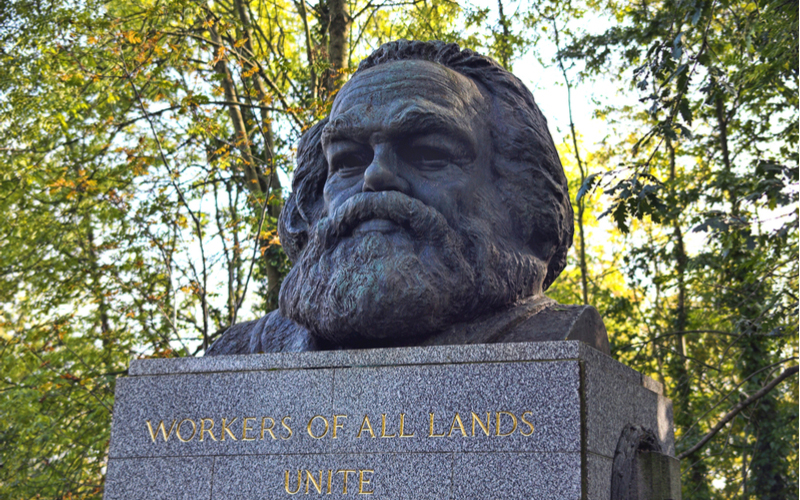

Who Can Claim Credit for the Karl Marx Monument?

Over the weekend, vandals attacked a monument to Karl Marx near his grave in London’s Highgate Cemetery. It was the second such attack in less than a month. While the first attempted to deface the inscription with hammer strikes, the more recent attack painted a new inscription of its own reading “Memorial to Bolshevik Holocaust: 1917-1953, 66,000,000 Dead.”

The most recent attack sparked immediate outrage, particularly from journalist and academic admirers of Marx. Several took to social media to denounce the vandalism as “despicable.” More than a few suggested it was inappropriate to link the monument to the Bolsheviks, seeing as Marx died several decades before Lenin came along. A common defense of Marx holds that the Soviet Union was not “real communism,” thereby allowing the German philosopher off the hook for its human toll.

Granted, acts of vandalism — even against controversial historic monuments — are a defective strategy for political protest, even when the followers of the memorialized subject expressly disavow the concept of property rights. Setting that aside though, the vandals actually have a stronger historical claim behind their message. The Marx monument in Highgate Cemetery is in fact intimately and inextricably linked to the Bolshevik and Soviet derivative of Marxism.

The History of the London Marx Monument

Specifically, the Marx statue that was defaced is not original to the location. In fact, it does not even sit atop Marx’s original gravesite. Marx died in 1883 and was buried under a simple marker next to his wife, who predeceased him.

The current memorial traces its origins to much later events, all of which are closely connected to the Bolshevik movement in Russia. That story begins when V.I. Lenin instigated a split between his followers (the Bolsheviks) and his rival Julius Martov (derisively dubbed the Mensheviks) at the Second Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party in Brussels, Belgium, in 1903. As a result of the split, Lenin and his followers convened their own breakaway meeting in London that July. The conference concluded with a visit by Lenin to Marx’s gravesite, where various Bolshevik leaders proclaimed honorifics to their hero. Bolshevik pilgrimages to the grave became a recurring activity from then until Lenin seized power in Russia in 1917.

Despite these visitations, Marx’s grave sat in a state of neglect. Lenin personally responded in 1918 by directing Soviet diplomats to offer 1,000,000 rubles to finance the construction of a new monument to Marx at the site. The offer never found a taker, but for the next 30 years Marx’s grave continued to serve as a pilgrimage site whenever high-ranking Soviet officials visited London.

Russian diplomats ensured annual commemorations continued at the grave. Stalin’s loyal protégé Vyacheslav Molotov even held a wreath-laying ceremony there in 1947. During the same period, the Soviet government also unsuccessfully attempted to secure exhumation rights to the grave, with plans to relocate Marx and his family to Moscow, where they could be placed near Lenin under an extravagant monument.

None of the exhumation plans came to fruition because of squabbling among Marx’s descendants as well as British reluctance to entertain such a blatant Cold War–era propaganda move. In 1954, however, the British government granted two of Marx’s grandchildren permission to reinter the Marx family at a more visible plot about 100 yards from its original location.

This relocation, taking place over 70 years after Marx’s death, finally cleared the way for the construction of the current monument. The large bronze bust of Marx that we see today was finally unveiled in 1956 at a ceremony attended by Soviet diplomats as well as representatives from Maoist China and the governments of most of the Eastern Bloc. The Communist Party of Great Britain paid for the monument, designed by one of its members Laurence Bradshaw. Party chair Harry Pollitt, who oversaw the entire project and presided over the dedication ceremony, was an avowed supporter of hardline Stalinism and had been working as a covert agent of the Soviet government since the 1930s.

Adding Context to the Monuments Debate

The history of the 1956 Marx statue presents an interesting conundrum for defenders of the monument and historians in general. While Marx’s followers are now eager to dissociate his legacy from the murderous regimes of Lenin and Stalin, the Soviet connections to this monument are extensive and undeniable. The effort to secure the monument was a personal project of Lenin himself, and the eventual construction only came about after decades of direct support and diplomatic pressure from the Soviet government.

Controversial monuments, and especially those linked to historical injustices, have come under intense scrutiny in recent years. While some of these monuments coincide with military commemorations of Civil War battles, others have been linked to the long history of racial violence in the United States. That latter link is increasingly becoming the main criterion that historians rely upon while recommending a course of action for a disputed statue.

In 2017, for example, the city of New Orleans removed a monument to an 1874 white-supremacist uprising intended to suppress African American voters. Similarly instructive is the ongoing saga over the “Silent Sam” statue at the University of North Carolina. This monument was dedicated to students of the university who lost their lives in the Civil War; however, extensive archival research also revealed that the dedication ceremony in 1913 featured an overtly white-supremacist speech by its primary donor, UNC trustee Julian Carr. The statue was pulled down by vandals in August 2018, and its fate is currently undetermined as university officials debate whether to restore, relocate, or remove it on account of this racially tainted origin.

Gravesite monuments are by no means exempt from these considerations. In late 2017, the city of Memphis removed an equestrian statue of Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest that also sat atop his grave. Much like the Marx monument, it was not original to Forrest’s grave. It dated to 1901, when Forrest — also a founder of the Ku Klux Klan — was disinterred from his 1877 burial location and relocated to a more prominent space. The Forrest statue is currently the subject of an intense legal battle between the city of Memphis, Confederate heritage organizations, and Forrest’s descendants.

While the larger Confederate statue debate carries many complexities and intense disagreements that fall beyond the scope of the present discussion, it strongly suggests that historians have settled upon an important general principle for evaluating controversial statuary: the history of the statue’s construction matters as much as the statue’s own subject when measuring its purposes and ethical dimensions, including events that happened decades after the subject’s death.

That being the case, the Marx monument in London cannot escape its deep ties to Bolshevism, to Lenin and Stalin, to Mao, and to the Soviet incarnation of Marx’s philosophy. Those ideas and figures were directly responsible for its construction, some 73 years after Marx’s death. Their legacies are therefore indelibly imprinted upon the large bronze bust that sits atop the plinth next to Marx’s grave.

While I offer no specific advice on what should be done with the Marx memorial, its supporters have an ethical obligation to reconcile their defense of the statue with its explicit historical connections to Soviet dictators and associated atrocities. That could entail removal in place of restoration. But it could also warrant the addition of contextual markers, documenting past Soviet commemorations at the site and the monument’s direct connections to one of the 20th century’s most brutal regimes.

Simply avoiding the ugly complications of this Soviet legacy, however, is no longer an option. If the standards applied to evaluate other controversial monuments have any meaning at all, consistency dictates the dubious historical legacy of Bolshevism must be part of any discussion about the future of Marx’s monument in London’s Highgate Cemetery.