the Republicans want for tax reform, and that this reform won’t make much of a difference for the federal budget deficits, the next big question is what the fiscal and macroeconomic future looks like for the United States.

At this point, a scenario opens up where it is no longer unrealistic to ask: how much more debt can the US government accumulate before the country is hurled into a debt crisis?

The question is all the more important for two reasons:

a) Federal spending is only going to rise, even in real terms: the Trump administration has been flirting with the idea of a new, big federal entitlement program called “paid family leave,” and Democrats are showing strong support for single-payer medical care;

b) the Republican tax reform is founded on unrealistically high GDP growth expectations.

In fact, more, new government entitlements will depress economic growth — government spending over 40 percent of GDP permanently slows down GDP growth — thus widening the gap between reality and projections in the Republican tax reform.

In the past century, the industrialized world has seen many “mild” examples of debt crises, where countries have gone through varying forms of austerity in an attempt to curtail deficits and repair an urgent loss of credibility on international financial markets. Those episodes, which mostly took place in European welfare states, came and went without much fanfare. However, three more serious debt crises have left footprints in recent memory: Sweden in the 1990s, and Argentina, Puerto Rico, and Greece in the past 10 years.

Of these crises, the one in Greece has earned global notoriety, and for good reasons. An advanced nation, economically marred by debt, plunged from the global heights of prosperity into a shadowland in stagnation and industrial poverty. The decline and fall of the Greek nation, which lost one quarter of its economy in the process, is reminiscent of what happened in Germany in the 1920s.

While the Weimar Republic has become known for its hyperinflation, the common denominator between them is really the unforgiving application of fiscal austerity as a means to control deficits and debt. In the German example, the reason was external in the form of punitive reparations due to World War I.

In Greece, however, the debt crisis had entirely domestic causes. In fact, a closer look at the downfall of the Greek economy can give us a good idea of what could happen here in the United States. There are some important differences, of course — for example, the Greek economy has never been bigger than a mid-size US state, and it is subject to a supra-national currency — but the similarities are also strong.

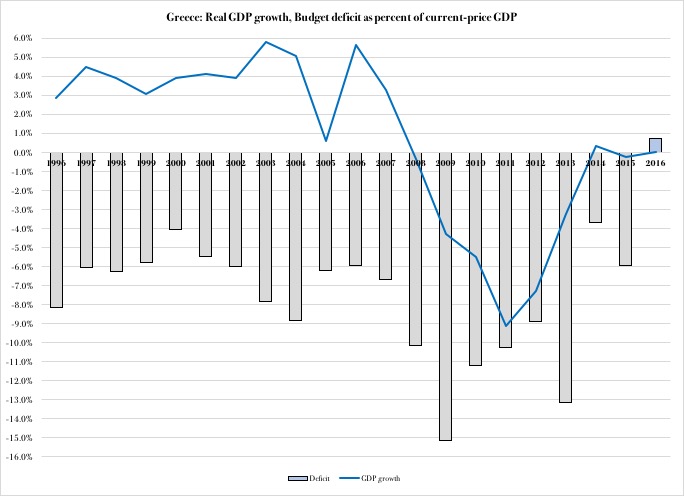

To begin with, the Greek debt crisis was not caused by poor economic performance. As Figure 1 explains, in nine of the 10 years preceding the 2008 start of the crisis, the Greek economy grew at more than 3 percent (blue line). The problem was instead an unrelenting streak of deficit spending (columns):

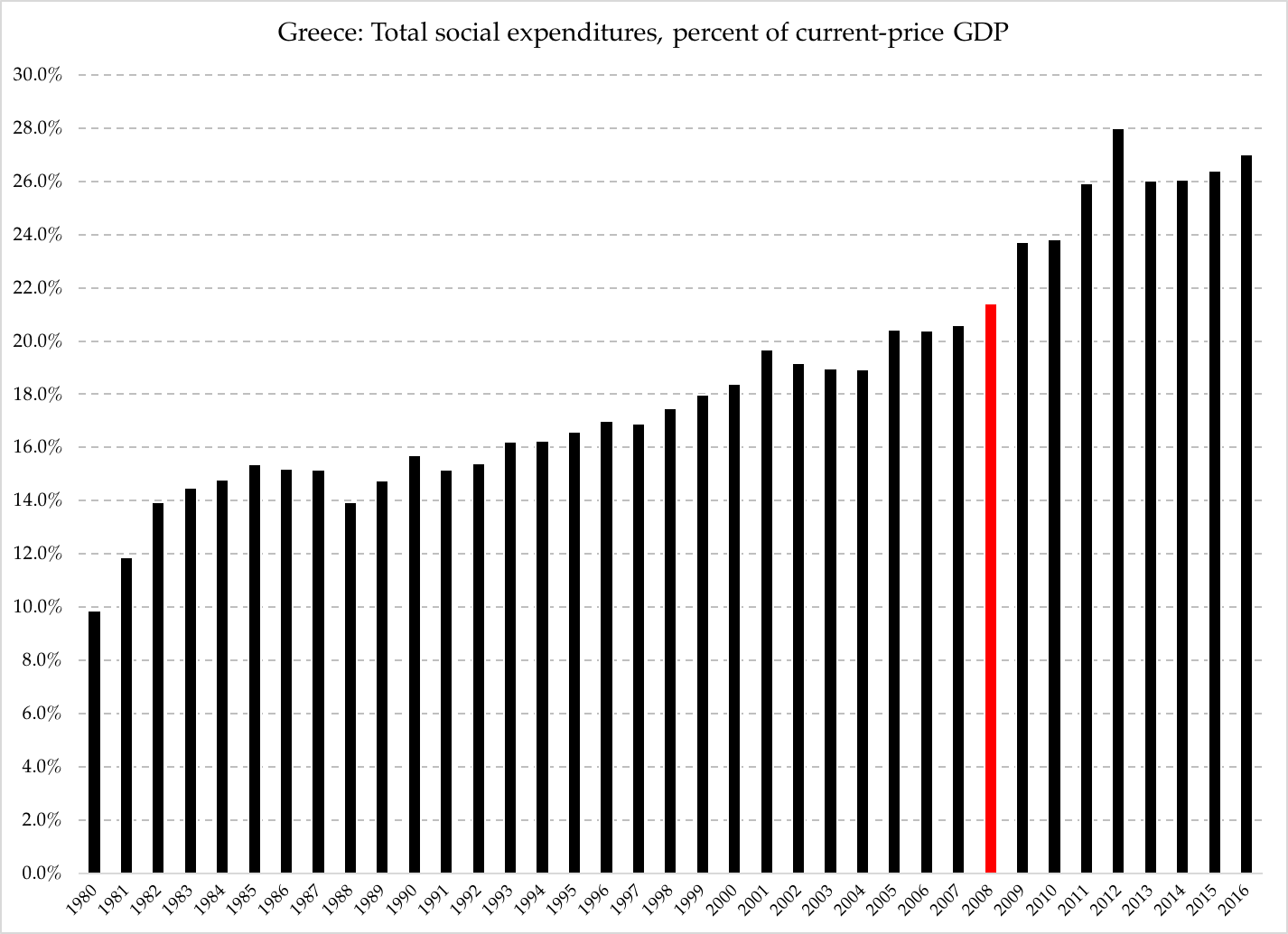

The deficits in the Greek government budget were driven by relentlessly growing entitlement spending. The growth, in turn, took place over a long period of time. From 1988 to 2008 (the red column) entitlement spending grew from 13.9 percent of GDP to 21.4 percent:

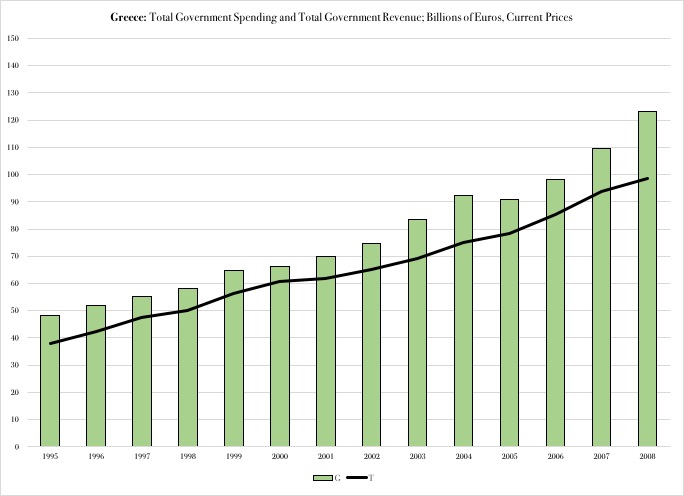

Looking directly at the Greek government budget, the relentless growth in government spending stands out even further as the driver of deficits. In a scenario that is eerily reminiscent of US government finances, tax revenue in Greece kept growing at rates comparable to spending, just not at a rate that caught up with government spending. Looking again at the 10 years immediately before the crisis outbreak, tax revenue growth exceeded 7 percent per year; as Figure 3 explains, that solid growth rate was outpaced by government spending:

It is, again, easy to point to differences between the United States and Greece that reduce the relevance of the Greek example. However, when it comes to the fiscal core of the crisis, Greece exhibits striking similarities with the current US situation that warrant a closer comparison between the two countries.

In the next installment we will take a closer look at just how informative the Greek crisis is in predicting how far away into the future a US debt crisis could be. Such a comparison is difficult to make, of course, especially when stretching out into the future. That said, policy decisions today, on government spending, taxes, and other economic policy variables, cannot rely solely on hindsight. They have to stand on predictions of a more or less predictable future.