When will Federal Debt Become THE Question?

It was getting late and the group, which had gathered to hear and discuss my presentation on America’s economic outlook over dinner, was ready to head home. Among other topics, I had referred to federal government debt as the elephant in the room. I had also said that the elephant was not trumpeting as yet, but that the day would come when we would hear from it.

To make the point, I had focused on the interest cost of the debt. In 2018, even with interest rates low, it hit an imposing $324 billion. All the rest of government that year excluding Social Security, health care, and defense had run $391 billion. Clearly, something will have to give — and give it may.

Change could happen for a combination of two reasons: more debt and higher interest rates. Our leaders have shown little resolve to scale back the debt. But more immediately, higher interest costs would force a political budget squeeze. Congress would be forced either to reduce spending on Social Security benefits, health care, defense, or that “other government” category. Those higher interest costs are surely on the way, though probably not in 2019 or 2020.

The program chair indicated time for one last question, and immediately a hand went in the air. “Thank you for tonight’s presentation,” the gentleman said, “but I want to push back a bit on your discussion of debt and Social Security.”

He went on to say that he had been hearing scary things about federal debt and Social Security all his life, but that somehow things always seemed to work out. He then asked the hard question: “Why are things different now?” As he spoke, I thought about the story of the boy who cried wolf.

I attempted to explain why things are different, pointing out the rapid growth in government debt since 2008 and the current push for even more deficit financing. I reiterated that we are not yet in crisis mode, but that politically tough times were headed our way unless we cut back on our addiction to debt finance.

As the meeting ended, I wondered if I’d differentiated myself from all those other boys shouting wolf.

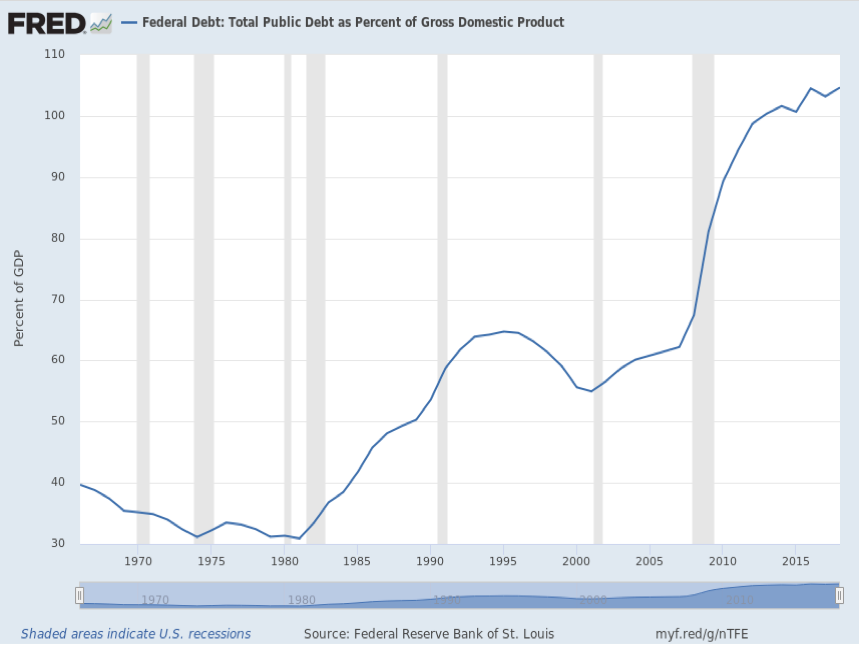

Unfortunately, I had not been armed with the Federal Reserve Bank chart showing total public debt as a percentage of GDP. Maybe if I had been so equipped, my story would have been more convincing.

Look closely at the chart and you will see that from 1965 through the early 1980s, government debt stood at no more than 40 percent of GDP. It rose after that until the mid-1990s, hitting 65 percent of GDP. Growth then relaxed until the start of the Great Recession in 2008. From 2008 to 2018, the share rose from roughly 70 percent to 110 percent. Of course, we do not pay interest on percentage points, but each of the chart’s percentage points represents a larger amount of debt to be financed.

Here’s the point: The amount of public debt to be serviced is huge and growing, and we’re in uncharted territory now. The challenge we faced in funding our debt in the 1970s and 1980s was nothing like what we face now. We can also see that the debt problems faced in one decade were often resolved by simply borrowing more. All the while, the services we Americans demanded from government grew apace. Social Security, health care, and defense together took a growing part of the U.S. budget.

So now, it seems, we can see difficult times ahead. Unless we restrain ourselves, debt interest costs will take a larger bite of GDP and federal revenue. Something will have to give. Just as the gentlemen with the last question suggested, I doubt that Congress will abruptly cut Social Security benefits. But if things continue unchanged, Congress will cut something. Defaulting on the debt, with all the extra borrowing costs that would bring, is not an option.