Why Do We Need So Many Monies?

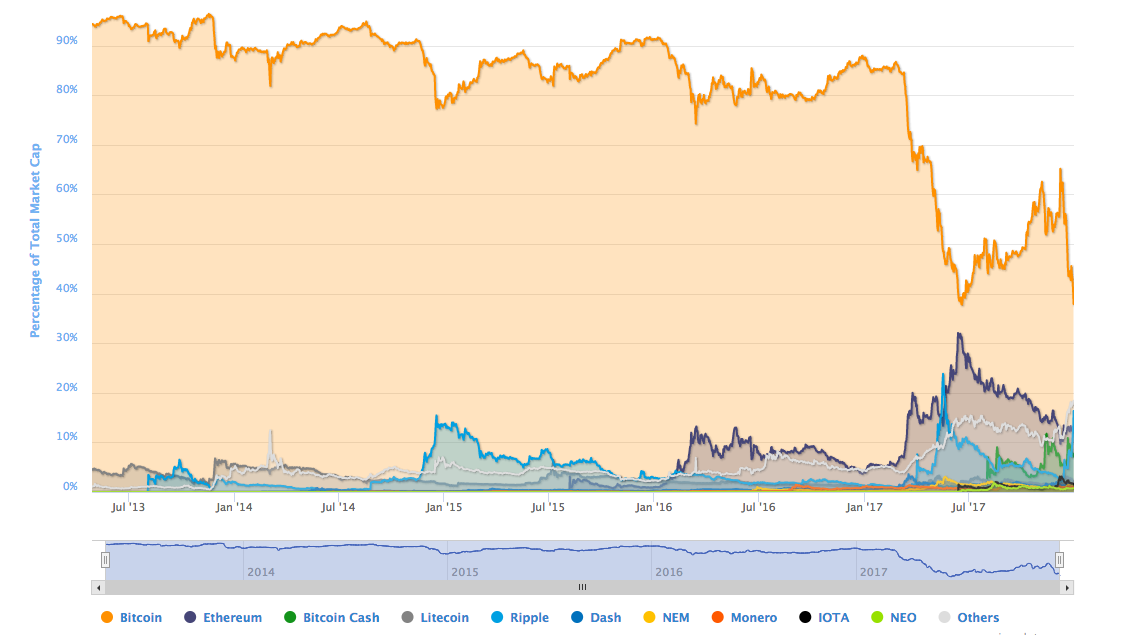

So many aspects of our newly competitive world of money defy prediction. For example, we wake this morning to observe that Bitcoin’s market dominance of the cryptoasset sector has fallen to 37%, from 90% five years ago. The great monopoly breaker itself has become subjected to some serious competition from other assets that use the same technology but offer different features. (The data set I’m using is skewed by the inclusion of Ripple, which has more in common with traditional payment systems than cryptocurrencies.)

The sector is becoming more diversified and rivalrous. King Bitcoin is facing a challenge the same way it pioneered as a competitor to national monies.

As for the alternatives, it’s been difficult to know ahead of time which of the tokens will take on a life of their own and which will fail. You might think that a community that has watched Bitcoin go from zero value to a high of $20,000 in nine years of existence would realize that no outside observer can know all, much less dictate outcomes.

Humility in this space comes at a premium. Still, when the August 2017 fork took place that created Bitcoin Cash (BCH) with a larger block size, the howling and screaming didn’t stop for months.

At some point, I sent a single tweeted suggestion that BCH might end up as a viable competitor to Bitcoin simply because Bitcoin had become so expensive to send and slow to transact. To me, this was no different from venturing a prediction about whether Coke or Pepsi would prevail in the market. Wrong. I can’t recall ever having been hit by so much vitriol as this one tweet elicited. Not even at the height of the political campaign had I seen such mania. It was like stepping in the largest red-ant hill on the playground.

And yet look today: BCH has been adopted in the wallets within most major exchanges. It is a preferred sending and receiving method among many people because it recalls the old days of Bitcoin, when fast and cheap were supposed to be main selling points of cryptocurrency over national money. You can have all the technical discussions you want over block-size limits. You can decry user behavior. You can denounce the exchange ratio. You can call anything you loathe a pump and dump. But what you cannot do is dictate or determine market outcomes with your biases.

Why So Many Deodorants?

A few years ago, Bernie Sanders uttered a passing comment that elicited howls of laughter among believers in competitive markets. “You don’t necessarily need a choice of 23 underarm spray deodorants or of 18 different pairs of sneakers when children are hungry in this country,” he said.

Rather than merely laughing at the statement, however, let’s consider the seriousness of what he was saying. It’s not automatically crazy. We know what deodorant is supposed to do: stop sweat and stink in a particular area of the body. We know what sneakers are supposed to do: protect the foot from external stress. Why, precisely, are there so many brands? You could say because we all want different scents and styles, and that’s true, but that doesn’t cover all the options. Maybe these products are the same in all essentials.

The intuition, then, is not entirely crazy. Why don’t consumers find the one brand that best fulfills the function at the best price and just make that the dominant one?

Why do we need this endless churning and upheaval and choice? Isn’t this endless competition between similar products socially wasteful?

This has been the case against competition for centuries. The perception is that it is basically inefficient. If we could magically take all the resources that go into getting people to switch from one brand to another, we could produce more of the canonical brand and save consumers and producers money. That’s not an intellectually preposterous idea.

For many decades, socialist central planners were persuaded by this kind of thinking. In a typical socialist grocery store in the old days, there was only one choice and they were named literally and without hype: beans, rice, coffee, sardines, bread, and so on. This was especially true with produce: tomatoes, bananas, and beets. Look at the efficiency! Look at the savings!

Why One Money?

You could say the same thing about money. We know what money is and does. Once we have it, we shouldn’t change it. We only need the dollar. We only need the Euro. We only need one cryptocurrency. Or perhaps we need to centrally plan who needs to use what currency, discerning through the magic of econometrics what constitutes an optimal currency area.

It’s true that we have now competition between existing national monies that operate within a defined government jurisdiction. What we do not have (for the most part) is competition between licit currencies within a country. Most Americans have never even considered money to be anything but the dollar. In other countries, the national money does compete with the dollar but mostly only in gray markets.

I can recall visiting Nicaragua at the height of socialist planning and encountering a huge black market for exchange rates between the national currency and the dollar. Kids as young as 12 were out on the streets making deals. They knew that tourists could get from them a better exchange rate than government exchanges. Tourists (even the socialist ones) love it. The math skills of these “child peasants” were better than most American college students.

But what about full-blown competition between currencies within countries? That is something that has been ruled out within all living memory. We’ve had socialism and monopoly provision for at least a century following the introduction of central banking.

Competition We Need

So let’s just explore some benefits that come from real competition in monetary units and services. The case is the same as it is for competition in every other good or service.

To have no barriers to entry invites many producers to compete for consumers’ affections. Rivals offer different features at different prices and invite the public to decide. This entails price reductions and quality improvements. This reduces producer profits over time but it also inspires innovation since any producer who can do better than the dominant player can win a higher rate of return and expand.

We can easily see this with, for example, pop stars. We need Taylor Swift, Mariah Carey, Justin Bieber, and Shawn Mendes, along with countless others, because each meets a different need, they learn from other, they get ever better through experimentation, and the process of competition here drives progress. There is also a healthy democratic element at work: which product, person, or service provider becomes dominant truly is the people’s choice.

We do not know precisely what “pop music” is in its archetypal form, certainly not enough to codify it and legislate it. We understand that we need an unending process of discovery and creativity because it is music. But the same applies to every service or product. There is always a better way to mow your lawn, vacuum your carpet, or dry clean your clothes. There is always a better and cheaper coffee, mattress, or mouse trap.

A Better Money

And there’s always a better way to do money. Realizing this is perhaps the greatest intellectual contribution that Bitcoin has made to the world. It has shown us new possibilities that most people – to say nothing of monetary economists – had not thought about. The usual historical trajectory of money starts with stones, shells, pelts. It moves to precious metals. Then it culminates in fiat paper managed by the central bank. Surely we have seen the best, the apotheosis of monetary perfection.

Bitcoin came along with some new propositions. How about a money and payment system in a single package? How about we get really strict about ownership claims and make these public, and enforce them not by trust but by proof? How about the system regulate the rate of creation of new units according to a public protocol rather than relying on the discretion of industry-connected insiders? How about a system of storage that is controlled by owners rather than third parties?

Ten years ago, most of this would have seemed impossible but now we know that it is not. We’ve come to realize that money as a technology should be listed among the practical arts, something to be improved and evolved through a market-based process of competition and entrepreneurship.

Among many huge problems with fiat-money central banking is that it stops the process of discovering new and better ways. It presumes that we know all we need to know. You could say the same about those who think there ought to be only one cryptocurrency and it should be Bitcoin. We can’t actually say this. CoinMarketCap lists 1,372 cryptocurrencies. You can add a couple of zeros there and approximate how many exist today.

They offer different features, mining methods, and levels of privacy. Some are purely brands. There is nothing wrong with that. How many should there be? That is not for any intellectual much less central planner to decide. That is for the market to decide, same as with deodorant and shoes. At last we see that money is a product and a service that need ever stop evolving to better serve human needs.