Why Your White Clothing Is No Longer White

I’m sitting here today wearing the whitest shirt that’s been on my back in years. My collar matches. It wasn’t easy. It took a good part of the day. It’s the culmination of years of trial and error to achieve what decades of government regulations have tried to prevent.

In a bit, I’ll tell you how I achieved this, revealing every secret.

First some background.

Speaking at a Caribbean island this year, I was notified of a “white party” one night. I had never heard of this. Everyone must wear white, all the way to the shoes. I scrambled to buy some clothes, and I’m glad I did. The entire beach was filled with people wearing white, while the lights of the event were an ultraviolet hew. The effect was glorious.

But then again, this was an island that still knows how to get clothing white. In the United States, we seem to have nearly given up. This party would not have worked here for the reason that white clothing hardly exists — really white, bright white, blindingly white.

Back in my childhood, vast numbers of laundry commercials were about how this or that product would make your clothing white. These days, not so much. Look around at your friends and coworkers. Either they are not wearing white or the whites are vaguely dull and unimpressive.

What has changed? All the essential tools for making clothing super white have been deprecated, mostly by government regulations.

The water in our homes is no longer very hot because government regulations nudge us to use low-performing water heaters. It needs to be 140 degrees, whereas most “water heaters” come with 110 degrees as the default.

Our washing machines don’t use much water at all, thanks to “high efficiency” standards that load from the front. You can’t truly clean without lots of water.

Our laundry detergent no longer contains phosphates, which means that the soap stays in the clothing, making them ever duller with each wash. Bleach is an option, but it ruins clothing.

Finally, we no longer hang out clothing in the sun to dry. The sun is the most effective and natural bleaching agent. Now a clothesline is considered tacky, so we don’t do that anymore. We stuff our clothes in a tumble dryer.

All of these changes have mounted gradually. The whites get ever duller. In a quarter century, we went from a country in which white cottons gleamed (and laundry doers beamed with pride) to one where most people are wearing dull shades of tan and gray. We think nothing of it. We don’t even know what we are missing.

There Is Hope

And yet there is a path forward, through the thicket of government regulations.

The first element is hot water. To get whites truly white, you need very hot water. I’ve learned to boil water in the largest pot I have, and then add that directly to the washing machine. There should be steam coming out of that water before you add your clothes.

You need to treat your whites with Spray and Wash or Shout, on the collars and cuffs, before they go into the wash, letting them sit for five minutes and sometimes rubbing them to loosen up the stains.

There is no clean laundry — and this goes for colors too — without using trisodium phosphate. Everyone serious about laundry knows this now. The purpose of this is to break down the soap and whisk it away in the water. This was banned by government regulations some 20 years ago, to the detriment of all laundry. The ostensible reason was to save the fish from excess algae growth in ponds, punishing domestic laundries rather than the real culprit, which is big agriculture.

As for the problem with drying clothes, I’ve mostly given up and acquiesced to the machine dryer instead of the glorious sun. Sometimes when I know for sure that no one will see, I will string a clothesline and let my whites experience a glorious natural bleaching. But the occasion rarely presents itself.

There Is More

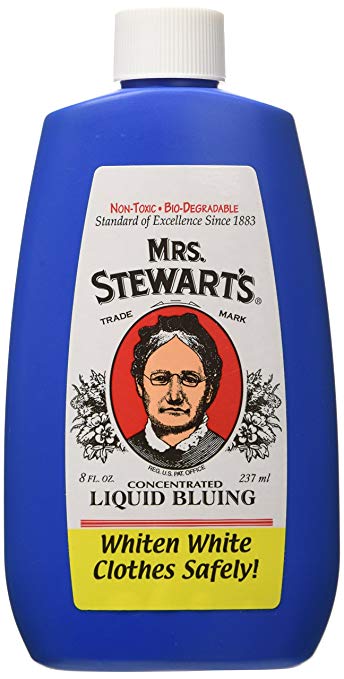

Sure enough, looking through Amazon, I found the magic liquid: Mrs. Stewart’s Bluing. This company, which is still family-owned, was established in 1883. It is a subtle blue dye. You mix a bit (just a few drops) in cold water and add it to your very hot water before adding your clothes. It adds just a hint of blue to your whites. You can’t see it. It depends on a bit of optical illusion by playing with the color spectrum: our eyes look at a tiny bit of blue and instead see white.

The story behind this project is truly inspiring. It was discovered at the very height of the gilded age when people began really to care about getting clothing bright white. If you think about it, white clothing signifies the rise out of the state of nature. Everything in nature is dirty, grungy, dull. To wear white illustrates the advance of society, the achievement of cleanliness, the triumph over dirt and muck. It’s a symbol because only in the late 19th century did this become possible for the masses of people.

The story of the bottle alone is fascinating. The old lady on the bottle was supposed to be the creator’s wife, but this person refused to pose. So he grabbed a picture of his mother-in-law and gave it to the artists. She was then immortalized. The company tried to modernize the picture in the 1970s, but consumers raged in revolt and the image reverted. Now the company itself sells tee shirts (probably the lamest tee shirt in history, which makes it all the more awesome).

Bluing your whites is the final touch, and probably won’t do the trick unless the other factors are in place.

Unlike in Bermuda, we don’t have a lot of white parties to attend. But knowing how to make clothes white is a skill of its own, a way of demonstrating that despite all government depredations, and the conspiracy to make our clothing boring, you possess the wherewithal to nonetheless rise above the state of nature and achieve something truly extraordinary.