Why Passive Management Wins Again

“No one hits .400 anymore because the average baseball player of today is far better than the average player of a hundred years ago.” (Swedroe and Berkin, The Incredible Shrinking Alpha)

In the early 20th century, professional baseball players batted over .400 four times in a 20-year span. Since Ted Williams’ magical 1941 season, no professional baseball player has batted .400. Although the aggregate professional batting average has remained stable at around .250, the variability of batting averages has declined as all players have become more skilled.

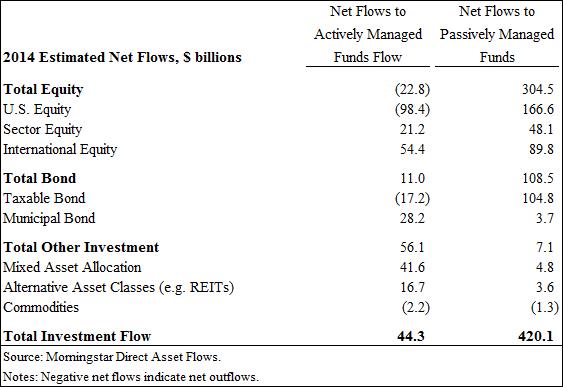

We can apply the same lesson to investing. It was a bad year for active managers, as less than one in five active U.S. equity funds outperformed their benchmarks in 2014. Many investors are realizing that they can pay less to invest directly in these benchmarks. According to Morningstar Direct, passive U.S. stock mutual funds pulled in $166.6 billion in 2014, while actively-managed U.S. stock mutual funds had net outflows of $98.4 billion (See table).

As investors move out of active portfolios, a theory has emerged that active managers will have a harder and harder time delivering alpha (returns above the benchmark). In a recently released book by Larry Swedroe and Andrew Berkin, The Incredible Shrinking Alpha, the authors posit that highly-educated experts that spend 60+ hours a week researching a handful of companies now have fewer amateurs to exploit as amateur investors move to passively managed funds. With fewer rubes to take the other side of their trades, generating excess returns may become more difficult than ever for active managers.

The field of money management has progressed much like professional baseball. In the 1920’s, Babe Ruth dominated inferior pitchers even as he smoked and drank excessively without ever hitting the weight room. The Paradox of Skill theory first described by Michael Mauboussin (The Success Equation: Untangling Skill and Luck in Business, Sports, and Investing) says that as fields attract higher levels of skill, luck becomes a more significant driver of unusual outcomes. Today’s hitters and pitchers are far more skilled and athletic than the professional ballplayers of the 1920’s, devoting countless hours of practice and training to their profession. Batting averages on aggregate are similar to the 1920’s, but the variation in batting averages has contracted as the overall level of skill has increased. This is why it has become nearly impossible for a professional baseball player to hit .400 today.

In money management, the relative skill of one super-smart expert over another super-smart expert is becoming razor thin, which therefore causes luck to become a larger share of potential outperformance. The bottom line is that there is less variability in outcomes and active managers as a group are becoming more homogenous.

When Boston College graduate Peter Lynch was making a name for himself with the Magellan fund in the early 1980’s, the spread between the best and worst money managers was large. Statistically speaking, the standard deviation of excess returns (“alpha”) was well over 10 percent. However, in recent years, the difference between the best and worst active managers has shrunk, with the standard deviation of excess returns closer to 6 percent (Mauboussin and Callahan, Alpha and the Paradox of Skill).

Delivering alpha is a zero-sum game writ large. When one manager outperforms his benchmark, someone else loses relative to the benchmark. On aggregate, active managers will therefore underperform passive managers after fees. While there will certainly be active managers that beat their benchmarks from time to time, predicting this outperformance in advance is becoming more difficult with the trend toward more standardized outcomes. In fact, in this area, research shows that past performance is a poor predictor of future performance. Luck has become a larger share of the equation, and luck is really hard to predict. This does not bode well for investors trying to identify outperformance in advance.

In the 1980’s, it was possible to find active managers who might predictably outperform their benchmark, like identifying a baseball player that might hit .400 in the 1920’s. Unfortunately, the level of competition today suggests that it is unlikely that any manager will bat .400 ever again.

This should only exacerbate the trend toward structured, passive strategies.