When Financial Markets Bubble, There’s Something for Everyone

Thomas Levenson of MIT has written a timely book: Money For Nothing: The South Sea Bubble and the Invention of Modern Capitalism. As many assets on the world’s financial markets rise and rise and rise, and many pundits call for an inevitable collapse that never seems to arrive, looking at bubbles of the past provides the very perspective that financial historians are good at.

Whenever something seems bubbly, accusations of tulips and South Sea bubbles are never far away – even though the proportion of people who could actually explain those iconic episodes of our financial past is frighteningly close to zero.

Writing on the South Sea bubble three hundred years after the events of 1720 is a pretty brave endeavor. Plenty of books have expertly dealt with the topic in the last half-century or so: John Carswell’s The South Sea Bubble, Richard Dale’s The First Crash, relevant chapters in Peter Temin and Hans-Joachim Voth’s Prometheus Shackled, The Great Mirror of Folly, edited by William Goetzmann and others just to name a few. In the professional journals dedicated to our economic and financial past, even more has been written: The Economic History Review devoted a full issue last year to reprinting some of the most important research on the South Sea Bubble from the last thirty years.

Levenson skillfully steers clear of the intricate financial analysis that frequent much of that work. He makes the financial mechanisms involved easily accessible for the non-expert, and brings a fairly novel angle to the bubble: literary references. Daniel Defoe’s witty words are everywhere; Archibald Hutcheson’s merciless financial dissection is a great addition; Isaac Newton’s givings and misgivings bring both clarity and human context. The personal stories of Robert Walpole and the Whig-Tory party politics of the 1710s make the story less about financial mania and more about corruption and political power grabs. A nice niche that brings new life to the South Sea era.

We get the deep political and institutional background stretching from the Glorious Revolution in 1688 and the illustrating story of the fascinating coffee shops that turned Exchange Alley into a place for financial trading. We follow Newton’s mathematical struggles with the properties of a curve, his early days escaping the plague-ridden Cambridge in the 1660s, his appointment to the Royal Mint in 1696 and his decades-long work at the center of England’s (and after 1707 the United Kingdom’s) monetary world.

As a story of the South Sea Bubble all of this feels a bit odd: a good hundred pages elapses before the main attraction makes an entrance – the establishment of the South Sea Company (SSC) in 1711. Not entirely unlike today, Britain’s public finances were in disastrous shape. One difference is that today’s mountain of debt is easily serviced at record-low interest rates, whereas the British government’s debts in the 1710s were unbearably expensive and could not be retired for decades even with peacetime budget surpluses.

The SSC, initially set up to do trade with Spanish America, had successfully consolidated some of the government’s outstanding debt in previous schemes, thereby turning illiquid and non-standardized government annuities into South Sea stock. Many accounts of the South Sea Bubble jump straight into the mania, implying willfully that investors and financial markets suddenly went mad for no good reason. Perhaps so, but there was something to the SSC that made plenty of people believe its prospects.

Levenson painstakingly explores the value-add in allowing holders of questionable long-dated government annuities to exchange them for liquid instruments with a daily price in Exchange Alley: “Creditors became owners,” writes Levenson, “exchanging the promise of regular payments on their money for a stake in a new hopefully profit-making concern.” Since the first such swap in the 1710s would be at par – £100 of South Sea stock for £100 of government debt – even though scant annuities in Exchange Alley traded at a discount, it was a great bargain for those holding government debt.

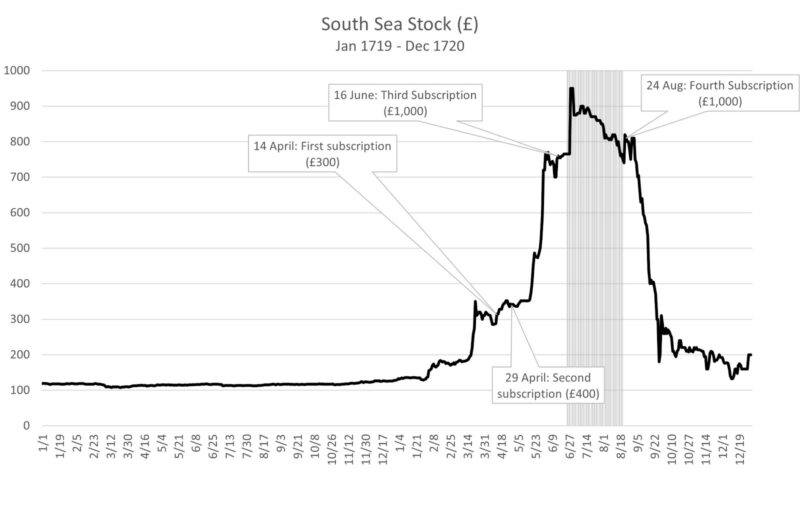

The success of the first few rounds is reflected in the altogether boring share price all the way up to January 1720:

After the SSC directors and schemers had successfully finished a few rounds of this cleaning-up of government finances, their hubris took over. In early 1720 they petitioned Parliament for their most ambitious scheme yet: converting all of Britain’s outstanding debt into shares in this corporate leviathan. This was the beginning of heavy lobbying, crookedness, insider trader and outright bribery. One example is the separate ledger of fictitious shares issued to Members of Parliament that didn’t require them to put up any money, but if the market share price rose would yield them handy profits, handed out by insiders.

In Parliamentary negotiations, the “moneyed” companies (SSC, Bank of England, and East India Company) started bidding generously for the privilege of receiving government interest payments, a fight that the SSC finally won with a promise of a one-time gift to the government of £7.6 million – almost 10% of GDP and as much as one-seventh of the floating government debt.

As the debates took place in the House of Commons and counterproposals were submitted by the other companies, the SSC share price exploded – from the mediocre £110-£120 range it had hovered at before the start of the year to £135 when the proposal was first presented to Parliament on January 22, 1720 and £184 in mid-February; it passed £200 in March and £300 the week before the final bill was approved by Parliament.

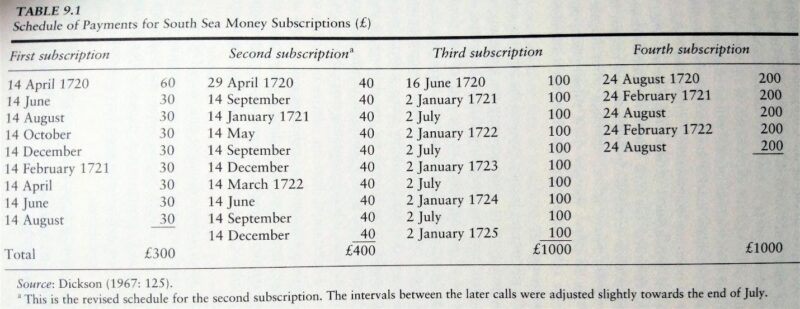

To finance this gigantic takeover of government debt, the SSC issued new shares in four subscription rounds. The first was oversubscribed, issued in April at £300 when the market price was £315, for an instant 5% profit – dwindling compared to the double-digit or triple-digit first-day returns we’ve seen in recent years. The second round, only two weeks later, was offered at £400 with a more lax payment plan:

When the precise terms for the debt swap (how much the company would pay for a given amount of government debt) were announced on May 19, the shares jumped 30% in a few days and rallied to the vertiginous price of £720 on June 1 – a 460% return in five months (Bitcoin, anyone? Tesla?). The third and fourth subscriptions, in mid-June and late-August respectively, were offered at £1,000 and had no trouble selling; the subscription list even included Sir Isaac Newton himself.

During the summer, the steam propelling the SSC ran out. The financial engineering they had pulled off worked by swapping new shares at market prices but accounting for them at par: redeeming £1,200 worth of government bond when the SSC stock traded at £400 only required 3 shares to satisfy, leaving a neat 9 shares in the Company coffers to sell for revenue or advance as bribes (£1,200/100 = 12 shares created, only 3 of which were given to debt-holders to extinguish their claim on the government).

In the summer, the company directors grew increasingly desperate in their attempts to keep the stock price high, as the scheme would come crashing down as soon as the new inflow of funds on Exchange Alley was no longer enough to maintain it. They had Parliament pass the “Bubble Act” in June that prohibited new stock companies; they announced a generous dividend and closed the transfer books for two months to process it; they purchased stock with company funds to keep up the price – but it was all for naught. Until September or so the stock hovered around £800 before it plunged to £200 in little over a month, a level where it would remain until it was reorganized by parliament in the following years.

While a fascinating story of mania and corruption, Levenson’s book is quite a sprawling read. Its lengthy American subtitle – The Scientists, Fraudsters, and Corrupt Politicians Who Reinvented Money, Panicked a Nation, and Made the World Rich – makes a prospective reader even more confused. Let’s take the claims in turn.

The only scientist really connected to the South Sea Bubble is Isaac Newton: first as the Master of the Royal Mint, where his suggestions for how to solve the lack of silver coins – an overvalued exchange rate on the bimetallic standard caused coins to be clipped, melted, and exported – were overruled. Secondly, he successfully rode the South Sea stock’s rally in the spring, sold out, and made a fortune. He then got cold feet and plunged his earnings back at the peak before he lost what he had made. Other scientists make an appearance in Levenson’s book, but mostly for their contributions to mathematical problems of parabolas and what we’d today call discounted cash flows. While those ideas took center stage in the spring of 1720, it’s not clear how the scientists themselves were involved with the mania.

Some of the key players in the bubble were the Fraudsters who pushed the scheme and bribed politicians, and the Corrupt Politicians who unscrupulously traded with what we’d today refer to as “insider traders” – in addition to their creative accounting and stock manipulation.

It’s not clear that the South Sea Bubble “Panicked a Nation” unless Levenson is using ‘panic’ as a synonym for financial Mania, and it’s highly doubtful that anything in the South Sea story “Made the World Rich.” The “Invention of Capitalism” in the British subtitle is similarly odd as the emergence of capitalist markets were fairly detached from the dealings of London in 1720 – if anything, the South Sea debacle delayed mature capital markets by prohibiting joint-stock companies in Britain until 1826.

Contrary to the misused Tulipmania, this bubbling scheme in 1720 did involve large swathes of the English population, vividly described by literary accounts from people like Daniel Defoe and Jonathan Swift. In contrast to its French counterpart under John Law in the year before, it was not accompanied by a money-printing government bank. Nuance matters.

I think the main reason that the South Sea Bubble lives on in popular (and professional) memory three centuries on is that there’s something for everyone. We have discovery and use of new financial technology. We have the early trials and successes of public finance. We have a stock going to the moon before it suddenly collapses. We have “retail” investors dabbling in assets and markets they know next-to-nothing about. We have crooked insiders, and perhaps the first grand government bailout. And we have plenty of ammunition for both sides of the “rationality of financial markets” debate – all wrapped in plenty of literary accounts and detailed price movements.

Do any of those topics ring a bell for the financial markets of today?

Levenson’s account of the South Sea Bubble will not, I daresay, be the last time historians find reason to look at this grand event of our financial past.